(Updated May 28, 2025)

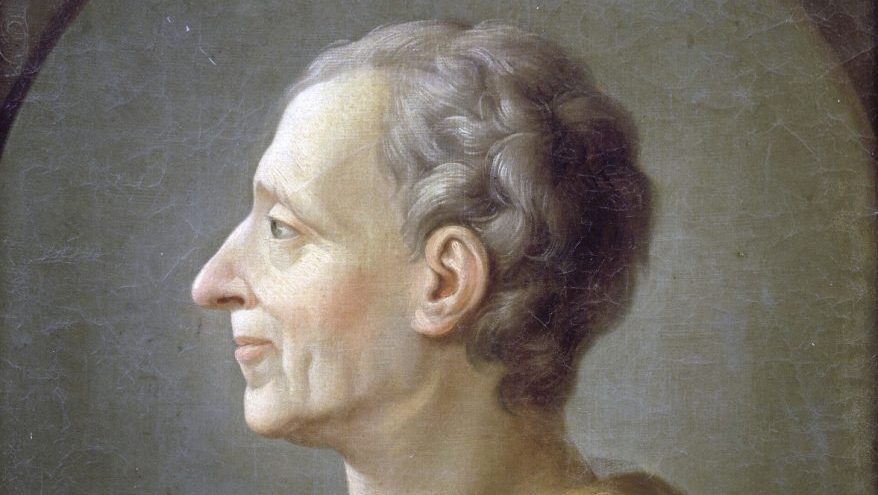

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1689-1755) was a French political philosopher, judge, and historian. His writings were widely read by the American Founders.

The Spirit of the Laws (1748)

Part 1, Book 3, Chapter 3: On the principle of democracy1

There need not be much integrity for a monarchical or despotic government to maintain or sustain itself. The force of the laws in the one and the prince’s ever-raised arm in the other can rule or contain the whole. But in a popular state there must be an additional spring, which is virtue.

What I say is confirmed by the entire body of history and is quite in conformity with the nature of things… For it is clear that less virtue is needed in a monarchy, where the one who sees to the execution of the laws judges himself above the laws, than in a popular government, where the one who sees to the execution of the laws feels that he is subject to them himself and that he will bear their weight.

It is also clear that the monarch who ceases to see to the execution of the laws, through bad counsel or negligence, may easily repair the damage; he has only to change his counsel or correct his own negligence. But in a popular government when the laws have ceased to be executed, as this can come only from the corruption of the republic, the state is already lost…

The political men of Greece who lived under popular government recognized no other force to sustain it than virtue. Those of today speak 22 | 23 to us only of manufacturing, commerce, finance, wealth, and even luxury.

When that virtue ceases, ambition enters those hearts that can admit it, and avarice enters them all. Desires change their objects: that which one used to love, one loves no longer. One was free under the laws, one wants to be free against them. Each citizen is like a slave who has escaped from his master’s house. What was a maxim is now called severity; what was a rule is now called constraint; what was vigilance is now called fear. There, frugality, not the desire to possess, is avarice. Formerly the goods of individuals made up the public treasury; the public treasure has now become the patrimony of individuals. The republic is a cast-off husk, and its strength is no more than the power of a few citizens and the license of all.

Part 3, Book 14, Chapter 11: On the laws relating to diseases from the climate2

As it is in the wisdom of legislators to keep watch over the health of the citizens, it would have been very sensible to check the spread of the disease by laws made on the plan of the Mosaic laws.

Part 3, Book 15, Chapter 5: On the slavery of Negroes3

It is impossible for us to assume that these people [slaves] are men because if we assumed they were men one would begin to believe that we ourselves were not Christians.

Part 5, Book 25, Ch. 1: On the feeling for religion4

The pious man and the atheist always speak of religion; the one speaks of what he loves and the other of what he fears.

Part 5, Book 25, Chapter 3: On temples5

The laws of Moses were very wise. Those who murdered involuntarily were innocent, but they had to be removed from the sight of the relatives of the deceased; therefore, Moses established an asylum for them [Num. 35:14]. The greatest criminals did not merit any asylum; they had none [Num. 35:16-21]. The Jews had only a portable tabernacle, which changed its place continually; this excluded the idea of asylum. It is true that they were to have a temple, but the criminals, who would have come there from everywhere, could have disturbed the divine service. If the murderers had been driven out of the country, as they were by the Greeks, it would have been feared that they would worship foreign gods. All these considerations led to the establishment of towns of asylum where one had to remain until the death of the high priest.

Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and Their Decline (1748)

Chapter 9: Two Causes of Rome’s Ruin6

When the domination of Rome was limited to Italy, the republic could easily maintain itself…Since the number of troops was not excessive, care was taken to admit into the militia only people who had enough property to have an interest in preserving the city. Finally, the senate was able to observe the conduct of the generals and removed any thought they might have of violating their duty.

But when the legions crossed the Alps and the sea, the warriors, who had to be left in the countries they were subjugating for the duration of several campaigns, gradually lost their citizen spirit. And the generals, who disposed of armies and kingdoms, sensed their own strength and could obey no longer.

The soldiers then began to recognize no one but their general, to base all their hopes on him, and to feel more remote from the city. They were no longer the soldiers of the republic but those of Sulla, Marius, Pompey, and Caesar. Rome could no longer know if the man at the head of an army in a province was its general or its enemy.

As long as the people of Rome were corrupted only by their tribunes, to whom they could grant only their own power, the senate could easily defend itself because it acted with constancy, whereas the populace always went from 91 | 92 extreme ardor to extreme weakness. But, hen the people could give their favorites a formidable authority abroad, all the wisdom of the senate became useless, and the republic was lost.

What makes free states last a shorter time than others is that both the misfortunes and the successes they encounter almost always cause them to lose their freedom. In a state where the people are held in subjection, however, successes and misfortunes alike confirm their servitude. A wise republic should hazard nothing that exposes it to either good or bad fortune. The only good to which it should aspire is the perpetuation of its condition.

If the greatness of the empire ruined the republic, the greatness of the city ruined it no less.

Rome had subjugated the whole world with the help of the peoples of Italy, to whom it had at different times given various privileges [but not citizenship]…But when this right [to citizenship] meant universal sovereignty, and a man was nothing in the world if he was not a Roman citizen and everything if he was, the peoples of Italy resolved to perish or become Romans…Forced to fight against those who were, so to speak, the hands with which it enslaved the world, Rome was lost. It was going to be reduced to its walls; it therefore accorded the coveted right of citizenship to the allies who had not yet ceased being loyal, and gradually to all.

After this, Rome was no longer a city whose people had but a single spirit, a single love of liberty, a single hatred 92 | 93 of tyranny—a city where the jealousy of the senate’s power and the prerogatives of the great, always mixed with respect, was only a love of equality. Once the people of Italy became its citizens, each city brought to Rome its genius, its particular interests, and its dependence on some great protector. The distracted city no longer formed a complete whole. And since citizens were such only by a kind of fiction, since they no longer had the same magistrates, the same walls, the same gods, the same temples, and the same graves, they no longer saw Rome with the same eyes, no longer had the same love of country, and Roman sentiments were no more.

The ambitious brought entire cities and nations to Rome to disturb the voting or get themselves elected. The assemblies were veritable conspiracies; a band of seditious men was called a comitia.7 The people’s authority, their laws and even the people themselves became chimerical things, and the anarchy was such that it was no longer possible to know whether the people had or had not adopted an ordinance.

We hear in the authors only of the dissensions that ruined Rome, without seeing that these dissensions were necessary to it, that they had always been there and always had to be. It was the greatness of the republic that caused all the trouble and changed popular tumults into civil wars. There had to be dissensions in Rome, for warriors who were so proud, so audacious, so terrible abroad could not be very moderate at home. To ask for men in a free state who are bold in war and timid in peace is to wish the impossible. And, as a general rule, whenever we see everyone tranquil in a state that calls itself a republic, we can be sure that liberty does not exist there.

What is called union in a body politic is a very equivocal thing. The true kind is a union of harmony, whereby all the 93 | 94 parts, however opposed they may appear, cooperate for the general good of society—as dissonances in music cooperate in producing overall concord. In a state where we seem to see nothing but commotion there can be union—that is, a harmony resulting in happiness, which alone is true peace. It is as with the parts of the universe, eternally linked together by the action fo some and the reaction of others.

