(Updated May 28, 2025)

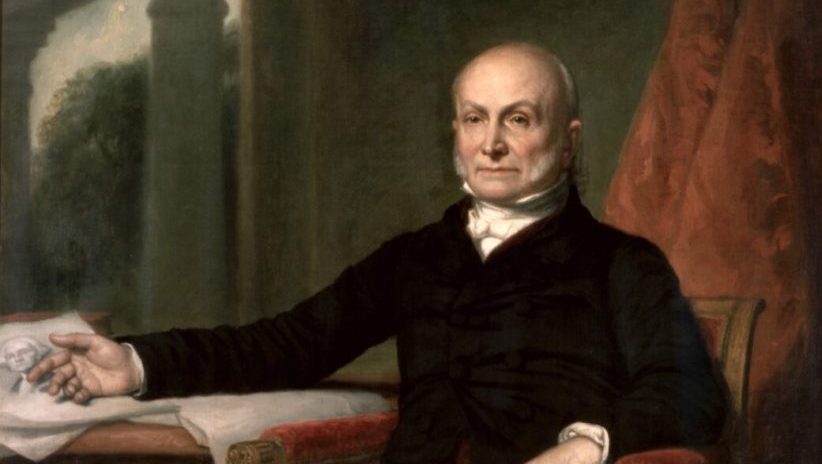

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was the eldest son of American Founders John and Abigail Adams. A lawyer by training, he devoted his entire life to public service. Among other roles, he served as a Representative and Senator in Congress, and the United States’ eighth Secretary of State and sixth President.

Speeches

John Quincy Adams, Inaugural Address (March 4, 1825)

To the guidance of the legislative councils, to the assistance of the executive and subordinate departments, to the friendly cooperation of the respective State governments, to the candid and liberal support of the people so far as it may be deserved by honest industry and zeal, I shall look for whatever success may attend my public service; and knowing that “except the Lord keep the city the watchman waketh but in vain” (Ps. 127:1), with fervent supplications for His favor, to His overruling providence I commit with humble but fearless confidence my own fate and the future destinies of my country.

John Quincy Adams, Oration at Newburyport on the 61st Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1837)1

Why is it, friends and fellow citizens, that you are here assembled [for 4th of July celebrations]? Why is it, that, entering upon the sixty-second year of our national existence, you have honored with an invitation to address you from this place, a fellow citizen of a former age, bearing in the records of his memory, the warm and vivid affections which attached him, at the distance of a fully half century, to your town, and to your forefathers, then the cherished associates of his youthful days? Why is it that, next to the birthday of the Savior of the World, your most joyous and most venerated festival returns on this day? And why is it that, among the swarming myriads of our population, thousands and tens of thousands among us, abstaining, under the dictate of religious principle, from the commemoration of that birth day of Him, who brought life and immortality to light, yet unite with all their brethren of this community, year after year, in celebrating this, the birthday of the nation?

Is it not that, in the chain of human events, the birthday of the nation is indissolubly linked with the birthday of the Savior? That it forms a leading event in the progress of the gospel dispensation? Is it not that the 5 | 6 Declaration of Independence first organized the social compact on the foundation of the Redeemer’s mission upon earth? That it laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity, and gave to the world the first irrevocable pledge of the fulfillment of the prophecies, announced directly from Heaven at the birth of the Savior and predicted by the greatest of the Hebrew prophets six hundred years before?… 6 | 12

This was indeed a great and solemn event. The sublimest of the prophets of antiquity with the voice of inspiration had exclaimed, “Who hath heard such a thing? Who hath seen such things? Shall the earth be made to bring forth in one day? Or shall a nation be born at once?” (Isa. 66:8). In two thousand five hundred years, that had elapsed since the days of that prophecy, no such event had occurred. It had never been seen before. In the annals of the human race, then, for the first time, did one People announce themselves as a member of that great community of the powers of the earth, acknowledging the obligations and claiming the rights of the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God. The earth was made to bring forth in one day! A Nation was born at once!… 12 | 17

[T]he Declaration of Independence announced the One People, assuming their station among the powers of the earth, as a civilized, religious, and Christian people—acknowledging themselves bound by the obligations, and claiming the rights, to which they were entitled by the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God… 17 | 18 They were an independent Nation of Christians, recognizing the general principles of the European law of nations… 18 | 19

The theocratic government of the Hebrews had been founded upon a covenant between God and man; a law, given by the Creator of the world, and solemnly accepted by the people of Israel. It derived all its powers, 19 | 20 therefore, from the consent of the governed, and gave the sanction of Heaven itself to the principle, that the consent of the governed is the only legitimate source of authority to man over man… 20 | 22

The act of abolishing the government under which they had lived—of renouncing and abjuring the allegiance by which they had been bound—of dethroning their sovereign, and of discarding their country herself—purified and elevated by the principles which they proclaimed, and by the motives which they promulgated as their stimulants to action—stands recorded in the annals of the 22 | 23 human race as one among the brightest achievements of human virtue—applauded on earth, ratified and confirmed by the fiat of Heaven… 23 | 53

[T]he Declaration of Independence, with the voice of an angel from heaven, “put to his mouth the sounding alchemy,” and proclaimed universal emancipation upon earth!… 53 | 54 It is not that this is the birthday of the North American Union, the last and noblest offspring of time. It is that the first words uttered by the Genius of our country, in announcing his extensive to the world of mankind, was—Freedom to the slave! Liberty to the captives! Redemption! Redemption forever to the race of man, from the yoke of oppression! It is not the work of a day; it is not the labor of an age; it is not the consummation of a century, that we are assembled to commemorate. It is the emancipation of our race. It is the emancipation of man from the thraldom of man!… 54 | 64

Turn then your faces and raise your hands to God, and pray that, in the merciful dispensations of his providence, he would hasten that happy time [the messianic age]. Turn to yourselves, and, in the Declaration of Independence of your fathers, read the command to you, by the unremitting exercise of your highest energies, to hasten, yourselves, its consummation.

Letters

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (September 1/8, 1811)2

On the Bible

[S]o great is my veneration for the Bible, and so strong my belief, that when duly read and meditated on, it is of all books in the world that which contributes most to make men good, wise, and happy—that the earlier my children begin to read it, the more steadily they pursue the practice 9 | 10 of reading it through their lives, the more lively and confident will be my hopes that they will prove useful citizens to their country, respectable members of society, and a real blessing to their parents. But I hope you have now arrived at an age to understand that reading, even in the Bible, is a thing in itself, neither good nor bad, but that all the good which can be drawn from it is by the use and improvement of what you have read, with the help of your own reflection…

I advise you, my son, in whatever you read, and most of all in reading the Bible, to remember that it is for the purpose of making you wiser and more virtuous. I have myself, for many years, 10 | 11 made it a practice to read through the Bible once every year. I have always endeavored to read it with the same spirit and temper of mind which I now recommend to you: that is, with the intention and desire that it may contribute to my advancement in wisdom and virtue. My desire is indeed very imperfectly successful; for, like you, and like the Apostle Paul, “I find a law in my members warring against the laws of my mind” (Rom. 7:23). But as I know that it is my nature to be imperfect, so I know that it is my duty to aim at perfection; and feeling and deploring my own frailties, I can only pray Almighty God for the aid of his Spirit to strengthen my good desires, and to subdue my propensities to evil; for it is from him that every good and every perfect gift descends. [Jas. 1:17] My custom is to read five chapters every morning, immediately after rising from my bed. It employs 11 | 12 about an hour of my time, and seems to me the most suitable manner of beginning the day…useful thoughts often arise in the mind, and pass away without being remembered or applied to any good purpose—like the seed scattered upon the surface of the ground which the birds devour, or the mind blows away, or which rot without taking root, however good the soil may be upon which they are cast.

