Roadmap

Our Roadmap is as follows:

- Our thesis is that Scripture nowhere encourages or commands Christians of any kind to interpret the Scriptures on their own, meaning, in such a way that should they differ with other Christians (lay or ordained), and licitly separate from them based on this interpretation. We will show this through an Introduction explaining my background, and how I came to realize this Scriptural truth that was deeply inconvenient for my protestantism, followed by two parts. Part 1 will address the authority of the Apostles themselves, and several other matters, including:

- The common protestant argument from the Bereans (Acts 17:10-13);

- The case of the Ethiopian Eunuch (Acts 8:26-40);

- The normative authority and fellowship of the Apostles (Acts 2:42);

- The case of St. Matthias, the Apostle; and

- The case of St. Paul, the Apostle.

- Part 2 will show that the authority of the Apostles to teach was already being exercised and passed down by other leaders they were appointing by briefly examining:

- The example of the Ephesian presbyters (Acts 20:28);

- St. Paul’s teaching on authority in his letters to St. Timothy;

- St. Paul’s teaching on authority in his letter to St. Titus;

- The apparent apostolic co-authorship of Scripture, illustrating the passing down of apostolic authority;

- The commands to obey leaders in Scripture;

- The apostolic warning to not interpret Scripture on your own; and

- The Council of Jerusalem (which is covered in much more detail in Becoming Catholic #12); we will then

- Summarize the conclusions we believe are justified by the foregoing scriptural evidence.

Introduction

Now that I am Catholic, I recognize many steps along my journey that, at the time, I didn’t realize were leading me to the Catholic Church.

One of those steps was in my early college years (perhaps between the ages of 18-20) when I realized there was not a single example in Scripture of individual Christians presuming to interpret the Bible on their own apart from the Apostles, or those they had appointed as leaders. Indeed, the Apostles themselves never began interpreting Scripture apart from one another, splitting in different directions based on their varying interpretations.

This realization greatly disturbed me. While I had been part of various protestant sects, and ultimately ended up in a Reformed Presbyterian congregation a few years before beginning my exploration of the Church Fathers, the belief was roughly the same in all of them: we as individual believers may interpret the Scriptures as best as we possibly can. Many claimed the “Holy Spirit” was guiding them. Others would certainly rely heavily on protestant creedal and confessional statements. But at the end of the day, most of us protestants believed that if we, as individuals, concluded in good conscience that Scripture meant X, and whatever denomination taught Y, we would leave that denomination, and either go to another that taught X (or was closer to it), or we’d begin our own. While perhaps not preferred by all, this was seen as normal and to a very high degree acceptable among protestants of many different sects.

Additionally, I was disturbed by the fact that there was so much doctrinal disagreement to begin with. I realized the furthest I could get, even assuming I was hearing the opinions of men who were in good faith, educated, and virtuous, was a good guess. As I have explained elsewhere, I wanted to follow Jesus, who said that if we love Him, we will obey His commandments. But upon realizing so many around me were fundamentally disagreeing about what those commandments were, I realized my desire to love Christ was hitting a roadblock. I simply couldn’t know which of them was correct.

That was when, as a Bible-loving protestant, I decided to study the Bible to see if I could discover how such doctrinal disputes were supposed to be solved, and who had authority to teach.

That’s when I came to a disturbing discovery: I could find absolutely nothing like what we protestants were doing in the very Scriptures we all claimed to be basing our faith on.

Indeed, what I was seeing among late 20th and early 21st century American protestants did not reflect the views of many 16th century protestant “reformers,” most of whom had a high view of “church authority.” But despite these views, they themselves had broken from ecclesial authority based on alternative interpretations of Scripture. Thus, they were hardly in a position to claim others could not do the same (though they often did just this, at least in those days).

That is precisely why protestantism has been endlessly dividing over differing interpretations of Scripture from the beginning. As many protestant confessions explicitly assert, Scripture alone has infallible authority. No office occupied by a human being can claim to speak with God’s authority on its meaning. Only Scripture can speak with God’s authority.

Therefore, the natural conclusion is that if a Christian believes Scripture teaches X, while a human authority teaches Y, they are obligated to go with what “Scripture” says. This of course assumes they are correct in their interpretation—but untangling that issue is for another day. The point here is that even for protestant sects with a higher view of “church authority,” this logic is unavoidable.

Not all the congregations I attended had the exact same view. The Presbyterian congregation, for example, had a higher view of church authority than, say, many of the non-denominational congregations (though I attended some of those that I later discovered were little more than dictatorial personality cults).

But at the end of the day, even the very traditional Presbyterian congregation would assert that if I differed in how I interpreted Scripture from them, I had every right, as a Christian, to go where I believed Scripture was being interpreted with the greatest fidelity. In principle, while believing their doctrine was “best,” they would not object to me or others founding our own “church” based on an alternative interpretation, so long as it generally fell within what they considered a broad range of “essentials” (the incoherence of this position will likewise be addressed elsewhere).

But as I realized in college, this model that was everywhere normative, and considered “orthodox” Christianity among protestants, was nowhere to be seen in the one place I was always taught to go for ultimate guidance in the Christian life: Scripture. This was ironic, because virtually all of us claimed to be “Bible Christians.”

Pursuing this realization to its logical conclusion over the ensuing decade ultimately led me to the Catholic Church.

