(Updated May 28, 2025)

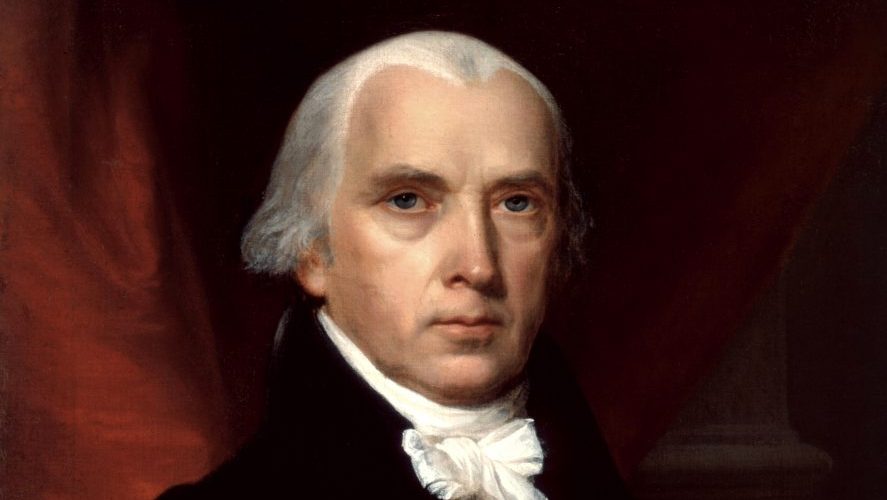

James Madison (1751-1836) was an American Founder who served as the United States’ fifth Secretary of State (1801-1809) and fourth President. He was one of the co-authors of the Federalist Papers, a classic American political text that argued in favor of ratifying the Constitution.

Next to each quote are the Topic Quote Archives in which they are included.

This Quote Archive is being continuously updated as research continues. Quotes marked with “***” have not yet been organized into their respective Topic Quote Archives.

Public Writings

James Madison, A Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (June 20, 1785)

Madison’s Case for Religious Liberty

Because we hold it for a fundamental and undeniable truth, “that Religion or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence” [Article XVI of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, promulgated in 1776]. The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right. It is unalienable, because the opinions of men, depending only on the evidence contemplated by their own minds cannot follow the dictates of other men: It is unalienable also, because what is here a right towards men, is a duty towards the Creator.

It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society. Before any man can be considered as a member of Civil Society, he must be considered as a subject of the Governor of the Universe: And if a member of Civil Society, who enters into any subordinate Association, must always do it with a reservation of his duty to the General Authority; much more must every man who becomes a member of any particular Civil Society, do it with a saving of his allegiance to the Universal Sovereign.

We maintain therefore that in matters of Religion, no man’s right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and that Religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance. True it is, that no other rule exists, by which any question which may divide a Society, can be ultimately determined, but the will of the majority; but it is also true that the majority may trespass on the rights of the minority.

Because if Religion be exempt from the authority of the Society at large, still less can it be subject to that of the Legislative Body. The latter are but the creatures and vicegerents of the former. Their jurisdiction is both derivative and limited: it is limited with regard to the co-ordinate departments, more necessarily is it limited with regard to the constituents…

Because it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties. We hold this prudent jealousy to be the first duty of Citizens, and one of the noblest characteristics of the late Revolution. The freemen of America did not wait till usurped power had strengthened itself by exercise, and entangled the question in precedents. They saw all the consequences in the principle, and they avoided the consequences by denying the principle. We revere this lesson too much soon to forget it. Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects? that the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment, may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?

Because the Bill violates that equality which ought to be the basis of every law, and which is more indispensable, in proportion as the validity or expediency of any law is more liable to be impeached. If “all men are by nature equally free and independent,” all men are to be considered as entering into Society on equal conditions; as relinquishing no more, and therefore retaining no less, one than another, of their natural rights. Above all are they to be considered as retaining an “equal title to the free exercise of Religion according to the dictates of Conscience.”

Whilst we assert for ourselves a freedom to embrace, to profess and to observe the Religion which we believe to be of divine origin, we cannot deny an equal freedom to those whose minds have not yet yielded to the evidence which has convinced us. If this freedom be abused, it is an offense against God, not against man: To God, therefore, not to man, must an account of it be rendered…

Because the Bill implies either that the Civil Magistrate is a competent Judge of Religious Truth; or that he may employ Religion as an engine of Civil policy. The first is an arrogant pretension falsified by the contradictory opinions of Rulers in all ages, and throughout the world: the second an unhallowed perversion of the means of salvation.

Because the establishment proposed by the Bill is not requisite for the support of the Christian Religion. To say that it is, is a contradiction to the Christian Religion itself, for every page of it disavows a dependence on the powers of this world: it is a contradiction to fact; for it is known that this Religion both existed and flourished, not only without the support of human laws, but in spite of every opposition from them, and not only during the period of miraculous aid, but long after it had been left to its own evidence and the ordinary care of Providence. Nay, it is a contradiction in terms; for a Religion not invented by human policy, must have pre-existed and been supported, before it was established by human policy. It is moreover to weaken in those who profess this Religion a pious confidence in its innate excellence and the patronage of its Author; and to foster in those who still reject it, a suspicion that its friends are too conscious of its fallacies to trust it to its own merits.