We are all, my dear George [his son], unwilling to confess our own faults, even to ourselves: and when our own consciences are too honest to conceal them from us, our self-love is always busy, either in attempting to disguise 12 | 13 them to us under false and delusive colors, or in seeking out excuses and apologies to reconcile them to our minds. Thus, although I am sensible that I have not derived from my assiduous perusal of the Bible…all the benefit that I might and ought, I am as constantly endeavoring to persuade myself that it is not my own fault…

[T]here are many things in the Bible “hard to understand” (2 Pet. 3:16), as St. Peter expressly says of Paul’s epistles: some are hard in the Hebrew, and some in the Greek—the original languages in which the Scriptures were written; some are harder still in the translations…13 | 15

I have thought if in addition to the hour which I daily give to the reading of the Bible, I should also from time to time 15 | 16 (and especially on the Sabbath) apply another hour occasionally to communicate to you the reflections that arise in my mind upon its perusal, it might not only tend to fix and promote my own attention to the excellent instructions of that sacred book, but perhaps also assist your advancement in its knowledge and wisdom…16 | 17

[Reason he is recommending the Bible] It is essential, my son, in order that you may go through life with comfort to yourself, and usefulness to your fellow-creatures, that you should form and adopt certain rules or principles for the government of your own conduct and temper. Unless you have such rules and principles, there will be numberless occasions on which you will have no guide for your government but your passions…17 | 18

[Y]ou know the difference between right and wrong, and you know some of your duties and the obligations you are under to become acquainted with them all. It is in the Bible you must learn them, and from the Bible how to practice them. Those duties are to God, to your fellow-creatures, and to yourself. “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength, and thy neighbor as thyself” (Matt. 22:37-39; Mark 12:30-31; Luke 10:27). On these two commandments, Jesus Christ expressly says, “hang all the law and the prophets.” That is to say, the whole purpose of Divine Revelation is to inculcate them efficaciously upon the minds of men.

You will perceive that I have spoken of 18 | 19 duties to yourself, distinct from those to God and to your fellow-creatures; while Jesus Christ speaks only of two commandments. The reason is, because Christ, and the commandments repeated by him, consider self-love as so implanted in the heart of every man by the law of his nature that it requires no commandment to establish its influence over the heart; and so great do they know its power to be that they demand no other measure for the love of our neighbor than that which they know we shall have for ourselves. But from the love of God, and the love of our neighbor, result duties to ourselves as well as to them, and they are all to be learned in equal perfection by our searching the Scriptures…19 | 20

The Bible contains the revelation of the will of God. It contains the history of the creation of the world and of mankind; and afterward the history of one peculiar nation, certainly the most extraordinary nation that has ever appeared upon the earth. It contains a system of religion and of morality which we may examine upon its own merits, independent of the sanction it receives from being the Word of God; and it contains a numerous collection of books, written at different ages of the world, by different authors which we may survey as curious monuments of antiquity and as literary compositions. In what light soever we regard it, whether with reference to revelation, to literature, to history, or to morality—it is an invaluable and inexhaustible mine of knowledge and virtue.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (September 15, 1811)3

On the Bible

The first point of view in which I have invited you to consider the Bible is in the light of Divine Revelation. And what are we to understand by these terms?…My idea of the Bible as a Divine Revelation is founded upon its practical use to mankind, and not upon metaphysical subtleties.

There are three points of doctrine, the belief of which forms the foundation of all morality. The first is the existence of a God; the second is 22 | 23 the immortality of the human soul; and the third is a future state of rewards and punishments. Suppose it is possible for a man to disbelieve either of these articles of faith, and that man will have no conscience, he will have no other law than that of the tiger or the shark; the laws of man may bind him in chains, or may put him to death, but they never can make him wise, virtuous, or happy.

It is possible to believe them all without believing that the Bible is a Divine revelation. It is so obvious to every reasonable being that he did not make himself, and the world which he inhabits could as little make itself that the moment we begin to exercise the power of reflection, it seems impossible to escape the conviction that there is a Creator.

It is equally evident that the Creator must be a spiritual, and not a material being; there is also a consciousness that the thinking 23 | 24 part of our nature is not material, but spiritual—that it is not subject to the laws of matter, nor perishable with it. Hence arises the belief that we have an immortal soul; and pursuing the train of thought which the visible creation and observation upon ourselves suggest, we must soon discover that the Creator must also be the Governor of the universe; that his wisdom and his goodness must be without bounds—that he is a righteous God, and loves righteousness—and that mankind are bound by the laws of righteous, and are accountable to him for their obedience to them in this life, according to their good or evil deeds. This completion of Divine justice must be reserved for another life.

The existence of a Creator, the immortality of the human soul, and a future state of retribution, are therefore so perfectly congenial to natural reason when once discovered 24 | 25—or rather it is so impossible for natural reason to disbelieve them—that it would seem the light of natural reason could alone suffice for their discovery; but the conclusion would not be correct. Human reason may be sufficient to get an obscure glimpse of these sacred and important truths, but it cannot discover them in all their clearness. For example—in all their numberless, false religions, which have swayed the minds of men in different ages, and regions of the world, the idea of a God has always been included:

“Father of all in every age,

In every clime adored—

By saint, by savage, and by sage—

Jehovah, Jove, or Lord.”

So says Pope’s Universal Prayer.But it is the God of the Hebrews alone, who is announced to us as the Creator of the world. The ideas of God entertained by 25 | 26 all the most illustrious and most ingenious nations of antiquity were weak and absurd…[S]carcely any of them reflected enough even to imagine that there was but one God, and not one of them ever conceived of him as the Creator of the world. Cicero has collected together all their opinions upon the nature of the gods, and pronounced them more like the dreams of madmen then the sober judgment of wise men…

[Contrasting with pagan religion which saw the gods as merely the organizers of primeval chaos, rather than the Creator] But the first words of the Bible are, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” The blessed and sublime idea of God, as the creator of the universe, the source of all human happiness for which all the sages and philosophers of Greece and Rome groped in darkness and never found, is recalled in the first verse of the book of Genesis. I call it the source of all human virtue and happiness; because when we have attained the conception of a Being, who by the mere act of his will, created the 27 | 28 world, it would follow as an irresistible consequence—even if we were not told that the same Being must also be the governor of his own creation—that man, with all other things, was also created by him, and must hold his felicity and virtue on the conditions of obedience to his will.

In the first chapters of the Bible there is a short and rapid historical narrative of the manner in which the world and man were made—of the condition upon which happiness and immortality were bestowed upon our first parents—of their transgression of this condition—of the punishment denounced upon them—and the promise of redemption from it by the “seed of the woman” (Gen. 3:15).

There are, and always have been, where the Holy Scriptures have been known, petty witlings and self-conceited reasoners, who cavil at some of the particular details of this narration. Even serious 28 | 29 inquirers after truth have sometimes been perplexed to believe that there should have been evening and morning before the existence of the sun—that man should be made of clay, and woman from the ribs of man—that they should have been forbidden to eat an apple, and for disobedience to that injunction, be with all their posterity doomed to death, and that eating an apple could give “the knowledge of good and evil”—that a serpent should speak and beguile a woman.

All this is undoubtedly marvelous, and above our comprehension. Much of it is clearly figurative and allegorical; nor is it easy to distinguish what part of it is to be understood in a literal and not in a symbolical sense. But all that it imports us to know or understand is plain; the great and essential principles, upon which our duties and enjoyments depend, are involved in no obscurity. A God, 29 | 30 the Creator and Governor of the universe, is revealed in all his majesty and power: the terms upon which he gave existence and happiness to the common parent of mankind are exposed to us in the clearest light. Disobedience to the will of God was the offence for which he was precipitated from paradise: obedience to the will of God is the merit by which paradise is regained.