But what I realized even in those earlier days was that Scripture showed an entirely different model than what I knew as a protestant: in the Church described in the Bible, doctrine was never authoritatively interpreted by individual lay Christians, but only by apostolic authority—the Apostles, and the leaders they appointed. Outside this line of authority, I couldn’t find a single example of a Christian being commanded or commended for interpreting Scripture on their own, or even with a group of others.

Among those leaders themselves, I could not find a single example of one of them going off on their own, apart from the rest, based on their own interpretation of Scripture. On the contrary, the only individuals who arrogated this authority to themselves were heretics and schismatics, who St. John identifies with the spirit of Antichrist (1 John 2:18-19):

18 Children, it is the last hour; and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come; therefore we know that it is the last hour. 19 They went out from us, but they were not of us; for if they had been of us, they would have continued with us; but they went out, that it might be plain that they all are not of us.

PART 1: The Bereans, the Ethiopian Eunuch, and Apostolic Authority and Communion

The Bereans (Acts 17:10-13)

Probably the most common protestant argument in favor of their model is the Bereans. Since the Bereans, they claim, examined the Scriptures to see if what St. Paul was saying was true, we are likewise justified in examining the Scriptures to see if what ecclesial authorities are saying is true.

But a careful reading of the story shows it is actually detrimental to the protestant position.

The account reads as follows (Acts 17:10-13):

10 The brethren immediately sent Paul and Silas away by night to Beroea; and when they arrived they went into the Jewish synagogue. 11 Now these Jews were more noble than those in Thessalonica, for they received the word with all eagerness, examining the scriptures daily to see if these things were so. 12 Many of them therefore believed, with not a few Greek women of high standing as well as men. 13 But when the Jews of Thessalonica learned that the word of God was proclaimed by Paul at Beroea also, they came there too, stirring up and inciting the crowds.

The key line often used by protestants is verse 11: “they received the word with all eagerness, examining the scriptures daily to see if these things were so.” This, it is claimed, justifies individual believers interpreting Scripture on their own, and if need be separating into various denominations based on said interpretations.

But the Bereans did not interpret Scripture on their own. They understood it only after being taught to interpret it properly by the Apostle Paul (vv. 10, 13). Undoubtedly, he would have done something similar to what Jesus did in the synagogue in Nazareth: he read the scrolls of sacred Scripture, and then interpreted them to those in the gathering (see Luke 4:16-30). In any event, the Bereans, like the Nazarites, never arrived at the truth of Christ with just themselves and their Bible. It had to be authoritatively pronounced and interpreted to them. And once this was done, they did not separate from St. Paul and the other believers. On the contrary, they joined them, and came under apostolic authority, recognizing that Paul had been sent by God to preach the Gospel.

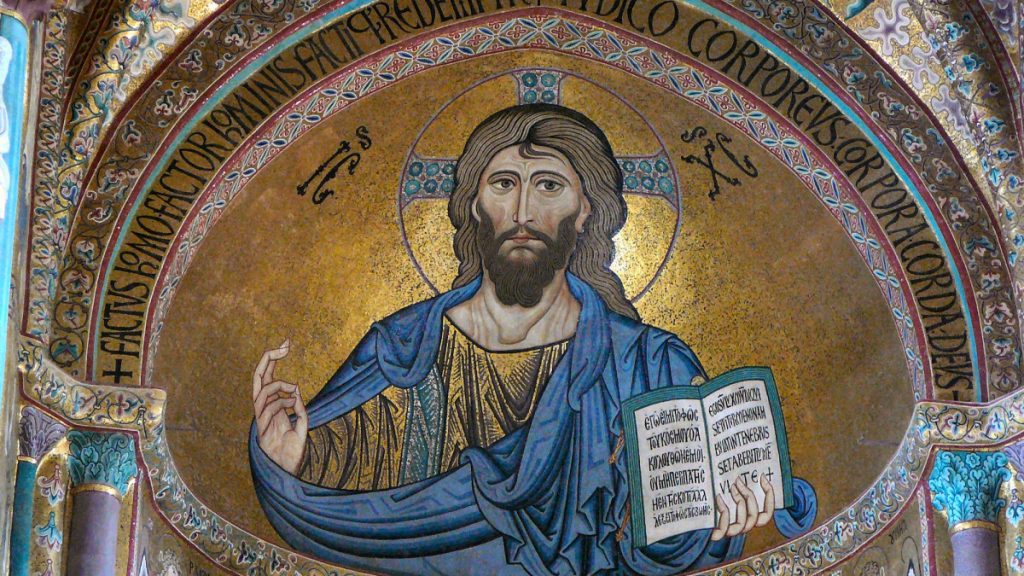

Once they heard the apostolic proclamation, and were taught directly by St. Paul how it made sense of Scripture, only then did they see the truth, and no doubt through the gift of faith given by God Himself. Our Lord Himself did the same thing multiple times with both the Pharisees and the disciples, such as on the road to Emmaus after His Resurrection (Luke 24:27):

And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.

Far from being an example of Christians interpreting Scripture on their own such that they are empowered to divide into separate denominations, the case of the Bereans exemplifies the exact opposite: the necessity of apostolic authority to properly interpret Scripture in the first place. Through the gift of faith, those who hear the message can perceive and assent to the truth of it. But they are not arriving at this truth by themselves.

