Relevant Resources

- Quote Archive | The Papacy and the Invincibility of the Church

- Study Bank | The Ancient Lists and Testimonies of Popes Succeeding from Peter

Introduction

This is the first installment of a type of article we are calling “Papal Snapshots.” Each Papal Snapshot will present bite-size evidence for the papacy through stories, quotes, and documents from the ancient Church.

Roadmap

This “Papal Snapshot” concerns the acknowledgment of “the higher authority of the bishop of the Eternal City” by the pagan historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, relating to an event that took place in 355.

Our Roadmap is as follows:

- Our thesis is that this account provides good evidence that in the mid 4th century, the superior authority of the Pope was known not only to pagan historians, but Arian-friendly Roman emperors such as Constantius (who is mentioned by Ammianus). We will show this by:

- Providing historical context for the events described; then

- Quoting the account of Ammianus Marcellinus; then

- Summarizing the conclusions we believe can be reasonably inferred from this account.

Historical Context

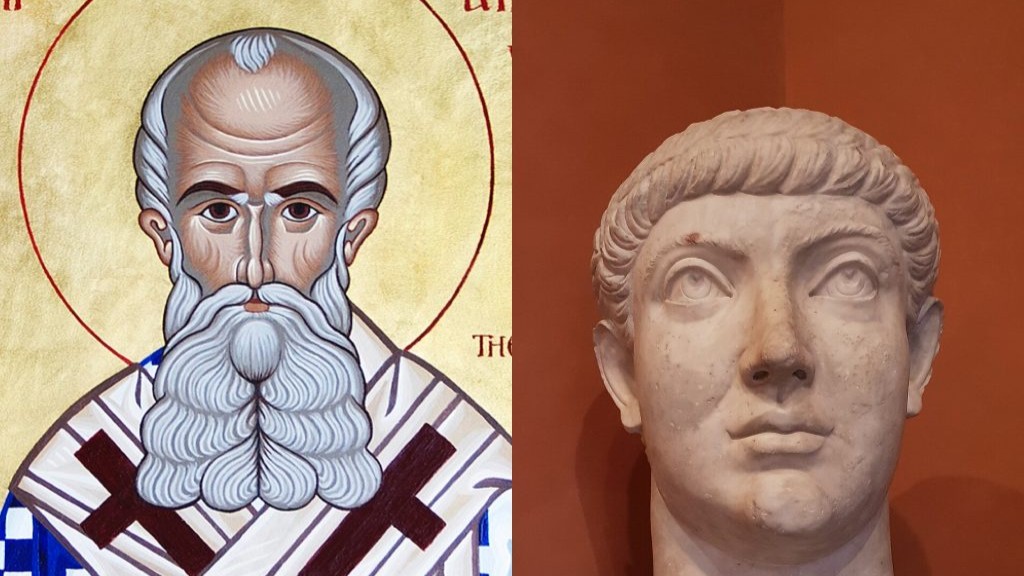

In the aftermath of the Council of Nicaea in 325, the doctrinal division between Catholics and the Arians continued to divide the Roman world. One of the greatest champions of the Nicene definition that affirmed the divinity of Christ was St. Athanasius of Alexandria. He was a constant target of Arian plots, and was exiled from his diocese at least five times.

By the time of the event recorded by Ammianus Marcellinus, St. Athanasius had been condemned by several eastern councils of bishops, including the Synod of Tyre in 335, and the Synod of Antioch in 341. The synod being referenced here is the Synod of Milan in 355, which was originally intended to be a general council like Nicaea, as Emperor Constantius—who was emperor of the entire empire, not just the west—desired to obtain doctrinal uniformity throughout the empire. After the synod, which was co-opted by Arians and condemned St. Athanasius, Constantius asked Pope Liberius to approve of the sentence against him. He refused, and in response the emperor banished him from Rome. The Church historian Sozomen also mentions the incident.1 St. Athanasius also discusses this and other incidents related to the persecution of Pope Liberius, and observed: “these impious men [the Arians] reasoned thus with themselves: ‘If we can persuade Liberius, we shall soon prevail over all.’”2

The Account of Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330-c. 390-400) was a pagan Roman historian of the 4th century. His work, Res gestae (“Things Done”), provides an interesting anecdote on the aforementioned historical events that sheds light on papal authority (Book 15, Ch. 7)3:

During Leontius’s administration [as prefect of Rome] Liberius [the Pope] the Christian bishop was summoned to appear before the imperial tribunal; his offense was resistance to the orders of the emperor and the decision of a majority of his brother bishops in a matter on which I will briefly touch. Athanasius, then bishop of Alexandria, who was persistently rumored to have thoughts above his station and to be prying into matters outside his province, had been deposed from his office by an assembly of the adherents of the same faith, meeting as what they call a synod. It was alleged that, being deeply versed in the interpretation of oracular sayings and of the flight of birds, he had on several occasions foretold the future events; he was also charged with other practices inconsistent with the principles of the faith of which he was a guardian. Liberius shared the views of his brethren, but when he was ordered by the emperor to sign the decree removing Athanasius from his priestly office he obstinately refused; he declared that it was entirely wrong to condemn a man unseen and unheard, and openly defied the emperor’s wishes. Constantius, who was always hostile to Athanasius, knew that the sentence had been carried out, but was extremely eager to have it confirmed by the higher authority of the bishop of the Eternal City. Failing in this object, he just managed to have Liberius deported under cover of night. This was a matter of great difficulty because of the strong affection in which he was held by the public at large.

Conclusions

From this anecdote, we can discern three facts relevant to papal authority:

- First, Ammianus, a pagan, was aware of the superior authority of the Pope, and reports it without any need to explain it.

- Second, Emperor Constantius, an ally of the Arians, was also aware of the superior authority of the Pope. Hence his attempt to co-opt Pope Liberius for Arian purposes.

- Finally, Ammianus’s reference to “the higher authority of the bishop of the Eternal City” means that both he and Constantius believed (or at least knew many Christians believed) that papal authority was superior to that of at least a synod of bishops, which in this case included—and was eventually co-opted by—bishops from the east. Constantius’s behavior subsequent to Liberius’s refusal to condemn St. Athanasius seems to confirm this.