Here, then, is the foundation of all morality—the source of all our obligations, as accountable creatures. This idea of the transcendent power of the Supreme Being is essentially connected with that by which the whole duty of man is summed up; obedience to his will. I have observed that natural reason might suffice for an obscure perception, but not for the clear discovery of these truths…30 | 31

The ray of divine light contained in the principles, that justice has no other foundation than piety, could make its way to the soul of the heathen, but there it was extinguished in the low, unsettled, and inconsistent notions which were the only foundations of his piety. How could his piety be pure or sound, when he did not know whether there was one God or a thousand—whether he, or they had or had not any concern in the formation of the world, and whether they had any regard to the affairs or the conduct of mankind?

Once assume the idea of a single God, the Creator of all things, whose will is the law of moral obligation to man, and to whom man is accountable, and piety becomes as rational as it is essential; it becomes the first of human duties; and not a doubt can henceforth remain, that fidelity in the 31 | 32 associations of human piety, and that most excellent virtue, justice, repose upon no other foundation.

At a later age than Cicero, Longinus expressly quotes the third verse of the first chapter of Genesis as an example of the sublime. “And God said let there be light, and there was light” (Gen. 1:3) and wherein consists its sublimity? In the image of the transcendent power presented to the mind, with the most striking simplicity of expression. Yet this verse only exhibits the effects of that transcendent power which the first verse discloses in announcing God as the Creator of the world. The true sublimity is in the idea given us of God. To such a God the heart of man must yield with cheerfulness the tribute of homage which it never could pay to the numerous gods of Egypt, to the dissolute debauchees of the heathen mythology, nor even to the 32 | 33 more elevated, but not less fantastical imaginations of the Grecian philosophers and sages.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (September 29, 1811)4

On the Bible

To a man of liberal education, the study of history is not only useful, and important, but altogether indispensable, and with regard to the history contained in the Bible, the observation which Cicero makes respecting that of his own country is much more emphatically applicable, that “it is not so much praiseworthy to be acquainted with as it is shameful to be ignorant of.” (34)

History, so far as it 34 | 35 relates to the actions and adventures of men, may be divided into five different classes. First, the history of the world, otherwise called universal history; second, that of particular nations; third, that of particular institutions; fourth, that of single families; and fifth, that of individual men…All these classes of history are to be found in the Bible, and it may be worth your while to discriminate them one from another. The universal history is short; and all contained in the first eleven chapters of Genesis, together with the first chapter of the first book of Chronicles, which is little more than a genealogical list of names; but it is of great importance, not only as it includes the history of the creation, of the fall of man, of the antediluvian [pre-flood] world, and the flood by which the whole 35 | 36 human race (excepting Noah and his family) were destroyed, but as it gives a very precise account of the time from the creation until the birth of Abraham.

This is the foundation of ancient history, and in reading profane historians hereafter, I would advise you always to reflect upon their narratives with reference to it with respect to the chronology. A correct idea of this is so necessary to understand all history, ancient and modern, that I may hereafter write you something further concerning it: for the present I shall only recommend to your particular attention the fifth and eleventh chapters of Genesis, and request you to cast up and write me the amount of the age of the world when Abraham was born.

The remainder of the book of Genesis, beginning at the twelfth chapter, is a history of one individual (Abraham) and his family during three generations of his descendants, 36 | 37 after which the book of Exodus commences with the history of the same family, multiplied into a nation; this national and family history is continued through the books of the Old Testament until that of Job, which is of a peculiar character, differing in many particulars from every other part of the Scriptures.

There is no other history extant which can give so interesting and correct view of the rise and progress of human associations, as this account of Abraham and his descendants, through all the vicissitudes to which individuals, families, and nations, are liable. There is no other history where the origin of a whole nation is traced up to a single man, and where a connected train of events and a regular series of persons from generation to generation is preserved.

As the history of a family, it is intimately connected with our religious principles and opinions, for it is 37 | 38 the family from which (in his human character) Jesus Christ descended. It begins by relating the commands of God to Abraham, to abandon his country, his kindred, and his father’s house; and to go to a land which he would show them. This command was accompanied by two promises; from which, and from their fulfillment, arose the differences which I have just noted between the history of the Jews and that of every other nation. The first of these promises was that “God would make Abraham a great nation, and bless him” (Gen. 12:2); the second, and incomparably the most important was, that “in him all the families of the earth should be blessed” (Gen. 12:3). This promise was made about two thousand years before the birth of Christ, and in him had its fulfillment.

When Abraham, in obedience to the command of God, had gone into the land of Canaan, the Lord appeared unto him and 38 | 39 made him a third promise, which was that he should give that land to a nation which should descend from him, as a possession: this was fulfilled between five and six hundred years afterward. In reading all the historical books of both the Old and the New Testament, as well as the books of the prophets, you should always bear in mind the reference which they have to these three promises of God to Abraham. All the history is no more than a narrative of the particular manner, and the detail of events by which those promises were fulfilled.

In the account of the creation, and the fall of man, I have already remarked that the moral doctrine inculcated by the Bible is, that the great consummation of all human virtue consists in obedience to the will of God. When we come hereafter to speak of the Bible in its ethical character, I shall endeavor to show you the 39 | 40 intrinsic excellence of this principle; but I shall now only remark how strongly the principle itself is illustrated, first the account of the fall, and next by the history of Abraham. In the account of the creation we are informed that God, after having made the world, created the first human pair, and “gave them dominion over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (Gen. 1:28). He gave them also “every herb bearing seed, and the fruit of every tree for meat” (Gen. 1:29); and all this we are told “God saw was very good.” Thus the immediate possession of everything was given them, and its perceptual enjoyment secured to their descendants, on condition of abstaining from the “fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil” (Gen. 2:17).

It is altogether immaterial to my present remarks whether the narrative is to be understood in a literal or allegorical sense, as not only the knowledge, but the 40 | 41 possession of created good was granted; the fruit of the tree, could confer upon them no knowledge but that of evil, and the command was nothing more than to abstain from that knowledge—to forbear from rushing upon their own destruction. It is not sufficient to say that this was a command in its own nature light and easy; it was a command to pursue the only law of their nature, to keep the happiness that had been heaped upon them without measure; but observe—it contained the principle of obedience—it was assigned to them as a duty—and the heaviest of penalties was denounced upon its transgression. They were not to discuss the wisdom, or justice of this command; they were not to inquire why it had been enjoined upon them, nor could they have the slightest possible motive for the inquiry: unqualified felicity and immortality were already theirs; wretchedness 41 | 42 and death were alone forbidden them, but placed within their reach as merely trials of their obedience.

They violated the law; they forfeited their joy and immortality; they “brought into the world, death, and all our woe” (Rom. 5:12). Here, then, is an extreme case in which the mere principle of obedience could be tried, and command to abstain from that from which every motive of reason and interest would have deterred had the command never been given—a command given in the easiest of all possible form, requiring not so much as an action of any kind, but merely forbearance: and its transgression was so severely punished, and the only inference we can draw from it is that the most aggravated of all crimes, and that which includes in itself all others, is disobedience to the will of God.

Let us now consider how the principle of obedience [to God] is inculcated in the history 42 | 43 of Abraham, by a case in the opposite extreme. God commanded Abraham to abandon forever his country, his kindred, and his father’s house, to go, he knew not where; promising, as a reward of his obedience, to bless him and his posterity, though he was then childless: he was required to renounce everything that could most contribute to the happiness and comfort of his life, and which was in his actual enjoyment; to become a houseless, friendless wanderer upon the earth, on the mere faith of the promise that a land should be shown him which his descendants should possess—that they should be a great nation—and that through them all mankind should receive in future ages a blessing.