Because experience witnesseth that ecclesiastical establishments, instead of maintaining the purity and efficacy of Religion, have had a contrary operation. During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution…

Because the establishment in question is not necessary for the support of Civil Government. If it be urged as necessary for the support of Civil Government only as it is a means of supporting Religion, and it be not necessary for the latter purpose, it cannot be necessary for the former. If Religion be not within the cognizance of Civil Government how can its legal establishment be necessary to Civil Government? What influence in fact have ecclesiastical establishments had on Civil Society? In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of the Civil authority; in many instances they have been seen upholding the thrones of political tyranny: in no instance have they been seen the guardians of the liberties of the people. Rulers who wished to subvert the public liberty, may have found an established Clergy convenient auxiliaries.

A just Government instituted to secure and perpetuate it needs them not. Such a Government will be best supported by protecting every Citizen in the enjoyment of his Religion with the same equal hand which protects his person and his property; by neither invading the equal rights of any Sect, nor suffering any Sect to invade those of another.

Because the proposed establishment is a departure from that generous policy, which, offering an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion, promised a luster to our country, and an accession to the number of its citizens. What a melancholy mark is the Bill of sudden degeneracy? Instead of holding forth an Asylum to the persecuted, it is itself a signal of persecution. It degrades from the equal rank of Citizens all those whose opinions in Religion do not bend to those of the Legislative authority. Distant as it may be in its present form from the Inquisition, it differs from it only in degree. The one is the first step, the other the last in the career of intolerance. The magnanimous sufferer under this cruel scourge in foreign Regions, must view the Bill as a Beacon on our Coast, warning him to seek some other haven, where liberty and philanthropy in their due extent, may offer a more certain repose from his Troubles…

Because it will destroy that moderation and harmony which the forbearance of our laws to intermeddle with Religion has produced among its several sects. Torrents of blood have been spilt in the old world, by vain attempts of the secular arm, to extinguish Religious discord, by proscribing all difference in Religious opinion….If with the salutary effects of this system under our own eyes, we begin to contract the bounds of Religious freedom, we know no name that will too severely reproach our folly. At least let warning be taken at the first fruits of the threatened innovation. The very appearance of the Bill has transformed “that Christian forbearance, love and charity,” which of late mutually prevailed, into animosities and jealousies, which may not soon be appeased. What mischiefs may not be dreaded, should this enemy to the public quiet be armed with the force of a law?

Because the policy of the Bill is adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity. The first wish of those who enjoy this precious gift ought to be that it may be imparted to the whole race of mankind. Compare the number of those who have as yet received it with the number still remaining under the dominion of false Religions; and how small is the former!

Does the policy of the Bill tend to lessen the disproportion? No; it at once discourages those who are strangers to the light of revelation from coming into the Region of it; and countenances by example the nations who continue in darkness, in shutting out those who might convey it to them. Instead of Levelling as far as possible, every obstacle to the victorious progress of Truth, the Bill with an ignoble and unchristian timidity would circumscribe it with a wall of defense against the encroachments of error…

Because finally, “the equal right of every citizen to the free exercise of his Religion according to the dictates of conscience” is held by the same tenure with all our other rights. If we recur to its origin, it is equally the gift of nature; if we weigh its importance, it cannot be less dear to us; if we consult the “Declaration of those rights which pertain to the good people of Virginia, as the basis and foundation of Government,” it is enumerated with equal solemnity, or rather studied emphasis. Either then, we must say, that the Will of the Legislature is the only measure of their authority; and that in the plenitude of this authority, they may sweep away all our fundamental rights; or, that they are bound to leave this particular right untouched and sacred…

We the Subscribers say, that the General Assembly of this Commonwealth have no such authority: And that no effort may be omitted on our part against so dangerous an usurpation, we oppose to it, this remonstrance; earnestly praying, as we are in duty bound, that the Supreme Lawgiver of the Universe, by illuminating those to whom it is addressed, may on the one hand, turn their Councils from every act which would affront his holy prerogative, or violate the trust committed to them: and on the other, guide them into every measure which may be worthy of his [blessing, may re]dound to their own praise, and may establish more firmly the liberties, the prosperity and the happiness of the Commonwealth.

James Madison, Federalist No. 37 (January 11, 1788)

The real wonder is that so many difficulties should have been surmounted [in forming the Constitution], and surmounted with a unanimity almost as unprecedented as it must have been unexpected. It is impossible for any man of candor to reflect on this circumstance without partaking of the astonishment. It is impossible for the man of pious reflection not to perceive in it a finger of that Almighty hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution.

James Madison, Federalist No. 51 (February 8, 1788)

But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

James Madison, Federalist No. 52 (February 8, 1788)

Under these reasonable limitations, the door of this part of the federal government is open to merit of every description, whether native or adoptive, whether young or old, and without regard to poverty or wealth, or to any particular profession of religious faith.