Moreover, the Bereans in question were not even Christians when they did the very thing protestants point to as justification for their model. They were Jews and pagans. Thus, as a friend of mine observed, “You can’t use the example of people outside the Church to demonstrate how authority works within the Church.”

Thus, the Berean example so often appealed to by protestants simply doesn’t work. Who can blame the Bereans for examining the Scriptures to see if what St. Paul was saying was true? Of course they would—as should all believers. To hear the Messiah had come, and to understand how the Law and the Prophets had been fulfilled, would be an incredibly exciting prospect in and of itself.

I did the same when I was a young protestant Christian—and I do the exact same thing today as a Catholic. I study what the Church teaches, and how its magisterial pronouncements, doctors, and saints have unpacked the Scriptures on each particular point. It’s an exciting, edifying process—and in no way suggests my independence from established ecclesial authority. Rather, it is how I deepen my understanding of what is being taught.

The Bereans did the exact same thing.

Having realized that this (arguably) strongest of protestant arguments was in fact nothing of the sort, I continued my study of Scripture to see if our protestant model was there. If Christians can interpret Scripture on their own, and if Scripture is the sole infallible rule of faith, then surely there must be examples in Scripture of what we “Bible Christians” did, right?

I discovered the exact opposite was true.

In short, I could not find a single example of individual believers ever interpreting Scripture on their own. On the contrary, they always and everywhere—like the Bereans—did so under the guidance of apostolic authority, namely an Apostle, or someone appointed by them.

Here are some examples.

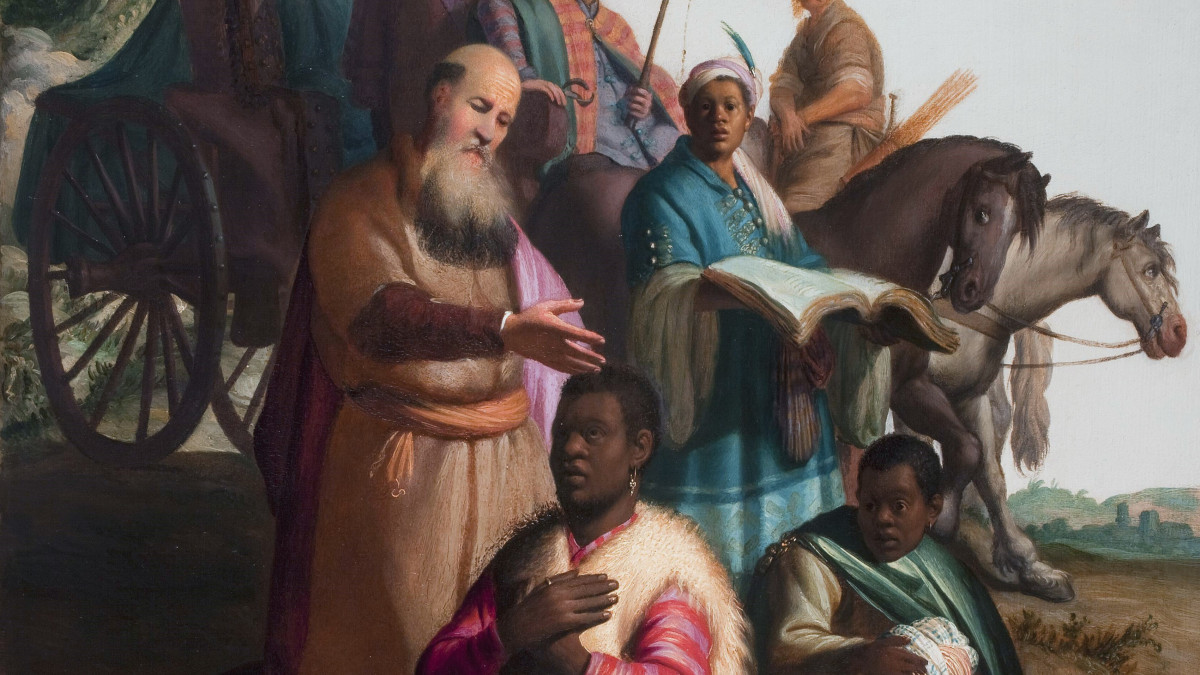

The Ethiopian Eunuch (Acts 8:26-40)

In the book of Acts, an Ethiopian eunuch is returning home from worshipping at the Temple in Jerusalem. Along the way, he reads the book of Isaiah. God sends him Philip, who asks him, “Do you understand what you are reading?” (Acts 8:30). With great humility, the eunuch responds, “How can I, unless someone guides me?” and then invited Philip to sit with him (v. 31).

They read Isaiah 53:7-8, which speaks of a sheep being led to slaughter. The eunuch asks Philip, “‘About whom, pray, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someone else?’ Then Philip opened his mouth, and beginning with this scripture he told him the good news of Jesus” (vv. 34-35). The eunuch was convinced, and decided to be baptized.

Of particular note is that the eunuch is not an intellectual simpleton. Scripture informs us that he was “a minister of the Candace, the queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of all her treasure” (v. 27). That, and the fact that he could read in an age of widespread illiteracy, tell us he was an educated man. And yet, even this man, who was returning from worshipping at the Jerusalem Temple (and thus likely somewhat knowledgeable of the Torah) acknowledges his need for a teacher to understand Scripture. God provided it, and his sins were cleansed in baptism.