The obedience required of Adam, was merely to retain all the blessings he enjoyed; the obedience of Abraham was to sacrifice all that he possessed for the vague and distant prospect of a 43 | 44 future compensation to his posterity: the self-control and self-denial required of Adam, was in itself the slightest that imagination can conceive—but its failure was punished by the forfeiture of all his enjoyments; the self-dominion to be exercised by Abraham was of the most severe and painful kind—but its accomplishment will ultimately be rewarded by the restoration of all that was forfeited by Adam.

This restoration, however, was to be obtained by no ordinary proof of obedience; the sacrifice of mere personal blessings, however great, could not lay the foundation for the redemption of mankind from death; the voluntary submission of Jesus Christ to his own death, in the most excruciating and ignominious form, was to consummate the great plan of redemption, but the submission of Abraham to sacrifice his beloved, and only son Isaac—the child promised by God 44 | 45 himself, and through whom all the greater promises were to be carried into effect, the feelings of nature, the parent’s bowels, were all required to be sacrificed by Abraham to the blind unquestioning principle of obedience to the will of God. The blood of Isaac was not indeed shed—the butchery of an only son by the hand of his father, was a sacrifice which a merciful God did not require to be completely executed; but as an instance of obedience it was imposed upon Abraham, and nothing less than the voice of an angel from heaven could arrest his uplifted arm, and withhold him from sheathing his knife in the heart of his child. It was upon this testimonial of obedience, that God’s promise of redemption was expressly renewed to Abraham: “In thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because thou hast obeyed my voice.”—Genesis xxii. 18.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (October 6, 1811)5

On the Bible

We were considering the Bible in its historical character, and as the history of a family. From the moment when the universal history [of the Bible] finishes, that of Abraham begins, and thenceforth, it is the history of a family, of which Abraham is the first, and Jesus Christ the last person; and from the first appearance of Abraham, the whole history appears to have been ordered from age to age, expressly to prepare for the appearance of Christ upon earth.

The history begins with the first and mildest trials of Abraham’s obedience, and the promises as a reward of his fidelity, that “in him all the 46 | 47 families of the earth should be blessed” (Gen. 12:3). The second trial, which required the sacrifice of his son, was many years afterward, and the promise was more explicit, and more precisely assigned as the reward of his obedience.

There were between these periods, two intermediate occasions, recorded in the fifteenth and eighteen chapters of Genesis—on the first of which, the word of the Lord came to Abraham in a vision, and promised him he would have a child, from whom a great and mighty nation should proceed, which, after being in servitude four hundred years in a strange land [Gen. 15:13], should become the possessors of the land of Canaan, from that of Egypt, to the river Euphrates. On the second, the Lord appeared to him and his wife, repeated the promise, that they should have a child, that “Abraham should surely become a great nation,” and that 47 | 48 “all the nations of the earth should be blessed in him” (Gen. 18:18), “for I know him, saith the Lord, that he will command his household after him, and that they will keep the way of the Lord, to do justice and judgment, that the Lord may bring upon Abraham that which he hath spoken of him” (Gen. 18:19), from all which it is obvious that the first of the promises was made as subservient and instrumental to the second—that the great and mighty nation was to be raised as the means in the ways of God’s providence, for producing the sacred person of Jesus Christ, through whom the perfect sacrifice of atonement for the original transgression of man should be consummated, and by which “all the families of the earth should be blessed” (Gen. 12:3)… 48 | 49

[L]et me ask your particular attention, to the reason assigned by God for bestowing such extraordinary blessings upon Abraham. It unfolds to us the first and most important part of the superstructure of moral principle, erected upon the foundation of obedience to the will of God. The rigorous trials of Abraham’s obedience mentioned in this, and my last letter, were only tests to ascertain his character in reference to the single, and I may say abstract point of obedience. Here we have a precious gleam of light, disclosing what 49 | 50 the nature of this will of God was, that he should command his children, and his household after him; by which the parental authority to instruct, and direct his descendants in the way of the Lord was given him as an authority, and enjoined upon him as a duty; and the lessons which he was then empowered and required to teach his posterity were, “to do justice and judgment” (Gen. 18:19).

Thus, as obedience to the will of God, is the first, and all-comprehensive virtue taught in the Bible, so the second is justice and judgment toward mankind; and this is exhibited as the result naturally following from the other.

In the same chapter is related the intercession of Abraham with God for the preservation of Sodom from destruction: the city was destroyed for its crimes, but the Lord promised Abraham it should be spared, if only ten righteous should be found in it: the principle 50 | 51 of mercy was therefore sanctioned in immediate connection with that of justice. Abraham has several children; but the great promise of God was to be performed through Isaac alone, and of the two sons of Isaac, Jacob—the youngest—was selected for the foundation of the second family and nation; it was from Jacob that the multiplication of the family began, and his twelve sons, were all included in the genealogy of the tribes which afterward constituted the Jewish people. Ishmael, the children of Keturah, and Esau, the eldest son of Isaac, were all the parents of considerable families, which afterward spread into nations; but they formed no part of the chosen people, and their history, with that of the neighboring nations, is only incidentally noticed in the Bible, so far as they had relations of intercourse or hostility with the people of God. 51 | 52

The history of Abraham and his descendants to the close of the close of the book of Genesis is a biography of individuals: the incidents related of them are all of the class belonging to domestic life. Joseph, indeed, became a highly distinguished public character in the land of Egypt, and it was through him that his father and all his brothers were finally settled there—which was necessary to prepare for the existence of their posterity as a nation, and to fulfill the purpose which God had announced to Abraham, that they should be four hundred years dwellers in a strange land. In the lives of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph, many miraculous events are recorded; but all those which are spoken of as happening in the ordinary course of human affairs have an air of reality about them which no invention could imitate. In some of the transactions related, the conduct of the patriarchs is 52 | 53 highly blamable; circumstances of deep depravity are particularly told of Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah, upon which it is necessary to remark that their actions are never spoken of with approbation, but always with strong marks of censure, and generally with a minute account of the punishment which followed upon their transgression.

The vices and crimes of the patriarchs, are sometimes alleged as objections against the belief that person guilty of them should ever have been especially favored by God; but, vicious as they were, there is every reason to be convinced that they were less so than their contemporaries: their vices appear to us at this day gross, disgusting and atrocious; but the written law was not then given, the boundaries between right and wrong were not defined with the same precision as in the tables given afterward to Moses; the law of nature was the only 53 | 54 rule of morality by which they could be governed, and the sins of intemperance, of every kind recorded in Holy Writ, were at that period less aggravated than they have been in after ages, because they were in great measure sins of ignorance.

From the time when the sons of Jacob settled in Egypt until the completion of the four hundred years, during which God had foretold to Abraham that his family should dwell there, there is a chasm of sacred history. We are expressly told that all the house of Jacob which came into Egypt, were threescore and ten: it is said then that Joseph died, as did all that generation; after which nothing further is related of their posterity than “they were faithful and multiplied abundantly, and waxed exceeding mighty, and the land was filled with them, until there arose a new king who knew not Joseph” (Ex. 1:7).

On his first arrival in 54 | 55 Egypt, Jacob had obtained a grant from Pharaoh of the land of Goshen, a place particularly suited to the pastorage of flocks: Jacob and his family were shepherds, and this circumstances was, in the first instance, the occasion upon which that separate spot was assigned to them, and, secondarily, was the means provided by God for keeping separate two nations thus residing together: every shepherd was an abomination to the Egyptians, and the Israelites were shepherds, although dwelling in the land of Egypt; therefore, the Israelites were sojourners and strangers; and by mutual antipathy toward each other, originating in their respective conditions, they were prevented from intermingling by marriage, and losing their distinctive characters. This was the cause which had been reserved by the Supreme Creator, during the space of three generations and more 55 | 56 than four centuries, as the occasion for eventually bringing them out of the land; for, in proportion as they multiplied, it had the tendency to excite the jealousies and fears of the Egyptian king—as actually happened.