Official Documents and Speeches (President, 1809-1817)

James Madison, Presidential Proclamation (July 9, 1812)

Prayer and Fasting

Whereas the Congress of the United States, by a joint Resolution of the two Houses, have signified a request, that a day may be recommended, to be observed by the People of the United States, with religious solemnity, as a day of public Humiliation and Prayer: and whereas such a recommendation will enable the several religious denominations and societies so disposed, to offer, at one and the same time, their common vows and adorations to Almighty God, on the solemn occasion produced by the war, in which he has been pleased to permit the injustice of a foreign power to involve these United States; I do therefore recommend the third Thursday in August next, as a convenient day, to be so set apart, for the devout purposes of rendering to the Sovereign of the Universe, and the Benefactor of mankind, the public homage due to his holy attributes; of acknowledging the transgressions which might justly provoke the manifestations of His divine displeasure; of seeking His merciful forgiveness, and His assistance in the great duties of repentance and amendment; and, especially, of offering fervent supplications, that in the present season of calamity and war, he would take the American People under His peculiar care and protection; that He would guide their public councils, animate their patriotism, and bestow His blessing on their arms; that He would inspire all nations with a love of justice and of concord, and with a reverence for the unerring precept of our holy religion, to do to others as they would require that others should do to them; and, finally, that turning the hearts of our enemies from the violence and injustice which sway their councils against us, He would hasten a restoration of the blessings of Peace. Given at Washington the ninth day of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twelve.

James Madison, Proclamation on Day of Public Humiliation and Prayer (July 23, 1813)

Prayer and Fasting

Whereas in times of public calamity such as that of the war brought on the United States by the injustice of a foreign government it is especially becoming that the hearts of all should be touched with the same and the eyes of all be turned to that Almighty Power in whose hand are the welfare and the destiny of nations:

I do therefore issue this my proclamation, recommending to all who shall be piously disposed to unite their hearts and voices in addressing at one and the same time their vows and adorations to the Great Parent and Sovereign of the Universe that they assemble on the second Thursday of September next in their respective religious congregations to render Him thanks for the many blessings He has bestowed on the people of the United States; that He has blessed them with a land capable of yielding all the necessaries and requisites of human life, with ample means for convenient exchanges with foreign countries; that He has blessed the labors employed in its cultivation and improvement; that He is now blessing the exertions to extend and establish the arts and manufactures which will secure within ourselves supplies too important to remain dependent on the precarious policy or the peaceable dispositions of other nations, and particularly that He has blessed the United States with a political Constitution rounded on the will and authority of the whole people and guaranteeing to each individual security, not only of his person and his property, but of those sacred rights of conscience so essential to his present happiness and so dear to his future hopes; that with those expressions of devout thankfulness be joined supplications to the same Almighty Power that He would look down with compassion on our infirmities; that He would pardon our manifold transgressions and awaken and strengthen in all the wholesome purposes of repentance and amendment; that in this season of trial and calamity He would preside in a particular manner over our public councils and inspire all citizens with a love of their country and with those fraternal affections and that mutual confidence which have so happy a tendency to make us safe at home and respected abroad; and that as He was graciously pleased heretofore to smile on our struggles against the attempts of the Government of the Empire of which these States then made a part to wrest from them the rights and privileges to which they were entitled in common with every other part and to raise them to the station of an independent and sovereign people, so He would now be pleased in like manner to bestow His blessing on our arms in resisting the hostile and persevering efforts of the same power to degrade us on the ocean, the common inheritance of all, from rights and immunities belonging and essential to the American people as a coequal member of the great community of independent nations; and that, inspiring our enemies with moderation, with justice, and with that spirit of reasonable accommodation which our country has continued to manifest, we may be enabled to beat our swords into plowshares and to enjoy in peace every man the fruits of his honest industry and the rewards of his lawful enterprise.

If the public homage of a people can ever be worthy the favorable regard of the Holy and Omniscient Being to whom it is addressed, it must be that in which those who join in it are guided only by their free choice, by the impulse of their hearts and the dictates of their consciences; and such a spectacle must be interesting to all Christian nations as proving that religion, that gift of Heaven for the good of man, freed from all coercive edicts, from that unhallowed connection with the powers of this world which corrupts religion into an instrument or an usurper of the policy of the state, and making no appeal but to reason, to the heart, and to the conscience, can spread its benign influence everywhere and can attract to the divine altar those freewill offerings of humble supplication, thanksgiving, and praise which alone can be acceptable to Him whom no hypocrisy can deceive and no forced sacrifices propitiate.

Upon these principles and with these views the good people of the United States are invited, in conformity with the resolution aforesaid, to dedicate the day above named to the religious solemnities therein recommended.

James Madison, Presidential Proclamation (November 16, 1814)

Prayer and Fasting

The two Houses of the National Legislature having, by a joint Resolution expressed their desire, that in the present time of public calamity and war, a day may be recommended to be observed by the people of the United States as a day of Public Humiliation and Fasting, and of Prayer to Almighty God, for the safety and welfare of these States, his blessing on their arms, and a speedy restoration of peace:

I have deemed it proper, by this Proclamation to recommend that Thursday the twelfth of January next be set apart as a day on which all may have an opportunity of voluntarily offering, at the same time, in their respective religious assemblies, their humble adoration to the Great Sovereign of the Universe, of confessing their sins and transgressions, and of strengthening their vows of repentance and amendment. They will be invited by the same solemn occasion to call to mind the distinguished favors conferred on the American people, in the general health which has been enjoyed, in the abundant fruits of the season; in the progress of the arts, instrumental to their comfort, their prosperity, and their security; and in the victories which have so powerfully contributed to the defense and protection of our Country; a devout thankfulness for all which ought to be mingled with their supplications to the Beneficent Parent of the human race, that He would be graciously pleased to pardon all their offences against Him; to support and animate them in the discharge of their respective duties; to continue to them the precious advantages flowing from political Institutions so auspicious to their safety against dangers from abroad, to their tranquility at home, and to their liberties, civil and religious; and that He would in a special manner, preside over the nation, in its public Councils and constituted authorities, giving wisdom to its measures and success to its arms, in maintaining its rights, and in overcoming all hostile designs and attempts against it; and finally, that by inspiring the Enemy with dispositions favorable to a just and reasonable peace, its blessings may be speedily and happily restored.

James Madison, Thanksgiving Proclamation (March 4, 1815)

The Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States, have, by a joint Resolution, signified their desire, that a day may be recommended, to be observed by the people of the United States with religious solemnity, as a day of thanksgiving and of devout acknowledgments to Almighty God, for his great goodness manifested in restoring to them, the blessing of peace.

No people ought to feel greater obligations to celebrate the goodness of the Great Disposer of events, and of the Destiny of Nations, than the people of the United States. His kind Providence originally conducted them, to one of [the] best portions of the dwelling place, allotted for the great family of the Human race. He protected and cherished them, under all the difficulties and trials to which they were exposed in their early days. Under His fostering care, their habits, their sentiments, and their pursuits, prepared them, for a transition in due time to a state of Independence and of self-Government. In the arduous struggle by which it was attained, they were distinguished by multiplied tokens of his benign interposition. During the interval which succeeded, he reared them into the strength, and endowed them with the resources, which have enabled them to assert their national rights, and to enhance their national character, in another arduous conflict, which is now happily terminated, by a peace and reconciliation with those who have been our Enemies. And to the same Divine Author of every good and perfect Gift, we are indebted for all those privileges and advantages, religious as well as civil, which are so richly enjoyed in this favored land.

It is for blessings, such as these, and more especially for the restoration of the blessing of peace, that I now recommend, that the second Thursday in April next be set apart, as a day on which the people of every religious denomination, may, in their solemn Assemblies, united their hearts and their voices, in a free will offering to their Heavenly Benefactor, of their homage of thanksgiving, and of their songs of praise.

Letters and Private Documents

James Madison, To William Bradford (November 9, 1772)1

You moralize so prettily that if I were to judge from some parts your letter…I should take you for an old Philosopher that had experienced the emptiness of Earthly Happiness…Yet however nice and cautious we may be in detecting the follies of mankind and framing our Economy according to the precepts of Wisdom and Religion I fancy there will commonly remain with us some latent expectation of obtaining more than ordinary Happiness and prosperity till we feel the convincing argument of actual disappointment.

Nevertheless a watchful eye must be kept on ourselves lest while we are building ideal monuments of Renown and Bliss here we neglect to have our names enrolled in the Annals of Heaven… 3 | 4

I think you made a judicious choice of history and the science of morals for your winter’s study. They seem to be of the most universal benefit to men of sense and taste in every post and must certainly be of great use to youth in settling the principles and refining the judgment as well as in enlarging knowledge and correcting the imagination. I doubt not but you design to season them with a little divinity now and then, which like the philosopher’s stone, in hands of a good man will turn them and every lawful acquirement into the nature of itself, and make them more precious than fine gold.

James Madison, To William Bradford (April 1, 1774)

[They (the House of Burgesses)] …are too much devoted to the ecclesiastical establishment to hear of the Toleration of Dissentients, I am apprehensive, [they] will be again made a pretext for rejecting their requests.

That liberal catholic and equitable way of thinking as to the rights of conscience, which is one of the characteristic of free people and so strongly marks the people of your province [Pennsylvania] is but little known among the zealous adherents to our hierarchy.

You are happy in dwelling in a land [Pennsylvania] where those inestimable privileges are fully enjoyed and the public has long felt the good effects of their religious as well as civil liberty…

I cannot help attributing those continual exertions of genius which appear among you to the inspiration of liberty and that love of fame and knowledge which always accompany it. Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise [and] every expanded prospect. How far this is the case with Virginia will more clearly appear when the ensuing trial is made.

James Madison, To William Bradford (January 24, 1774)

However political contests are necessary sometimes as well as military to afford exercise and practice and to instruct in the art of defending liberty and property.

Union of religious sentiments begets surprising confidence, and ecclesiastical establishments tend to great ignorance and corruption, all of which facilitate the execution of mischievous projects…

[U]nless you will glean instruction from their follies [various Kings of England] and fall more in love with liberty by beholding such detestable pictures of tyranny and cruelty…

[B]ut I begin to discover that they [excessive study of poetry, wit, romance plays, etc.] deserve but a moderate portion of a mortal’s time, and that something more substantial befits a riper age [Madison was 23 when he wrote this].