The Authority and Fellowship of the Apostles (Acts 2:42)

From the earliest days of the Church, it was clear to new converts that becoming a Christian entailed submitting to visible apostolic authority. The book of Acts, for example, says the following of the very first converts (Acts 2:42):

42 And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.

This is everywhere the norm in the New Testament, many of the books of which were authoritative precisely because they were authored by Apostles, and/or men they had approved.

But we also see the nature of this authority by the way in which Apostles after the original twelve were appointed, particularly St. Matthias and St. Paul.

St. Matthias: An Apostle Chosen by Apostles

Let’s first briefly examine the appointment of Matthias as an Apostle. We need not go into every detail of this appointment as an Apostle and its implications. A few salient points will suffice. We read (Acts 1:20, 23-26):

20 For it is written in the book of Psalms,

‘Let his habitation become desolate,

and let there be no one to live in it’;

and

‘His office let another take’ (Ps. 109:8)…

And they put forward two, Joseph called Barsabbas, who was surnamed Justus, and Matthias. 24 And they prayed and said, “Lord, who knowest the hearts of all men, show which one of these two thou hast chosen 25 to take the place in this ministry and apostleship from which Judas turned aside, to go to his own place.” 26 And they cast lots for them, and the lot fell on Matthias; and he was enrolled with the eleven apostles.

The essential point here is this: the Apostles were appointed by Christ to teach the nations the Gospel. It was they who had authority to interpret Scripture. But St. Matthias, in becoming an Apostle, did not choose himself. He was chosen by God, through the instrumentality of the Apostles, the visible leaders of the Church.

While there was no doctrinal point at question here, I include this example to show that the leadership of the biblical Church, which had been appointed as authoritative teachers by Christ Himself, was the organ by which other leaders were invited to partake in that same authority. This would necessarily limit those who may rightly interpret Scripture (i.e. teach doctrine) to leaders so appointed. There are many more examples of this throughout the New Testament, both large and small. One of the more important ones involves another Apostle, St. Paul.

St. Paul: An Apostle Under Authority

While we can’t cover every detail of St. Paul and his ministry here, it is sufficient to note that at every point, Our Lord uses Him in and with the one visible Church.

For example, after his dramatic encounter with the Risen Lord on the road to Damascus, Saul (as he was then named in the Bible) is not directly commissioned by Christ at this time, but directed to go to Damascus, where he will be told what to do by others (Acts 9:3-6):

3 Now as he journeyed he approached Damascus, and suddenly a light from heaven flashed about him. 4 And he fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” 5 And he said, “Who are you, Lord?” And he said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting; 6 but rise and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.”

Saul then arrives in Damascus. At this point, Our Lord told a man named Ananias in a vision that he must go to Saul, and lay hands on him so that his sight could be restored. Ananias was naturally skeptical, given Saul’s persecution of the Church. Then Our Lord declares Saul’s mission for the first time—but not to Saul himself, rather to Ananias (Acts 9:15-16):

15 But the Lord said to him, “Go, for he is a chosen instrument of mine to carry my name before the Gentiles and kings and the sons of Israel; 16 for I will show him how much he must suffer for the sake of my name.”

Saul then meets Ananias, and through him, his sight is restored, he receives the Holy Spirit, and he is baptized. Saul then began proclaiming Jesus to be the Son of God in the local synagogues (vv. 19-22). At this point, there is no evidence he was doing what he would later do as a fully established Apostle, namely found churches wherever he went. He was preaching and attempting to convince his fellow Jews of the faith—a behavior exemplified by many zealous converts—but he was not establishing churches. He remained in Damascus for an unspecified length of “many days,” after which he escaped in a basket upon hearing there were Jews who were plotting to kill him (vv. 23-25).

It was at this point in St. Luke’s history in the book of Acts that he says St. Paul came back to Jerusalem, where the small community of believers was obviously afraid of him, for he had previously persecuted the Church. Barnabas, however, took him to the Apostles, after which he lived freely among the Christians in Jerusalem, suggesting that this new freedom among the believers of the Mother Church was the result of apostolic approbation and acceptance of his testimony (Acts 9:27-29):

27 But Barnabas took him, and brought him to the apostles, and declared to them how on the road he had seen the Lord, who spoke to him, and how at Damascus he had preached boldly in the name of Jesus. 28 So he went in and out among them at Jerusalem, 29 preaching boldly in the name of the Lord. And he spoke and disputed against the Hellenists…

St. Paul himself provides us several more details about his “many days” in Damascus, as well as his time in Jerusalem, in his letter to the Galatians. Concerning what he did during his “many days” in Damascus, he wrote (Gal. 1:15-17):

15 But when he who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, 16 was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with flesh and blood, 17 nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me, but I went away into Arabia; and again I returned to Damascus.

We thus see that his “many days” in Damascus also included a sojourn in Arabia. No details are provided on what he did there. After this likewise unspecified period of time, he returned to Damasus. It is at this point, as St. Luke recounts, that Paul went to Jerusalem, which he describes as follows (Gal. 1:18-24):

18 Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas, and remained with him fifteen days. 19 But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother. 20 (In what I am writing to you, before God, I do not lie!) 21 Then I went into the regions of Syria and Cilicia. 22 And I was still not known by sight to the churches of Christ in Judea; 23 they only heard it said, “He who once persecuted us is now preaching the faith he once tried to destroy.” 24 And they glorified God because of me.