But, in the concord of Asiatic despotism—that is, of all government which is not moderate—there is always real dissension. The worker, the soldier, the lawyer, the magistrate, the noble are joined only inasmuch as some oppress the others without resistance. And, if we see any union there, it is not citizens who are united but dead bodies buried one next to the other.

It is true that the laws of Rome became powerless to govern the republic. But it is a matter of common observation that good laws, which have made a small republic grow large, become a burden to it when it is enlarged. For they were such that their natural effect was to create a great people, not to govern it.

There is a considerable difference between good laws and expedient laws—between those that enable a people to make itself master of others, and those that maintain its power once it is acquired.

There is exists in the world at this moment a republic that hardly anyone knows about [canton of Bern], and that—in secrecy and silence—increases its strength every day. Certainly, if it ever attains the greatness for which its wisdom destines it, it will necessarily change its laws. And this will not be the work of a legislator but of corruption itself.

Rome was made for expansion, and its laws were admirable for this purpose. Thus, whatever its government had been—whether the power of kings, aristocracy, or a popular state—it never ceased undertaking enterprises that made demands on its conduct, and succeeded in them. It did not 94 | 95 prove wiser than all the other states on earth for a day, but continually. It sustained meager, moderate and great prosperity with the same superiority, and had neither successes from which it did not profit, nor misfortunes of which it made no use.

It lost its liberty because it completed the work it wrought too soon.

Chapter 10: The Corruption of the Romans8

I believe the sect of Epicurus, which was introduced at Rome toward the end of the republic, contributed much toward tainting the heart and mind of the Romans. The Greeks had been infatuated with this sect earlier and thus were corrupted sooner. Polybius tells us that in this time a Greek’s oaths inspired no confidence, whereas a Roman was, so to speak, enchained by his…97 | 98

Aside from the fact that religion is always the best guarantee one can have of the morals of men, it was a special trait of the Romans that they mingled some religious sentiment with their love of country. This city, founded under the best auspices; this Romulus, their king and their god; this Capitol, eternal like the city, and this city, eternal like its founder—these, in earlier times, had made an impression on the mind of the Romans which it would have been desirable to preserve.

The greatness of the state caused the greatness of personal fortunes. But since opulence consists in morals, not riches, the riches of the Romans, which continued to have limits, produced a luxury and profusion which did not. Those who had at first been corrupted by their riches were later corrupted by their poverty. With possessions beyond the needs of private life it was difficult to be a good citizen; with the desires and regrets of one whose great fortune has been ruined, one was ready for every desperate attempt. And, as Sallust says, a generation of men arose who could neither have a patrimony nor endure others having any.

Yet, whatever the corruption of Rome, not every misfortune was introduced there. For the strength of its institutions had been such that it preserved it heroic valor and all of its application to war in the midst of riches, indolence and sensual pleasures—which, I believe, has happened to no other nation in the world.

Roman citizens regarded commerce9 and the arts as the 98 | 99 occupation of slaves10: they did not practice them. If there were any exceptions, it was only on the part of some freedmen who continued their original work. But, in general, the Romans knew only the art of war, which was the sole path to magistracies and honors.11 Thus, the martial virtues remained after all the others were lost.

Footnotes

- Montesquieu, Anne M. Cohler, et al, eds., The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 22-23. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, Anne M. Cohler, et al, eds., The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 241. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, Anne M. Cohler, et al, eds., The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 250. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, Anne M. Cohler, et al, eds., The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 479. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, Anne M. Cohler, et al, eds., The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 482. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, David Lowenthal, trans., Considerations on the Causes of The Greatness of the Romans and Their Decline (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1999), 91-95. ↩︎

- These were the assemblies into which the Roman people were organized for electoral purposes. ↩︎

- Montesquieu, David Lowenthal, trans., Considerations on the Causes of The Greatness of the Romans and Their Decline (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1999), 97-99. ↩︎

- Romulus permitted free men only two kinds of occupation—agriculture and war. Merchants, artisans, those who paid rent for their house, and tavern-keepers were not numbered among the citizens. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, II (28), IX (25). ↩︎

- Cicero gives the reasons for this in his Offices, I, 42. ↩︎

- It was necessary to have served ten years, between the ages of sixteen and forty-seven. See Polybius, VI (19). ↩︎