Equally absurd would it be for a scholar and man of business to make up his whole library with books of fancy and feed his mind with nothing but such luscious performances [excessive study of poetry, wit, romance plays, etc.]…

[B]ut [I] have nothing to brag of as to the state and liberty of my country [Virginia]. Poverty and luxury prevail among all sorts: pride ignorance and knavery among the priesthood and vice and wickedness among the laity…That diabolical Hell-conceived principle of persecution rages among some and to their eternal infamy the clergy can furnish their quota of imps for such business. This vexes me the most of anything whatever…So I leave you to pity me and pray for liberty of conscience to revive among us.

James Madison, Amendments to the Virginia Declaration of Rights (May 29-June 11, 1776)

The religion or the duty we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, being under the direction of reason and conviction only, not of violence of compulsion, all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of it according to the dictates of conscience…

[N]o man or class of men ought, on account of religion to be invested with peculiar emoluments [salaries] or privileges; nor subjected to any penalties or disabilities unless under etc.

[All men have the right to “enjoy the free exercise of religion…unpunished and unrestrained by the magistrate”] unless the preservation of equal liberty and the existence of the state are manifestly endangered; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

James Madison, To Thomas Jefferson (March 27/28, 1780)

[March 27] Among the various conjunctures of alarm and distress which have arisen in the course of the Revolution, it is with pain I affirm to you sir that no one can be singled out more truly critical than the present. Our army threatened with an immediate alternative of disbanding or living on free quarter; the public treasury empty; public credit exhausted, nay the private credit of purchasing agents employed, I am told, as far as it will bear, Congress complaining of the extortion of the people; the people of the improvidence of Congress, and the army of both; our affairs requiring the most mature and systematic measures, and the urgency of occasions admitting only of temporizing expedients, and those expedients generating new difficulties.

Believe me sir as things now stand, if the States do not vigorously proceed in collecting the old money and establishing funds for the credit of the new, that we are undone…

General Washington writes that a failure of bread has already commenced in the army, and that for anything he sees, it must unavoidably increase.

[March 28] [M]r. [John] Adams says it is the opinion of the most intelligent persons he had conversed with that the independence of the United States would be insisted on as a preliminary…

James Madison, To Thomas Jefferson (April 16, 1781)

The necessity of arming Congress with coercive powers arises from the shameful deficiency of some of the States which are most capable of yielding their apportioned supplies, and the military exactions to which others already exhausted by the enemy and our own troops are in consequence exposed. Without such powers too in the general government, the whole confederacy may be insulted and the most salutary measures frustrated by the most inconsiderable State in the Union.

The expediency however of making the proposed application to the States will depend on the probability of their complying If they should refuse, Congress will be in a worse situation than at present: for the confederation now stands, and according to the nature even of alliances much less intimate, there is an implied right of coercion against the delinquent party, and the exercise of by Congress whenever a palpable necessity occurs will probably be acquiesced in.

A navy so formed [as Madison described] and under the orders of the general Council of the States [Congress] would not only be a guard against aggression and insults from abroad. But without it, what is to protect the southern states for many years to come against the insults and aggressions of their northern brethren?

James Madison, To James Monroe (September 11, 1786)

Unless the sudden attendance of a much more respectable number takes place [at the Annapolis Convention] it is proposed to break up the meeting with a recommendation of another time and place, and an intimation of the expediency of extending the plan to other defects of the Confederation.

James Madison, To James Monroe (October 5, 1786)

There is no maxim in my opinion which is more liable to be misapplied, and which therefore more needs elucidation than the current one that the interest of the majority is the political standard of right and wrong. Taking the word “interest” as synonymous with “Ultimate happiness,” in which sense it is qualified with every necessary moral ingredient, the proposition is no doubt true. But taking it in the popular sense, as referring to immediate augmentation of property and wealth, nothing can be more false. In the latter sense it would be the interest of the majority in every community to despoil and enslave the minority of individuals; and in a federal community to make a similar sacrifice of the minority of the component States. In fact it is only reestablishing under another name and a more specious form, force as the measure of right…

James Madison, To Edmund Randolph (November 2, 1788)

The views of the greater part of the opposition to the Federal government, and particularly of its principal leader, have ever since the Convention been regarded by me as permanently hostile, and likely to produce every effort that might endanger or embarrass it.

His [Patrick Henry’s] enmity was leveled, as he did not scruple to insinuate against the whole system, and the destruction of the whole system I take to be still the secret wish of his heart, and the real object of his pursuit. If temperate and rational alterations only were his plan, is it conceivable that his coalition and patronage would be extended to men whose particular ideas on the subject must differ more from his own than those of others who share most liberally in his hatred?

My first wish is to see the government put into quiet and successful operation, and to afford any service that may be acceptable from me for that purpose. My second wish if that were to be consulted would prefer, for reasons formerly hinted, an opportunity of contributing that service in the House of Representatives rather than in the Senate, provided the opportunity be attainable from the spontaneous suffrage of the constituents.

I take it for certain that a clear majority of the Assembly [of Virginia] are enemies to the government [established by the Constitution], and I have no reason to suppose that I can be less obnoxious than others on the opposite side. An election into the Senate therefore can hardly come into question.

With these circumstances in view, it is impossible that I can be the dupe of false calculations, even if I were in other cases disposed to indulge in them. I trust it is equally impossible for the result, whatever it may be, to rob me of any reflections which enter into the internal fund of comfort and happiness. Popular favor or disfavor is no criterion of the character maintained with those whose esteem an honorable ambition must court. Much less can it be a criterion of that maintained with oneself. And when the spirit of party directs the public voice, it must be a little mind indeed that can suffer in its own estimation, or apprehend danger of suffering of that of others.