These jealousies and fears suggested to him [Pharaoh] a policy of the most intolerable oppression and the most execrable cruelty toward the Israelites: not contended with reducing them to the most degraded condition of service, and making their lives bitter with hard bondage, he conceived the project of destroying the whole race, by ordering all the male children to be murdered as soon as they were born. In the wisdom of Providence, this very command was the means of preparing this family—when they had multiplied into a nation—for their issue from Egypt, and for their conquest of the land which had been promised to Abraham; and it was at the same time the 56 | 57 immediate occasion of raising up the great warrior, legislator, and prophet, who was to be their deliverer and leader [Moses]. Thenceforth, they are to be considered as a people, and their history as that of a nation.

During a period of more than a thousand years, the Bible gives us a particular account of their destinies: an outline of their constitution, civil, military, and religious, with the code of laws presented to them by the Deity, is contained in the books of Moses, and will afford us copious materials for future consideration. Their subsequent revolutions of government under Joshua, fifteen successive chiefs denominated judges, and a succession of kings, until they were first dismembered into two separate kingdoms, and after a lapse of some centuries both conquered by the Assyrians and Babylonians, and at the end of seventy years partially restored to their country and their temple, constitute 57 | 58 the remaining historical books of the Old Testament, every part of which is full of instruction. But my present purpose is only to point to your attention to their general historical character.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (January 10, 1813)6

On the Bible

I shall not entangle myself in the controversy which has sometimes been discussed with a tempter not very congenial to either the nature of the question itself or the undoubted principles of Christianity, whether the Bible, like all other systems of morality, lays the ultimate basis of all human duties in self-love, or whether it enjoins duties on the principle of perfect, and disinterested benevolence. Whether the obligations are sanctioned by a promise of reward or a menace of punishment, the ultimate motive for its fulfillment may justly be attributed to selfish considerations. But if obedience to the will of God be the universal and only foundation of all moral duty, special injunctions may 60 | 61 be binding upon the consciences of men, although their performance should not be secured either by the impulse of hope or fear.

The law given from Sinai was a civil and municipal as well as a moral and religious code; it contained many statutes adapted to that time only, and to the particular circumstances of the nation to whom it was given; they could of course be binding upon them, and only upon them, until abrogated by the same authority which enacted them, as they afterward were by the Christian dispensation: but many others were of universal application—laws essential to the existence of men in society, and most of which have been enacted by every nation, which ever professed any code of laws. But the Levitical was given by God himself; it extended to a great variety of objects of infinite importance to the welfare of men, but which could not come within 61 | 62 the reach of human legislation; it combined the temporal and spiritual authorities together, and regulated not only the actions but the passions of those to whom it was given.

Human legislators can undertake only to prescribe the actions of men: they acknowledge their inability to govern the sentiments of the heart; the very law styles it a rule of civil conduct, not of internal principles, and there is no crime in the power of an individual to perpetrate which he may not design, project, and fully intend, without incurring guilt in the eye of human law. It is one of the greatest marks of Divine favor bestowed upon the children of Israel, that the legislator gave them rules not only of action but for the government of the heart.

There were occasionally a few short sententious principles of morality issued from the oracles of Greece; among them, and undoubtedly the most 62 | 63 excellent of them, was that of self-knowledge, which one of the purest moralists and finest poets of Rome expressly says came from Heaven.

But if you would remark the distinguishing characteristics between true and false religion, compare the manner in which the ten commandments were proclaimed by the voice of the Almighty God, from Mount Sinai, with thunder, and lightning, and earthquake, by the sound of the trumpet, and in the hearing of six thousand souls, with the studied secrecy, and mystery, and mummery, with which the Delphic and other oracles of the Grecian gods were delivered.

The miraculous interpositions of Divine power recorded in every part of the Bible, are invariably marked with grandeur and sublimity worthy of the Creator of the world, and before which the gods of Homer, not excepting his Jupiter, dwindle into the 63 | 64 most contemptible pygmies; but on no occasion was the manifestation of the Deity so solemn, so awful, so calculated to make indelible impressions upon the imaginations and souls of the mortals to whom he revealed himself, as when he appeared in the character of their Lawgiver.

The law [of Moses] thus dispensed was, however, imperfect; it was destined to be partly suspended and improved into absolute perfection many ages afterward by the appearance of Jesus Christ upon earth. But to judge of its excellence as a system of laws, it must be compared with human codes which existed or were promulgated at nearly the same age of the world in other nations. Remember, that the law was given 1,490 years before Christ was born, at the time the Assyrian and Egyptian monarchies existed: but of their government and laws we know scarcely anything save what is collected 64 | 65 from the Bible. Of the Phrygian, Lydian, and Trojan states, at the same period, little more is known.

The president Gorget, in a very elaborate and ingenious work on the origin of letters, arts, and sciences, among the ancient nations, says, that “the maxims, the civil and political laws of these people, are absolutely unknown; that not even an idea of them can be formed, with the single exception of the Lydians, of whom Herodotus asserts, that their laws were the same as the Greeks.” The same author contrasts the total darkness and oblivion into which all the institutions of these mighty empires have fallen, with the fullness and clearness and admirable composition of the Hebrew code, which has not only descended to us entire, but still continues the national code of the Jews (scattered as they are over the whole face of the earth), and enters so largely into the 65 | 66 legislation of almost every civilized nation upon the globe. He observes that “these laws have been prescribed by God himself: the merely human laws of other contemporary nations cannot bear any comparison with them.”

But my motive in forming the comparison [between pagan and Jewish law], is to present to your reflections as a proof—and to my mind a very strong proof—of the reality of their divine origin: for how is it that the whole system of government, and administration, the municipal, political, ecclesiastical, military, and moral laws and institutions, which bound in society the numberless myriads of human beings who formed for many successive ages the stupendous myriads of human beings who formed for many successive ages the stupendous monarchies of Africa and Asia, should have perished entirely and been obliterated from the memory of mankind, while the laws of a paltry tribe of shepherds, characterized by Tacitus, and the sneering 66 | 67 infidelity of Gibbons, as “the most despised portion of their slaves,” should not only have survived the wreck of those empires, but remain to this day rules of faith and practice to every enlightened nation of the world, and perishable only with it? The reason is obvious: it is their intrinsic excellence which has preserved them from the destruction which befalls all the works of mortal man.

The precepts in the Decalogue alone (says Gorget), disclose more sublime truths, more maxims essentially suited to the happiness of man, than all the writings of profane antiquity put together can furnish. The more you meditate on the laws of Moses, the more striking and brighter does their wisdom appear. It would be a laborious but not an unprofitable investigation, to reduce into a regular classification, like that of the institutes of Justinian or the Commentaries of Blackstone, the 67 | 68 whole code of Moses, which embraces not only all the ordinary subjects of legislation together with the principles of religion and morality, but laws of ecclesiastical directions concerning the minutest actions and dress of individuals…

The first four commandments are religious 68 | 69 laws, the fifth and tenth are properly and peculiarly moral and domestic rules; the other four are of the criminal department of municipal laws: the unity of the godhead, the prohibition of making graven images to worship: that of taking lightly (or in vain as the English translation expresses it) the name of the Deity, and the injunction to observe the Sabbath as a day sanctified and set apart for his worship, were all intended to inculcate the reverence for the one only and true God—that profound and penetrating sentiment of piety which, in a former letter, I urged as the great and only immovable foundation of all human virtue.