Again, we see that Paul is received by “the churches of Christ in Judea” after he spent time with the Apostles in Jerusalem, particularly St. Peter, or “Cephas,” meaning “Rock” (see Matt. 16:18).

St. Paul then gives us more details about a later trip to Jerusalem which he ascribes to “revelation.” The purpose of this trip, in his own words, was to place the Gospel he had preached before the Apostles “lest somehow I should be running or had run in vain.” Thus, in Paul’s mind, the Apostles in Jerusalem could have done one of two things: they could have confirmed the Gospel he preached, or denied it. He says that their decision had bearing on whether he was “running” (present tense) or “had run” (past tense) in vain (Gal. 2:1-2):

Then after fourteen years I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas, taking Titus along with me. 2 I went up by revelation; and I laid before them (but privately before those who were of repute) the gospel which I preach among the Gentiles, lest somehow I should be running or had run in vain.

He then tells us of their decision (Gal. 2:6, 7-10):

6 And from those who were reputed to be something… 7 …when they saw that I had been entrusted with the gospel to the uncircumcised, just as Peter had been entrusted with the gospel to the circumcised 8 (for he who worked through Peter for the mission to the circumcised worked through me also for the Gentiles), 9 and when they perceived the grace that was given to me, James and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised; 10 only they would have us remember the poor, which very thing I was eager to do.

St. Paul identifies St. James, Cephas (St. Peter), and St. John as the “pillars” of the Church, and asserts they did indeed confirm his Gospel, and extend him “the right hand of fellowship.” In doing so, they confirmed Paul’s calling to preach the Gospel among the Gentiles, while they would focus on the Jews. We know this wasn’t a permanent bifurcation of duties, not only because Scripture frequently describes Paul preaching to Jews, but because St. Peter later speaks to the rest of the Apostles at the Council of Jerusalem about the fact that “in the early days God made choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe” (Acts 15:7).

In any event, God’s election of St. Paul to preach to the Gentiles was confirmed by the authority of Christ’s Apostles. Once more, God authoritatively worked through the visible apostolic structure Christ had originally established.

These events leading up to St. Paul’s establishment as an Apostle were especially significant for me as a protestant who was reading the Bible to discern how doctrinal disputes should be handled. The reasons why were because at each step of the way, St. Paul was told by Christ Himself, or others in the Church, to approach members and leaders of the visible Church, and at various points he received the approval and confirmation of both himself and his Gospel by the visible apostolic leadership of the Church.

St. Paul, of all men, would have a plausible claim to go off on his own and preach whatever he believed had been revealed to him by Christ. But he nowhere does that, nor does Christ ever tell him to do so.

On the contrary, St. Paul goes to visible members of the Church for healing and baptism (Ananias), goes to the visible leaders of the Church in order to operate freely among believers (the Apostles on his first journey back to Jerusalem), and finally receives confirmation of his doctrine and his commission to preach to the Gentiles from the same visible apostolic leadership of the Church (the Apostles on his second journey back to Jerusalem), a visible leadership he himself joined as he describes in his letter to the Galatians.

This was nothing like the protestant model in which men so often appoint themselves (as they did in the 16th century), and presume to divide in every which direction, all claiming “Scripture” as their authority.

But the authority of the Apostles with respect to teaching doctrine was not restricted to the Apostles alone. While the Apostles are the foundation of the Church, and had unique authority, Scripture shows us multiple examples in which some portion of their authority was already being exercised and seemingly passed down to other leaders they appointed. Individual believers were, in turn, commanded to obey these leaders as well.

PART 2: The Passing Down of Apostolic Authority

Not only were believers in the biblical Church under the authority of the Apostles, they were also under the authority of those appointed by the Apostles. This can be shown by numerous examples.

The Ephesian Presbyters (Acts 20:28)

One such example would be the manner in which St. Paul addresses the presbyters of the church in Ephesus (Acts 20:28):

28 Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you guardians, to feed the church of the Lord which he obtained with his own blood.

Thus, while he appointed these presbyters, St. Paul equates this appointment with being appointed directly by God, which—as we will see later—necessarily leads to the conclusion that they and other leaders so appointed should be obeyed.

St. Timothy

St. Paul’s letters to St. Timothy and St. Titus are particularly revealing when it comes to where authority to teach and interpret Scripture resides.

We’ll begin with his first letter to Timothy. At the very beginning, Paul is clear that he has given Timothy an authoritative charge (1 Tim. 1:3, 18-19):

3 As I urged you when I was going to Macedonia, remain at Ephesus that you may charge certain persons not to teach any different doctrine…18 This charge I commit to you, Timothy, my son, in accordance with the prophetic utterances which pointed to you, that inspired by them you may wage the good warfare, 19 holding faith and a good conscience.

As St. Paul had appointed leaders with authority to teach and govern in the churches himself (Acts 14:23), he now lays this responsibility on Timothy. He is explicit that this includes the authority to correct false doctrine.