Mordecai M. Noah, To James Madison (May 6, 1818)

I take the liberty to enclose to you a Discourse delivered at the consecration of the Jewish Synagogue in this City, under the fullest persuasion, that it cannot but be gratifying to you, to perceive this portion of your fellow Citizens, enjoying an equality of privileges in this Country, and affording a proof to the world that they fully merit the rights they possess.

I ought not to conceal from you that it affords me Sincere pleasure, to have an opportunity of Saying, that to your efforts, and those of your illustrious Colleagues in the Convention, the Jews in the United States owe many of the blessings which they now enjoy, and the benefit of this liberal & just example, has been felt very generally abroad, & has created a Sincere attachment towards this Country, on the part of foreign Jews.

James Madison, Detached Memoranda: Religious Proclamations (c. January 31, 1820)

Madison Reflects on Religious Proclamations

They [the United States] have the noble merit of first unshackling the conscience from persecuting laws, and of establishing among religious Sects a legal equality. If some of the States have not embraced this just and this truly Xn [Christian] principle in its proper latitude, all of them present examples by which the most enlightened States of the old world may be instructed…

Ye States of America which retain in your Constitutions or Codes any aberration from the sacred principle of religious liberty, by giving to Caesar what belongs to God, or joining together what God has put asunder, hasten to revise your systems, and make the example of your Country as pure and complete, in what relates to the freedom of the mind and its allegiance to its maker, as in what belongs to the legitimate objects of political and civil institutions…

Religious proclamations by the Executive recommending thanksgivings and fasts are shoots from the same root with the legislative acts reviewed.

Although recommendations only, they imply a religious agency, making no part of the trust delegated to political rulers.

The objections to them are:

That governments ought not to interpose in relation to those subject to their authority but in cases where they can do it with effect. An advisory government is a contradiction in terms.

The members of a government as such can in no sense, be regarded as possessing an advisory trust from their Constituents in their religious capacities. They cannot form an Convocation, Council or Synod, and as such issue decrees or injunctions addressed to the faith or the Consciences of the people. In their individual capacities, as distinct from their official station, they might unite in recommendations of any sort whatever; in the same manner as any other individuals might do. But then their recommendations ought to express the true character from which they emanate.

They seem [to] imply and certainly nourish the erroneous idea of a national religion. This idea just as it related to the Jewish nation under a theocracy, having been improperly adopted by so many nations which have embraced Xnity [Christianity], is too apt to lurk [in] the bosoms even of Americans, who in general are aware of the distinction between religious and political societies. The idea also of a union of all who form one nation under one government in acts of devotion to the God of all is an imposing idea. But reason and the principles of the Xn [Christian] religion require that [if] all the individuals composing a nation were of the same precise creed and wished to unite in a universal act of religion at the same time, the union ought to be affected through the intervention of their religious not of their political representatives. In a nation composed of various sects, some alienated widely from others, and where no agreement could take place through the former, the interposition of the latter is doubly wrong.

The tendency of the practice, to narrow the recommendation to the standard of the predominant sect. The first Proclamation of General Washington dated January 1, 1795 recommending a day of thanksgiving, embraced all who believed in a supreme ruler of the Universe. That of Mr. Adams called for a Xn [Christian] worship. Many private letters reproached the Proclamations issued by J.M. [James Madison] for using the general terms, used in that of President Washington’s and some of them for not inserting particulars according with the faith of certain Xn [Christian] sects. The practice, if not strictly guarded, naturally terminates in a conformity to the creed of the majority and of a single sect, if amounting to a majority.

The last and not the least Objection is the liability of the practice, to subserviency [sic] to political views; to the scandal of religion, as well as the increase of party animosities.

James Madison, Detached Memoranda: Military Chaplains (c. January 31, 1820)

Madison Reflects on Chaplains in Congress and the Military

Is the appointment of Chaplains to the two Houses of Congress consistent with the Constitution, and with the pure principle of religious freedom?

In strictness the answer on both points must be in the negative. The Constitution of the U.S. forbids everything like an establishment of a national religion. The law appointing Chaplains [done by Congress in 1789] establishes a religious worship for the national representatives, to be performed by Ministers of religion, elected by a majority of them; and these are to be paid out of the national taxes. Does not this involve the principle of a national establishment, applicable to a provision for a religious worship for the Constituent as well as of the representative Body, approved by the majority, and conducted by Ministers of religion paid by the entire nation.

The establishment of the chaplainship to Congress is a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles. The tenets of the Chaplains elected shut the door of worship against the members whose creeds and consciences forbid a participation in that of the Majority. To say nothing of other sects, this is the case with that of Roman Catholics and Quakers who have always had members in one or both of the Legislative branches. Could a Catholic clergyman ever hope to be appointed a Chaplain? To say that [his] religious principles are obnoxious or that his sect is small, is to lift the veil at once and exhibit in its naked deformity the Doctrine that religious truth is to be tested by numbers, or that the major sects have a right to govern the minor.