Next to the duties toward the Creator, that of honoring the earthly parents is enjoined: it is to them that every individual owes the greatest obligations, and to them that he is consequently bound by the first and strongest of all earthly ties. 69 | 70 The following commands, applying to the relations between man and his fellow mortals, are all negative, as their application was universal, to every human being: it was not required that any positive acts of benevolence toward them should be performed; but only to abstain from wronging them, either: first, in their persons; second, in their property; third, in their conjugal rights; fourth, in their good name; after which, all the essential enjoyments of life being thus guarded from voluntary injury, the tenth and closing commandment goes to the very source of all human actions—the heart—and positively forbids all those desires which first prompt and lead to every transgression upon the property and right of our fellow-creatures.

Vain, indeed, would be the search among the writings of profane antiquity (not merely of that remote antiquity, but even in the most refined and 70 | 71 philosophical ages of Greece and Rome), to find so broad, so complete and so solid a basis for morality as this Decalogue lays down. Yet I have said it was imperfect—its sanctions, its rewards, its punishments, had reference only to present life, and it had no injunctions of positive beneficence toward our neighbors. Of these the laws was not entirely destitute in its other parts; but, both in this respect and in the other, it was to be perfected by him who brought life and immortality to light in the gospel.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (March 21, 1813)7

On the Bible

I promised you, in my last letters, to state the particulars in which I deemed the Christian dispensation to be an improvement, or perfection of the law delivered at Sinai, considered as including a system of morality; but before I come to this point, it is proper to remark upon the character of the books of the Old Testament, subsequent to those of Moses. Some are historical, some prophetical, and some poetical; and two may be considered as peculiarly of the moral class—one being an affecting dissertation upon the vanity of human life [Ecclesiastes], and another a collection of moral sentences under the 72 | 73 name of Proverbs.

I have already observed that the great immovable and eternal foundation of the superiority of scripture morals, to all other morality, was the idea of God disclosed in them and only in them: the unity of God, his omnipotence, his righteousness, his mercy, and the infinity of his attributes, are marked in every line of the Old Testament, in character which nothing less than blindness, can fail to discern, and nothing less than fraud can misrepresent. This conception of God serving as a basis for the piety of his worshipers, was of course incomparably more rational and more profound, than it was possible that sentiment could be which adored devils for deities, or even that of philosophers, like Socrates, Plato, and Cicero, who with purer and more exalted ideas of the Divine nature, than the rabble of the poets, still considered the existence 73 | 74 of God at all, as a question upon which they could form no decided opinion. You have seen that even Cicero believed the only solid foundation of all human virtue to be piety; and it was impossible that a piety so far transcending that of all other nations should not contain in its consequences a system of moral virtue equally transcendent.

The first of the ten commandments was, that the Jewish people should never admit the idea of any other God—the object of the second, third, and fourth, was merely to impress with greater force the obligation of the first, and to obviate the tendencies and temptations, which might arise to its beings neglected, or disregarded. Throughout the whole law, the same injunctions are continually renewed; all the rites and ceremonies were adapted to root deeper into the hearts and souls of the chosen people, 74 | 75 that the Lord Jehovah was to be forever the sole and exclusive object of love. Reverence and adoration, unbounded as his own nature was the principle; every letter of the law, and the whole Bible is but a commentary upon it, and corollary from it.

The law was given not merely in the form of a commandment from God, but in that of a covenant or compact between the Supreme Creator and the Jewish people; it was sanctioned by the blessing and the curse pronounced upon Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal, and in the presence of the whole Jewish people and strangers, and by the solemn acceptance of the whole people responding amen to every one of the curses denounced for violation on their part of the covenant. From that day until the birth of Christ (a period of about fifteen hundred years) the historical books of the Old Testament, are 75 | 76 no more than a simple record of the fulfillment of the covenant, in all its blessings and curses, exactly adapted to the fulfillment or transgression of its duties by the people.

The nation [Israel] was first governed by Joshua, under the express appointment of God; then by a succession of judges, and afterward by a double line of kings, until conquered and carried into captivity by the kings of Assyria and Babylon: seventy years afterward restored to their country, their temple, and their laws; and again conquered by the Romans, and ruled by their tributary kings and proconsuls. Yet, through all their vicissitudes of fortune, they never complied with the duties to which they had bound themselves by the covenant, without being loaded with the blessings promised on Mount Gerizim, and never departed from them without being afflicted with some of the curses 76 | 77 denounced upon Mount Ebal.

The prophetical books are themselves historical—for prophecy, in the strictest sense, is no more than history related before the event; but the Jewish prophets (of whom there was a succession almost constant, from the time of Joshua to that of Christ) were messengers, specially commissioned of God, to warn the people of their duty, to foretell the punishments which awaited their transgressions, and finally to keep alive by uninterrupted prediction the expectation of the Messiah, “the seed of Abraham, in whom all the families of the earth should be blessed.” With this conception of the Divine nature, so infinitely surpassing that of any other nation—with this system of moral virtue, so indissolubly blending as by the eternal constitution of things must be blended piety—with this uninterrupted series of signs and wonders, prophets and 77 | 78 seers, miraculous interpositions of the omnipotent Creator, to preserve and vindicate the truth—it is lamentable; but to those who know the nature of man, it is not surprising to find the Jewish history little else than a narrative of idolatries and corruption of the Israelites and their monarchs.

That the very people who had heard the voice of God from Mount Sinai, within forty days compel Aaron to make a golden calf, and worship that as the “God who brought them out of the land of Egypt”—that the very Solomon, the wisest of mankind, to whom God had twice revealed himself in visions—the sublime dictator of the temple, the witness, in the presence of the whole people, of the fire from heaven which consumed the offerings from the altar, and of the glory of the Lord that filled the house—that he, in his old age, beguiled by fair idolatresses, should have 78 | 79 fallen from the worship of the ever-blessed Jehovah, to that of Ashtaroth and Milcom, etc., the abomination of all the petty tribes of Judea—that of Baal, and Dagon, etc., the sun, moon, and planets, and all the hosts of heaven—that the mountains and plains, every high place and every grove, should have swarmed with idols, to corrupt the hearts and debase the minds of a people so highly favored of Heaven, the elect of the Almighty—may be among the mysteries of Divine Providence, which it is not given to mortality to explain, but is inadmissible only to those who presume to demand why it has pleased the Supreme Arbiter of events, to create such a being as man.

Observe, however, that amid the atrocious crimes which that nation so often polluted themselves with—through all their servitudes, dismemberments, captivities, and transmigrations—the Divine 79 | 80 light, which had been imparted exclusively to them, was never extinguished; the law delivered from Sinai, was preserved in all purity; the histories which attested its violations and its accomplishments were recorded and never lost. The writings of the prophets, of David, and Solomon, were all inspired with the same idea of the Godhead, the same intertwinement of religion and morality, and the same anticipation of the divine “Immanuel, the God with us”; these survived all the changes of government and of constitutions which befell the people: “the pillar of cloud by day, and the pillar of fire by night”—the law and the prophets, eternal in their nature—went before them unsullied, and unimpaired through all the ruins of rebellion and revolution, of conquest and dispersion, of war, pestilence, and famine.

The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Egyptian 80 | 81 empires, Tyre and Sidon, Carthage, and all the other nations of antiquity, rose and fell in their religious institutions at the same time as in their laws and government…All the gods of the heathens have perished with their makers; for where on the face of the globe, could now be found the being who believes in any one of them? So much more deep and strong was the hold which the God of Abraham and Isaac, and Jacob, took upon the imaginations and 81 | 82 reason of mankind, that I might almost invert the question, and say, “Where is the human being found believing in any God at all, and not believing in him?”