The Apostle then provides a series of instructions on doctrine, and the qualifications of bishops and deacons. “If you put these instructions before the brethren, you will be a good minister of Christ Jesus, nourished on the words of the faith and of the good doctrine which you have followed,” (1 Tim. 4:6) he says to Timothy. The Apostle is again clear that Timothy possesses authority to teach (1 Tim. 4:11-16):

11 Command and teach these things. 12 Let no one despise your youth, but set the believers an example in speech and conduct, in love, in faith, in purity. 13 Till I come, attend to the public reading of scripture, to preaching, to teaching. 14 Do not neglect the gift you have, which was given you by prophetic utterance when the elders laid their hands upon you. 15 Practice these duties, devote yourself to them, so that all may see your progress. 16 Take heed to yourself and to your teaching; hold to that, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers.

Likewise, Timothy has authority over the other presbyters (1 Tim. 5:17):

17 Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching…

As for those who would contradict this doctrine and Timothy’s authority, the Apostle is likewise clear (1 Tim. 6:2-5, 20):

Teach and urge these duties. 3 If anyone teaches otherwise and does not agree with the sound words of our Lord Jesus Christ and the teaching which accords with godliness, 4 he is puffed up with conceit, he knows nothing; he has a morbid craving for controversy and for disputes about words, which produce envy, dissension, slander, base suspicions, 5 and wrangling among men who are depraved in mind and bereft of the truth, imagining that godliness is a means of gain…20 O Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to you. Avoid the godless chatter and contradictions of what is falsely called knowledge, 21 for by professing it some have missed the mark as regards the faith.

Similar affirmations are made in St. Paul’s second letter to Timothy, which repeat his original charge of appointing leaders who will have the authority to teach (2 Tim. 2:1-2):

You then, my son, be strong in the grace that is in Christ Jesus, 2 and what you have heard from me before many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also.

Timothy—not individual, non-appointed believers—is tasked with rightly handling the truth (2 Tim. 2:15):

15 Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a workman who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth.

In the next several verses, St. Paul specifies the names of two heretics who are contradicting the Faith on the resurrection (vv. 16-18). With respect to these and other dissenters, the Apostle once again affirms Timothy’s authority, and ascribes such dissent to the devil (2 Tim. 2:24-26):

24 And the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kindly to everyone, an apt teacher, forbearing, 25 correcting his opponents with gentleness. God may perhaps grant that they will repent and come to know the truth, 26 and they may escape from the snare of the devil, after being captured by him to do his will.

With these considerations in mind, the Apostle lays a solemn charge on Timothy (2 Tim. 4:1-4):

I charge you in the presence of God and of Christ Jesus who is to judge the living and the dead, and by his appearing and his kingdom: 2 preach the word, be urgent in season and out of season, convince, rebuke, and exhort, be unfailing in patience and in teaching. 3 For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own likings, 4 and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander into myths.

Once again, this authority belongs to Timothy, not to every believer. It is he who has the authority to teach doctrine, appoint leaders, etc. in the local church over which St. Paul has placed him. No one else.

St. Titus

St. Paul’s letter to St. Titus is very similar. If anything, he uses even stronger language about Titus’s authority.

At the beginning, as he had done with Timothy in Ephesus, he charges Titus with appointing presbyters in Crete (Tit. 1:5):

5 This is why I left you in Crete, that you might amend what was defective, and appoint elders in every town as I directed you…

The Apostle is clear that only those presbyters appointed by Titus will have the authority to teach, and must therefore “hold firm to the sure word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to confute those who contradict it” (Tit. 1:9). Note that this authority to teach includes the authority to silence dissenters. St. Paul is clear that those who have not been appointed by Titus do not have authority to teach, and in fact must be silenced (Tit. 1:10-11):

10 For there are many insubordinate men, empty talkers and deceivers, especially the circumcision party; 11 they must be silenced, since they are upsetting whole families by teaching for base gain what they have no right to teach.

“But as for you,” he says, “teach what befits sound doctrine” (Tit. 2:1). He leaves no room for doubt that at least in Crete, this authority belongs to Titus, and Titus alone (Tit. 2:15):

15 Declare these things; exhort and reprove with all authority. Let no one disregard you.

He again repeats that this authority must be exercised against heretics who would contradict Titus (Tit. 3:10-11):

10 As for a man who is factious [hairetikos], after admonishing him once or twice, have nothing more to do with him, 11 knowing that such a person is perverted and sinful; he is self-condemned.

Thus, it is clear that Titus is being invested with an authority similar to St. Paul’s, and the Apostle is tasking him with doing precisely what he was doing in his various letters. Such authority comes from God—first given to St. Paul by God, and from Paul to Titus, just as with Timothy.

Apostolic Co-Authorship of Scripture

Another interesting angle to consider is the fact that several letters of Scripture, while written primarily by an Apostle, nonetheless includes non-Apostles in their salutations, i.e. the section where the author of the letter is identified. In doing such, it is as if the Apostle’s words are also those of such leaders, and they are at least partially identified with the Apostle in their authority. I am not asserting that we can make definitive claims based on this observation. The argument is not dispositive. But it is at least interesting, given the numerous delegations of authority by the Apostles to others throughout the New Testament, and the multiple times other people are included in the salutations of apostolic letters, namely 1-2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians, and 1-2 Thessalonians.