If Religion consist in voluntary acts of individuals, singly, or voluntarily associated, and it be proper that public functionaries, as well as their constituents should discharge their religious duties, let them like their Constituents, do so at their own expense. How small a contribution from each member of Congress would suffice for the purpose? How just would it be in its principle? How noble in its exemplary sacrifice to the genius of the Constitution; and the divine right of conscience? Why should the expense of a religious worship for the Legislature, be paid by the public, more than that for the Executive or Judiciary branch of the government?

Were the establishment to be tried by its fruits, are not the daily devotions conducted by these legal Ecclesiastics, already degenerating into a scanty attendance, and a tiresome formality?

Rather than let this step beyond the landmarks of power have the effect of a legitimate precedent, it will be better to apply to it the aphorism de minimis non curat lex [“The law does not concern itself with trifles”]: or to class it cum maculis quas aut incuria fudit, aut humana parum cavit natura [“I shall not take offence at a few blots which a careless hand has let drop, or human frailty has failed to avert”].

Better also to disarm in the same way the precedent of Chaplainships [sic] for the army and navy, than erect it into a political authority in matters of religion. The object of this establishment is seducing; the motive to it is laudable. But is it not safer to adhere to a right principle, and trust to its consequences, than confide in the reasoning however specious in favor of a wrong one. Look through the armies and navies of the world, and say whether in the appointment of their ministers of religion, the spiritual interest of the flocks or the temporal interest of the Shepherds, be most in view: whether here, as elsewhere the political care of religion, is not a nominal more than a real aid. If the spirit of armies be devout, the spirit out of the armies will never be less so; and a failure of religious instruction and exhortation from a voluntary source within or without, will rarely happen: and if such be not the spirit of armies, the official services of their Teachers are not likely to produce it. It is more likely to flow from the labors of a spontaneous Zeal. The armies of the puritans had their appointed Chaplains, but without these there would have been no lack of public devotion in that devout age.

The case of navies with insulated crews may be less within the scope of these reflections. But it is not entirely so. The chance of a devout officer, might be of as much worth to religion, as the service of an ordinary chaplain. But we are always to keep in mind that it is safer to trust the consequences of a right principle, than reasonings in support of a bad one.

James Madison, To Jacob de la Motta (August, 1820)

Religious Liberty and the Jews

I have received your letter…with the Discourse delivered at the consecration of the Hebrew Synagogue at Savannah, for which you will please to accept my thanks.

The history of the Jews must forever be interesting. The modern part of it is at the same time so little generally known, that every ray of light on the subject has its value.

Among the features peculiar to the political system of the U. States, is the perfect equality of rights which it secures to every religious sect. And it is particularly pleasing to observe in the good citizenship of such as have been most distrusted and oppressed elsewhere, a happy illustration of the safety and success of this experiment of a just and benignant policy. Equal laws protecting equal rights are found as they ought to be presumed, the best guarantee of loyalty and love of country; as well as best calculated to cherish that mutual respect and good will among Citizens of every religious denomination, which are necessary to social harmony and most favorable to the advancement of truth. The account you give of the Jews of your Congregation brings them fully within the scope of these observations.

James Madison, To Nicholas P. Trist (July 6, 1826)

But we are more than consoled for the loss by the gain to him [speaking of Thomas Jefferson’s death]; and by the assurance that he lives and will live in the memory and gratitude of the wise and good, as a luminary of science, as a votary of liberty, as a model of patriotism, and as a benefactor of human kind.

In these characters I have known him [Thomas Jefferson], and not less in the virtues and charms of social life for a period of fifty years, during which there has not been an interruption or diminution of mutual confidence and cordial friendship for a single moment in a single instance.

James Madison, To Jared Sparks (April 8, 1831)

The finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris [Robert Morris]…A better choice could not have been made, as the performance of the task proved.

The knot felt as the Gordian [at the Constitutional Convention] was the question between the larger and smaller States on the rule of voting in the Senatorial branch of the legislature; the latter claiming, the former opposing, the rule of equality. Great zeal and pertinacity had been shown on both sides, and an equal division of the votes on the question had been reiterated and prolonged till it had become not only distressed but seriously alarming.

It was during that period of gloom that Dr. Franklin [Benjamin Franklin] made the proposition for a religious service in the Convention.

The tradition is, however, correct, that on the day of his resuming his seat [Robert Morris] he entered with anxious feelings into the debate, and in one of his speeches painted the consequences of an abortive result to the Convention in all the deep colors suited to the occasion.

James Madison, To Matthew Carey (July 27, 1831)

To trace the great causes of this state of things out of which these unhappy aberrations have sprung, in the effect of markets glutted with the products of the land, and with the land itself; to appeal to the nature of the Constitutional compact, as precluding a right in any one of the parties to renounce it at will, by giving to all an equal right to judge of its obligations…to make manifest the impossibility, as well as the injustice of executing the laws of the Union, particularly the laws of commerce, if even a single State be exempt from their operation; to lay open the effects of a withdrawal of a single State from the Union on the practical conditions and relations of the others, thrown apart by the intervention of a foreign nation; to expose the obvious, inevitable and disastrous consequences of a separation of the States, when into alien confederacies or individual nations; these are topics which present a task well worth the best efforts of the best friends of their country, and I hope you will have all the success which your extensive information and disinterred views merit.