The moral character of the Old Testament, then, is that piety to God is the foundation of all virtue, and that virtue is inseparable from it: but that piety without the practice of virtue itself a crime and the aggravation of all iniquity. All the virtues which are here recognized by the heathen, are inculcated not only with more authority but with more energy of argument and more eloquent persuasion in the Bible than in all the writings of the ancient moralists. In one of the apocryphal books (Wisdom of Solomon), the cardinal virtues are expressly named: “If any man love righteousness, her labors are virtue, for she teacheth temperance, and prudence, and justice, and fortitude; which are such things as 82 | 83 men can have nothing more profitable in this life” (Wis. 8:7). The book of Job, whether considered as history or as an allegorical parable, was written to teach the lessons of patience under affliction, of resignation under Divine chastisement, of undoubted confidence in the justice and goodness of God under every temptation or provocation to depart from it. The morality of the apocryphal books is generally the same as that of the inspired writers, except that in some of them there is more stress laid upon the minor objects of the law, and merely formal ordinances of police, and less continual recurrence to “the weightier matters” (Matt. 23:23). The book of Ecclesiasticus [Sirach], however, contains more wisdom than all the sayings of the seven Grecian sages. It was upon this foundation that the more perfect system of Christian morality was to be raised.

The book of Job, whether considered as history or as an allegorical parable, was written to teach the lessons of patience under afflictions, of resignation under Divine chastisement, of undoubted confidence in the justice and goodness of God under every temptation or provocation to depart from it. But I must defer the consideration to my 83 | 84 next letter. In the meantime, as I have urged that the scriptural idea of God is the foundation of all perfect virtue, and that it is totally different from the ideas of God conceived by any ancient nation, I should recommend it to you in pursuing the Scriptures hereafter to meditate often upon the expressions by which they mark the character of the Deity, and to reflect upon the duties to him and to your fellow mortals which follow by inevitable deductions from them.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (April 4, 1813)8

On the Bible

The imperfections of the Mosaic institution which it was the object of Christ’s mission upon earth to remove, appear to me to have been these: first, The want of a sufficient sanction. The rewards and penalties of the Levitical law had all a reference to the present life. There are many passages in the Old Testament which imply a state of existence after death, and some which directly assert a future state of retribution; but none of these were contained in the delivery of the law. At the time of Christ’s advent, it was so far from being a settled article of the Jewish faith, that it was a subject 85 | 86 of bitter controversy between the two principal sects—of Pharisees who believed in, and Sadducees who denied it. It was the special purpose of Christ’s appearance upon earth, to bring immortality to light. He substituted the rewards and punishments of a future state of existence in the room of all others. The Jewish sanctions were exclusively temporal: those of Christ exclusively spiritual.

Second, the want of universality. The Jewish dispensation was exclusively confined to a small and obscure nation. The purposes of the Supreme Creator in restricting the knowledge of himself to one petty heard of Egyptian slaves, are as inaccessible to our intelligence as those of his having concealed from them, and from the rest of mankind, the certain knowledge of their own immortality; yet the fact is unquestionable. The mission of Christ was intended to communicate to 86 | 87 the whole human race all the permanent advantages of the Mosaic law, super-adding to them—upon the condition of repentance—the kingdom of heaven, the blessing of eternal life.

Third, the complexity of the objections of legislation. I have observed in a former letter, that the law from Sinai comprised, not only all the ordinary subjects of regulation for human societies, but those which human legislators cannot reach. It was a civil law, a municipal law, an ecclesiastical law, a law of police, and a law of morality and religion: it prohibited murder, adultery, theft, and perjury; it prescribed rules for the thoughts as well as for the actions of men. The complexity, however practicable and even suitable for one small national society, could not have attained to all the families of the earth.

The parts of the Jewish law adapted to promote 87 | 88 the happiness of mankind, under every variety of situation and government in which they can be placed, were all recognized and adopted by Christ; and he expressly separated them from the rest. He disclaimed all interference with the ordinary objects of human legislation; he declared that his “kingdom was not of this world”; he acknowledged the authority of the Jewish magistrates; he paid for his own person the tribute to the Romans; he refused in more than one instance to assume the office of judge in matters of legal controversy; he strictly limited the object of his own precepts and authority to religion and morals; he denounced no temporal punishment; he promised no temporal rewards; he took up man as a governable being, where the human magistrate is compelled to leave him, and supplied both precept of virtue and motive for practicing it, such as no 88 | 89 other moralist or legislator ever attempted to introduce.

Fourth, the burdensome duties of positive rites, minute formalities, and expensive sacrifices. All these had a tendency, not only to establish and maintain the separation of the Jews from all other nations, but in process of time had been mistaken by the scribes, and Pharisees, and lawyers, and probably by the body of the people, for the substance of religion.

All the rites were abolished by Christ, or (as Paul expresses it) “were nailed to his cross” (Col. 2:14). You will recollect that I am now speaking of Christianity, not as the scheme of redemption to mankind from the consequences of original sin, but as a system of morality for regulating the conduct of men while on earth; and the most striking and extraordinary feature of its character in this respect, it its tendency and exhortation to absolute perfection. The 89 | 90 language of Christ to his disciples is explicit: “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your father in heaven is perfect” (Matt. 5:48)—and this he enjoins at the conclusion of that precept, so expressly laid down, and so unanswerably argued, to “love their enemies, to bless those who cursed them, and pray for those who despitefully used and persecuted them” (Matt. 5:44).

He seems to consider the temper of benevolence in return for injury, as constituting of itself a perfection similar to that of the Divine nature. It is undoubtedly the greatest conquest which the spirit of man can achieve over its infirmities; and to him who can attain that elevation of virtue which it requires, all other victories over the evil passions must be comparatively easy.

Nor was the absolute perfection merely preached by Christ as doctrine: it was practiced by himself throughout his life; practiced to the last instant of 90 | 91 his agony on the cross; practiced under circumstances of trial, such as no other human being was ever exposed to. He proved by his own example the possibility of that virtue which he taught; and although possessed of miraculous powers sufficient to control all the laws of nature, he expressly and repeatedly declined the use of them to save himself from any part of the sufferings which he was able to endure.

The sum of Christian morality, then, consists in piety to God, and benevolence to man: piety, manifested, not by formal, solemn rites and sacrifices of burnt-offerings, but by repentance, by obedience, by submission, by humility, by the worship of the heart, and by benevolence; not founded upon selfish motives, but superior even to a sense of wrong, or the resentment of injuries.

Worldly prudence is scarcely noticed among all the 91 | 92 instructions of Christ: the pursuit of honors and riches, the objects of ambition and avarice, are strongly discountenanced in many places: and an undue solicitude about the ordinary cares of life is occasionally reproved. Of worldly prudence, there are rules enough in the Proverbs of Solomon, and in the complications of the sons of Sirach; Christ passes no censure upon them, but he left what I call the selfish virtues where he found them.

It was not to proclaim common-place morality that he came down from Heaven; his commands were new; that his disciples should “love one another,” that they should love even strangers, that should “love their enemies.” He prescribed barriers against all the maleficent passions; he gave as a law, the utmost point of perfection of which human powers are susceptible, and at the same time allowed degrees of indulgence and relaxation 92 | 93 to human frailty, proportioned to the power of any individual.

An eminent writer in support of Christianity (Dr. Paley) expresses the opinion, that the direct objection of the Christian revelation was to supply motives, and not rules—sanctions, and not precepts; and he strongly intimates that, independent of the purpose of Christ’s atonement and propitiation for the sins of the world, the only object of his mission upon earth was to reveal a future state, “to bring life and immortality to light.” He does not appear to think that Christ promulgated any new principles of morality; and he positively asserts that “morality, neither in the gospel nor in any other book, can be a subject of discovery, because qualities of actions depend entirely on their effects, which effects, must all along have been the subjects of human experience.” To this I reply in the express words of 93 | 94 Jesus: “A new commandment I give you, that ye love one another” (John 13:34); and I add, that this command explained, illustrated, and dilated, as it was by the whole tenor of his discourses, and especially by the parable of the good Samaritan, appears to me to be not only entirely new, but, in the most rigorous sense of the word, a discovery in morals; and a discovery, the importance of which to the happiness of the human race, as far exceeds any discovery in the physical laws of nature, as the soul is superior to the body.