For example, St. Paul opens his first letter to the Corinthians as follows (1 Cor. 1:1-2):

Paul, called by the will of God to be an apostle of Christ Jesus, and our brother Sosthenes,

2 To the church of God which is at Corinth…

This Sosthenes is quite possibly the Sosthenes mentioned in the book of Acts as being the former leader of the Corinthian synagogue (Acts 18:17):

17 And they all seized Sosthenes, the ruler of the synagogue, and beat him in front of the tribunal.

Thus, Sosthenes could very well have been an early convert through hearing St. Paul’s preaching. The fact that the Apostle includes him as an apparent “co-author” implies that he is being identified with the Apostle and his authority. Indeed, one of the earliest Church historians, Eusebius of Caesarea, notes that many believed Sosthenes was one of the seventy disciples appointed by Christ, and affirmed that he “wrote to the Corinthians with Paul…”1

St. Paul writes a similar salutation in his second letter to the Corinthians, but this time includes Timothy (2 Cor. 1:1):

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and Timothy our brother.

To the church of God which is at Corinth, with all the saints who are in the whole of Achaia…

A more generalized salutation is given in the letter to the Galatians (Gal. 1:1-2):

Paul an apostle—not from men nor through man, but through Jesus Christ and God the Father, who raised him from the dead—2 and all the brethren who are with me,

To the churches of Galatia…

The letter to the Philippians includes Timothy as a “co-author” (Phil. 1:1):

Paul and Timothy, servants of Christ Jesus,

To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are at Philippi, with the bishops and deacons…

Likewise, in the letter to the Colossians (Col. 1:1-2):

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and Timothy our brother,

2 To the saints and faithful brethren in Christ at Colossae…

The first letter to the Thessalonians includes two “co-authors” along with Paul (1 Thess. 1:1):

Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy,

To the church of the Thessalonians…

The same “co-authors” are identified in the second letter to the Thessalonians. (2 Thess. 1:1)

Paul also includes Timothy in his letter to Philemon (Philem. 1:1):

Paul, a prisoner for Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother,

To Philemon our beloved fellow worker…

Thus, the self-evident authority of the Apostles, alongside the authority of those they appointed as leaders in the churches, is supported by the fact that on multiple occasions, St. Paul includes these leaders as apparent “co-authors” of his letters. For what purpose was this done by the Apostle, or by the God who was speaking through him, if not to in some way identity the authority of the co-author with the (human) author, and thereby imply a passing down of authority?

Commands to Obey Leaders

Scripture also contains several blanket admonitions to obey not only the Apostle (which was implicit), but the leaders they appointed.

For example, St. Paul writes as follows in his first letter to the Thessalonians (1 Thess. 5:12-13):

12 But we beseech you, brethren, to respect those who labor among you and are over you in the Lord and admonish you, 13 and to esteem them very highly in love because of their work. Be at peace among yourselves.

Likewise, in his second letter to the same church, whose salutation listed Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy, he wrote (2 Thess. 2:15):

15 So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter.

And again (2 Thess. 3:14):

If anyone refuses to obey what we say in this letter, note that man, and have nothing to do with him, that he may be ashamed.

Similarly, the author of the book of Hebrews gives the same command (Heb. 13:17):

17 Obey your leaders and submit to them; for they are keeping watch over your souls, as men who will have to give account. Let them do this joyfully, and not sadly, for that would be of no advantage to you.

Thus, the Apostles assume a divinely established authority structure with which their readers are familiar. This authority structure not only included the Apostles themselves, but those they had appointed (and presumably, those they had told them to appoint as well). There is zero indication that any Christian can appoint themselves outside this line of authority.

Apostolic Warning: Don’t Interpret Scripture On Your Own

Far from encouraging believers to simply interpret the Bible on their own, Scripture explicitly warns against it.

St. Peter, for example, says the following (2 Pet. 1:20-21):

20 First of all you must understand this, that no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation, 21 because no prophecy ever came by the impulse of man, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God.

Since all Scripture is God-breathed, this necessarily means that the proper understanding of it cannot be, as St. Peter says, “a matter of one’s own interpretation.” This would take what was revealed by God and obscure it by that which only comes from individual men. In other words, there is no such thing as a binding understanding of Scripture that comes from one’s private interpretation. While St. Peter does not say so explicitly, the implication is that the proper interpretation of Scripture is public, and thus issues from public authority (i.e. the Apostles and those ordained by them). We will briefly discuss the preeminent example of this—the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15—in the next and final section.

St. Peter also warns that Scripture can be difficult to understand, and that this has caused those who interpret it apart from apostolic authority to fall into error (2 Pet. 3:15-17):

So also our beloved brother Paul wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, 16 speaking of this as he does in all his letters. There are some things in them hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other scriptures. 17 You therefore, beloved, knowing this beforehand, beware lest you be carried away with the error of lawless men and lose your own stability.

Likewise, St. Jude specifically warns believers to not disobey authority, which can only be a reference to the authority of the Apostles, and those they have ordained, as we have already seen (Jude 1:8-11):

8 Yet in like manner these men in their dreamings defile the flesh, reject authority, and revile the glorious ones…10 But these men revile whatever they do not understand, and by those things that they know by instinct as irrational animals do, they are destroyed. 11 Woe to them! For they walk in the way of Cain, and abandon themselves for the sake of gain to Balaam’s error, and perish in Korah’s rebellion.