If the States cannot live together in harmony under the auspices of such a government as exists, and in the midst of blessings such as have been the fruits of it, what is the prospect threatened by the abolition of a common government with all the rivalships, collisions, and animosities, inseparable from such an event?…[they would] quickly kindle the passions which are the forerunners of war.

James Madison, To Nicholas P. Trist (December 23, 1832)

There are in one of them [some newspapers from South Carolina that Trist had sent him] some interesting views of the doctrine of secession, one that had occurred to me, and which for the first time I have seen in print, namely that if on State can at will withdraw from the others, the others can at will withdraw from her, and turn her, nolentem [against his will], volentem [who wish], out of the Union. Until of late, there is not a State that would have abhorred such a doctrine more than South Carolina, or more dreaded an application of it to herself. The same may be said of the doctrine of nullification, which she now preaches as the only faith by which the Union can be saved.

I partake of the wonder that the men you name should view secession in the light mentioned. The essential difference between a free government and government not free is that the former is founded in compact, the parties to which are mutually and equally bound by it. Neither of them therefore can have a greater right to break off from the bargain than the other or others have to hold them to it. And certainly there is nothing in the Virginia Resolutions of 1798, adverse to this principle, which is that of common sense and common justice.

The fallacy which draws a different conclusion from them lies in confounding a single party, with the parties to the Constitutional compact of the United States…The former as one only of the parties owes fidelity to it till released by consent, or absolved by an intolerable abuse of the power created.

The Kentucky Resolutions being less guarded have been easily perverted.

But what can be more consistent with common sense than that all have the same rights, etc. should unite in contending for the security of them to each.

It is remarkable how closely the nullifiers who make the name of Mr. Jefferson [Thomas Jefferson] the pedestal for their colossal heresy, shut their eyes and lips, whenever his authority is ever so clearly and emphatically against them…It is high time that the claim to secede at will should be put down by the public opinion, and I shall be glad to see the task commenced by one who understands the subject.

James Madison, To William Cabell Rives (March 12, 1833)

[Referring to a speech by Rives] I have found as I expected that it takes a very able and enlightening view of its subject. I wish it may have the effect of reclaiming to the doctrine and language held by all from the birth of the Constitution, and till very lately by themselves, those who now contend that the States have never parted with an atom of their sovereignty, and consequently that the constitutional band which holds them together is a mere league or partnership without any of the characteristics of sovereignty or nationality.

It seems strange that it should be necessary to disprove this novel and nullifying doctrine, and stranger still that those who deny it should be denounced as innovators, heretics, and apostates. Our political system is admitted to be a new creation…Its character therefore must be sought within itself, not in precedents, because there are none…

What can be more preposterous than to say that the States as united are in no respect or degree a nation, which implies sovereignty, although acknowledge to be such by all other nations and sovereigns, and maintaining with them all the international relations of war and peace, treaties, commerce, etc. and, on the other hand and at the same time, to say that the States separately are completely nations and sovereigns, although they can separately neither speak nor harken to any other nation, nor maintain with it any of the international relations whatever and would be disowned as nations if presenting themselves in that character?

The nullifiers, it appears, endeavor to shelter themselves under a distinction between a delegation and a surrender of powers. But if the powers be attributes of sovereignty and nationality and the grant of them be perpetual, as I necessarily implied, where not otherwise expressed, sovereignty and nationality according to the extent of the grant are effectually transferred by it, and a dispute about the name is but a battle of words…The words of the Constitution are explicit, that the Constitution and laws of the US shall be supreme over the Constitution and laws of the several States [Constitution, Article VI, cl. 2]; supreme in their exposition and execution as well as in their authority.

The conduct of South Carolina has called forth not only the question of nullification, but the more formidable one of secession. It is asked whether a State, by resuming the sovereign form in which it entered the Union, may not of right withdraw from it at will. As this is a simple question whether a State, more than an individual, has a right to violate its engagements, it would seem that it might be safely left to answer itself.

One thing at least seems to be too clear to be questions, that while a State remains within the Union it cannot withdraw its citizens from the operation of the Constitution and laws of the Union. In the event of an actual secession without the consent of the co-States, the course to be pursued by these involves questions painful in the discussion of them.

[Referring to the Virginia Resolutions of 1798 and 1799] The doctrines combated are always a key to the arguments employed. It is but too common to read the expressions of a remote period through the modern meaning of them, and to omit guards against misconstruction [misinterpretation] not anticipated…The remark is equally applicable to the Constitution itself.

James Madison, Advice to my Country (1834)2

As this advice, if it ever see the light will not do it till I am no more it may be considered as issuing from the tomb, where truth alone can be respected, and the happiness of man alone consulted…

[W]ho [James Madison] espoused in his youth and adhered through his life to the cause of its liberty.

The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened; and the disguised one, as the Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise [Gen. 3].

James Madison, To George Tucker (June 22, 1836)

[I have great] confidence in your capacity to do justice to a character so interesting to his country and to the world [Thomas Jefferson].

I am, at the same time, justified by my consciousness in saying that an ardent zeal was always felt to make up for deficiencies in them [Madison’s services to the public] by a sincere and steadfast cooperation in promoting such a reconstruction of our political system as would provide for the permanent liberty and happiness of the United States.