If it be objected that the principles of benevolence toward enemies, and the forgiveness of injuries, may be found not only in the Old Testament, but even in some of the heathen writers, particularly the discourses of Socrates. I answer, that the same may be said of the immortality of the soul, and of the rewards and punishments of a future state. The doctrine 94 | 95 was not more a discovery than the precept; but their connection with each other, the authority with which they were taught, and the miracles by which they were enforced, belong exclusively to the mission of Christ.

Attend particularly to the miracle recorded in the second chapter of Luke, as having taken place as the birth of Jesus; when the angel of the Lord said to the shepherds: “Fear nor, for behold I bring you glad tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people; for unto you is born this day in the city of David, a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” (Luke 2:10-11). In these words the character of Jesus, as a Redeemer, was announced; but the historian adds: “And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and singing, glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men” (Luke 2:13-14). These words, as I understand them, announced 95 | 96 the moral precept of benevolence as explicitly for the object of Christ’s appearance, as the preceding words had declared the purpose of redemption.

It is related in the life of the Roman dramatic poet, Terence, that when one of the personages of his comedy, the “Self-Tormentor,” the first time uttered on the stage the line “Homo sum, humani nil alienum puto” (“I am a man, nothing human is uninteresting to me”), a universal shout of applause burst forth from the whole audience, and that in so great a multitude of Romans, and deputies from the nations, their subjects and allies, there was not one individual but felt in his heart this noble sentiment. Yet how feeble and defective it is, in comparison with the Christian command of charity as unfolded in the discoveries of Christ and enlarged upon in the writings of his apostles.

The heart of man will always 96 | 97 respond with rapture to this sentiment when there is no selfish or unsocial passion to oppose it: but the command to lay it down as the great and fundamental rule of conduct for human life, and to subdue and sacrifice all the tyrannical and selfish passions to preserve it, this is the peculiar and unfading glory of Christianity; this is the conquest over ourselves, which, without the aid of a merciful God, none of us can achieve, and which it was worthy of his special interposition to enable us to accomplish.

John Quincy Adams, To George Washington Adams (June 23, 1813)9

On the Bible

The whole system of Christianity appears to have been set forth by its Divine Author in his sermon on the mount, recorded in the fifth, sixth, and seventh chapters of Matthew. I intend hereafter to make them the subject of remarks, much more at large, for the present I confine myself merely to general views. What I would impress upon your mind, is infinitely important to the happiness and virtue of your life, as the general spirit of Christianity, and the duties which results from it.

In my last letter, I showed you, from the very words of our Savior, that he commanded his disciples 98 | 99 to aim at absolute perfection, and that this perfection consisted in self-subjugation and brotherly love, in the complete conquest of our own passions, and in the practice of benevolence to our fellow-creatures. Among the Grecian systems of moral philosophy, that of the Stoics resembles the Christian doctrine in the particular of requiring the total subjugation of the passions; and this part of the Stoic principles was adopted by the academies… 99 | 100

The weakness and frailty of our nature, it is not possible to deny—it is too strongly tested by all human experience, as well as by the whole tenor of the Scriptures; but the degree of weakness must be measured by the efforts to overcome it, and not by indulgence to it. Once admit weakness as an argument to forbear exertion, and it results in absolute impotence. It is also very inconclusive reasoning to infer, that because perfection is not absolutely to be obtained, it is therefore not to be sought. Human excellence consists in approximation to perfection: and the only means of approaching to any term, is by endeavoring to obtain the term itself.

With these convictions 100 | 101 upon the mind—with a sincere and honest effort to practice upon them, and with the aid of a divine blessing, which is promised to it, the approaches to perfection may at least be so great, as to nearly answer all the ends which absolute perfection itself could attain. All exertion, therefore, is virtue; and if the tree be judged by its fruit, it is certain that all the most virtuous characters of heathen antiquity, were the disciples of the Stoic doctrine.

But let it even be admitted that a perfect command of the passions is unattainable to human infirmity, it will still be true, that the degree of moral excellence possessed by any individual, is in exact proportion to the degree of control he exercises over himself. According to the Stoics, all vice was resolvable into folly: according to the Christian principle it is all the effect of weakness.

In order to preserve the dominion of our 101 | 102 own passions, it behooves us to be constantly and strictly on our guard against the influence and infection of the passions of others. This caution above all is necessary to youth; and I deem it indispensable to enjoin it upon you—because, as kindness and benevolence comprise the whole system of Christian duties, there may be, and often is, great danger of falling into errors and vice, merely for the want of energy to resist the example or enticement of others. On this point the true character of Christian morality appears to me to have been misunderstood by some of its ablest and warmest defenders… 102 | 104

The founder of Christianity did indeed pronounce distinct and positive blessings upon the “poor in spirit,” which is by no means synonymous with the “poor-spirited”; and upon the meek; but in what part of the gospel did Dr. Paley find him countenancing by “commendation, by precept or example, the tame and abject”? The character which Christ assumed upon earth, was that of a Lord and Master; it was in that character his disciples received and acknowledged 104 | 105 him. The obedience he required was unbounded, infinitely beyond that which was ever claimed by the most absolute earthly sovereign of his subjects: never for one moment did he recede from this authoritative station; he preserved it in washing the feet of his disciples; he preserved it in answer to the officer who struck him for this very deportment to the high-priest; he preserved it in the agony of his ejaculation on the cross, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” He expressly declared himself, “The Prince of this world, and the Son of God.” He spoke as one having authority, not only to his disciples, but to his mother, to his judges, to Pilate, the Roman governor, to John the Baptist his precursor; and there is not in the four gospels, one act, not one word recorded of him (excepting his communion with God), that was not a direct or implied 105 | 106 assertion of authority. He said to his disciples, “Learn of me, for I am meek and lowly of heart” (Matt. 11:29), etc.; but where did he ever say to them, “Learn of me, for I am tame and abject”?

There is certainly nothing more strongly marked in the precepts and examples of Christ, than the principle of stubborn and inflexible resistance against the impulses of others to evil. He taught his disciples to renounce everything that is counted enjoyment upon earth; “to take up their cross,” and to suffer ill-treatment, persecution, and death, for his sake. What else is the book of the “Acts of the Apostles,” than a record of the faithfulness with which these chosen ministers of the gospel carried these injunctions into execution? In the conduct and speeches of Peter, John, and Paul, is there anything that could justly be called “tame or abject”? Is there anything 106 | 107 indicating a resemblance to the second class of character into which Dr. Paley divides all mankind?

If there is a character upon historical record distinguished by a bold, inflexible, tenacious, and intrepid spirit, it is that of Paul. It was to such characters only, that the commission to “teach all nations” (Matt. 28:19-20), could be committed with certainty of success. Observe the impression of Christ, in his charge to Peter (a rock): “And upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18). Dr. Paley’s Christian is one of those drivelers, who, to use a vulgar phrase, can never say no, to anybody.

The true Christian is the “Justum et tenacem propositi virum” of Horace, (“the man who is just and steady to his purpose”). The combination of these qualities so essential to heroic character, with those of meekness, lowliness of heart, and brotherly 107 | 108 love, is what constitutes that moral perfection of which Christ gave an example in his own life, and to which he commands his disciples to aspire.