This understanding of St. Jude’s admonition is reinforced by considering one of the specific examples he cites, namely “Korah’s rebellion.” This refers to a rebellion against Moses and the Levitical priesthood (Numbers 16), who were entrusted with the law and its interpretation (Deuteronomy 17, et al). The rebels—Korah, Dathan, and Abiram—made a very protestant argument that all Israelites were equal, and seemed to deny the very existence of the ministerial priesthood of the Levites under the High Priest, Aaron (Num. 16:3):

[T]hey assembled themselves together against Moses and against Aaron, and said to them, “You have gone too far! For all the congregation are holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them; why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?”

God commanded Moses, Aaron, and the Israelites with them to separate from the rebels, who were presuming to approach the tabernacle and offer sacrifices to God. They were ultimately swallowed up by the earth, and those who presumed to offer incense to God were consumed by fire (Num. 16:31-35).

It is this paradigm St. Jude offered as a warning to New Covenant Christians to not “reject authority.” Once more, it was clear that individual Christians outside the apostolic line of authority had no right to interpret Scripture apart from their ordained leaders. This simply didn’t make sense within my protestant framework.

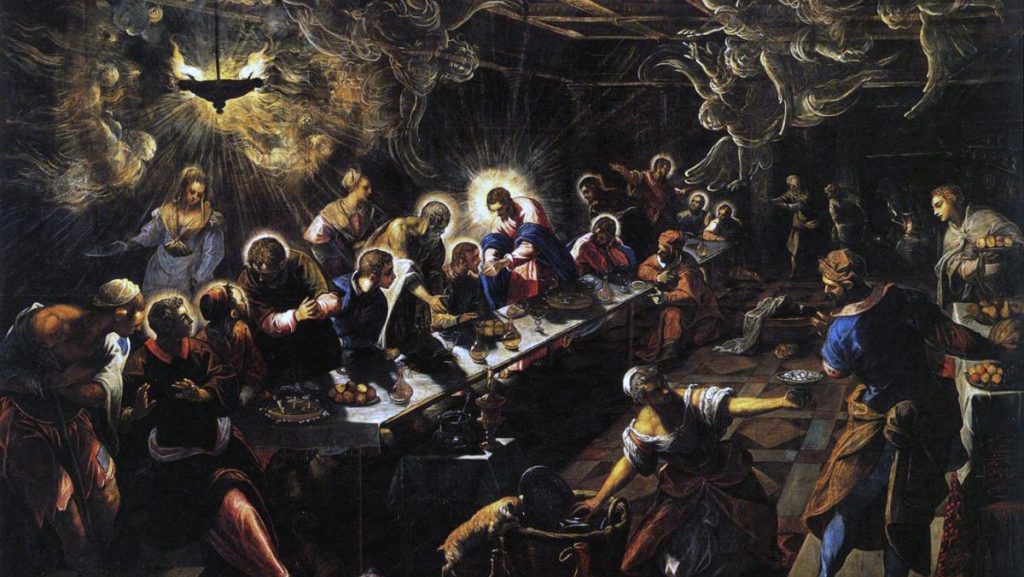

The Council of Jerusalem

Finally, perhaps the preeminent example in the New Testament of apostolic authority on doctrine comes from the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15. I have written at great length about this event, and how it played an important role in my becoming Catholic. (See Becoming Catholic #12: Why Acts 15 Led Me to the Catholic Church)

Three brief points will suffice here.

First, the Council consisted of not only Apostles, but presbyters appointed by them (Acts. 15:6). Judgment belonged to them, not laymen, not ordinary believers. This is an important point, for when the Council renders a decision, it is rendered by both Apostles and non-Apostles, showing that there is an authority that is being both passed down, and jointly exercised.

Second, the Council spoke with God’s authority and its own: “For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us…” (Acts 15:28) A divine judgment was rendered through the agency of men—not believers reading Scripture on their own.

Third, the Council’s decision was binding on the entire Church, as Scripture explicitly states (Acts 16:4):

As they [Paul, Barnabas, etc.] went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and presbyters who were at Jerusalem.

There was no local church autonomy here, as was commonly taught in many of the protestant sects of which I was a part, or knew of.

Thus, when a controversy arose in the biblical Church, it rendered a judgment with the authority of God by the agency of men, namely the Apostles and those they had appointed. It was these men—not lay believers—who had authority to teach doctrine and interpret Scripture. And despite the fact that there was initially some disagreement, all submitted to the final decision, which was believed to have been reached with God’s authority.

Conclusion

The Catholic Church encourages Her children to read the Scriptures, and gives many inducements to do just that. However, they are always and everywhere required to do so under the very same guidance given to the Bereans, the Ethiopian Eunuch, and all the early Christians: apostolic authority.

As a protestant who was confused and frustrated by the amount of doctrinal disagreement among protestant sects, I studied the Scriptures to discern what they taught about how doctrinal disputes are to be handled.

Far from seeing the model I was everywhere witnessing and told was “biblical,” I found something quite different, and very much at odds with the protestant paradigm.

The only reasonable conclusion I could reach was summed up by the title of this entry: “No one in Scripture interpreted it on their own.”

Instead, they were under the authority of leaders who claimed, and indeed on occasion exercised, infallible authority to bring theological disputes to an end. No protestant sect made such a claim of authority, despite the fact that they all claimed to follow the Bible.

As a protestant, after analyzing the Bible to learn what it taught about how to handle theological disputes, all I could think was, “We don’t have a church that can do this.”