Relevant Resources

Introduction

What is Purgatory, and is it taught in the Bible? Let’s talk about it, and yes.

This will be the first installment in our mini-series on Purgatory. Our hope is that non-Catholic Christians, especially protestants, will be willing to consider the many more Scriptural details that support the Catholic teaching about Purgatory after they see how clearly Jesus teaches it. Growing up protestant, I thought Purgatory was obviously unbiblical. But when I began reading the Church Fathers, and saw how they unpacked Scripture in such a way that Purgatory not only became plausible, but fairly obvious, I realized there was a much stronger biblical basis for this Catholic doctrine than I realized.

Roadmap

Our Roadmap for this installment is as follows:

- Our thesis is that Jesus teaches the doctrine of Purgatory quite clearly, despite the fact that many people miss it, including myself. I must thank Dr. Brant Pitre for pointing this out in his video, Purgatory in the Bible. We will obviously show this by diving into Christ’s words. But first, we’ll provide some important context for Purgatory that I think will be helpful for this and future installments. We’ll do this by:

- First, providing a brief definition of Purgatory (leaving various details for future installments); then

- Describing the human soul, and how it becomes “impure” through sin; then

- Explaining how sin results in both eternal and temporal punishment; then

- Showing how God exercises temporal punishment on His children to purify us of our sins and grow us in virtue (both in this life, and if necessary in Purgatory); then

- Providing a practical analogy to illustrate the common sense of Purgatory, what I call my “Punching a Hole in the Wall” story; and finally

- Reading Jesus’s Parable of the Faithful and Unfaithful Servants, recorded in Luke 12:41-48, and explaining how it clearly indicates something very much like the Catholic doctrine of Purgatory.

What is Purgatory? A Brief Definition

First, a brief definition of Purgatory. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (par. 1030) describes it this way:

All who die in God’s grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven.

The doctrine of Purgatory is quite basic, but has many details. For this introductory installment, we’ll stick with the basics.

The Catholic Church teaches that everyone, body and soul, will ultimately end up in either Heaven or Hell for all eternity. Only these two states are eternal.

However, She also teaches that some of those on the way to Heaven who have impurities in their soul will first be purged of those impurities prior to entering Heaven. Hence the word, “Purgatory.”

The Soul, Sin, and Impurities

Where do these impurities come from? From deliberate sins, and the just penalties due for those sins. We’ll explain this further, but if you keep in mind how a parent disciplines a child, you’ll understand the common sense basis of Purgatory much more easily.

To better understand this notion of “impurity” in our souls, let’s first clarify a few matters about the human soul. The soul, to use somewhat more technical language, is the form of the body. It’s what gives life to the body. This is why the definition of death is the separation of body and soul. Human beings possess what the Church calls a “rational soul,” which is a soul capable of knowing and obeying the truth (unlike animals). This is what it means to bear God’s image. God, who is Truth, created those who bear His image to know and love the Truth, which is ultimately Himself. We know the Truth with our minds. We love the Truth with our will.

The soul is therefore the seat of our two most basic powers as human beings: our intellect (by which we perceive the truth), and our will (by which we decide to obey or disobey the truth). Whenever we sin, we are in some sense discerning the truth with our intellect, but refusing to follow it with our will. This is why continuing to sin makes us more and more miserable. We are in some sense “splitting” our soul when we fail to keep our will aligned with our intellect, and fail to keep our intellect submitted to God (which is ultimately only possible by His grace).

When our intellect and will are severed by sin, this results in what Scripture and the Church often calls an “impurity” in our soul, which, in layman’s terms, means our soul is not perfectly aligned with God. It may know the Truth (with the intellect), but it is not loving the Truth (with the will). But to enter Heaven requires our intellect and will to be aligned with God, which is what it means to be “pure” or “clean” before God. Scripture is full of verses that speak of this purity required to be in God’s presence. One quick example of this comes from the book of the Apocalypse (“Revelation”), which says “Nothing unclean shall enter it [Heaven], nor anyone who practices abomination or falsehood, but only those who are written in the Lamb’s book of life” (Apoc. 21:27).

Eternal and Temporal Punishment

Such impurity in our souls, caused by sin, incurs two types of punishment: eternal (forever) and temporal (temporary). Eternal punishment is what is experienced in Hell. Temporal punishment is what is experienced in Purgatory (assuming we have not completed it in this life). Both punishments can be avoided by repentance, which, to speak in the terms we have been using, is realigning our intellect and will with God.

Eternal punishment is incurred when we fall into what Scripture calls mortal, or deadly sin, and fail to repent before death. The infinite punishment merited by such sin can only be paid for by Christ, whose grace not only cleanses us of our sins, but makes us new creatures, empowered to obey Him in love.

However, for those who have already been reborn in Christ, if we fall into sin and repent, our sin also incurs a temporal punishment, which God imposes on us so that we may grow in holiness. In terms of our intellect and will, true and salvific punishment is meant to help us realign both toward God, which, by sin, we allowed to fall away from Him by disobedience. That is why punishment is both painful, and necessary. As “good” as sin may have felt when we committed it, fully repenting of it in order to attain the holiness God intends for us will feel just as painful, if not more so. Robbing a bank of a million bucks feels “good.” Paying it back with interest is painful. But this is the only way our will, which was misaligned toward evil, can be realigned toward good. Once more, and as we will illustrate in a forthcoming example, think of a parent forgiving their child, but nonetheless imposing a disciplinary measure on them to help them grow in maturity. The parent’s desire is that by this growth in maturity, they will not only repair the damage they have done by their sin, but will grow in the virtue necessary to avoid repeating it. To speak again in terms of intellect and will, the parent’s punishment is meant to train the child to know the truth, and choose it with their will.

God treats us similarly through temporal punishments for our sin, which we can either pay in this life, or in the next. Any punishment left unpaid by someone who is otherwise in a state of friendship with Christ must still be paid, or “purged” from their souls, which happens after they die in Purgatory.

How the God Who Forgives Uses Punishment to Make Us Holy

We see this pattern of God using punishment to purify His children, those He loves, throughout Scripture, particularly in His relationship with King David. We will point to just two prominent examples.

First, in 1 Chronicles 21, King David violates God’s command that he not take a census of Israel. He repents of his sin, and asks God to remove his iniquity (v. 8). God responds by giving him three choices for a temporal punishment: a famine, a plague, or his defeat by his foes. Clearly in this case, God’s forgiveness of even “a man after His own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14) includes temporal punishment. But it is a completely different kind of punishment from the eternal punishment reserved for the wicked in Hell.

Similarly, after David committed adultery with Bathsheba, the prophet Nathan announced that God had forgiven his sin, but that he would nonetheless suffer a temporal punishment (2 Sam. 12:13-14):

And Nathan said to David, “The Lord also has put away your sin; you shall not die. 14 Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the Lord, the child that is born to you shall die.”

It was about this incident that King David wrote the famous Psalm 51 about repentance. Both the prophet Nathan, and David himself, are crystal clear that God has forgiven him, but that this forgiveness included a temporal punishment.

This shouldn’t surprise us, because Scripture is very clear in more general terms that God uses temporal punishment to grow His children in holiness. A good example would be Proverbs 3:11-12, which is quoted in Hebrews 12:5-6:

11 My son, do not despise the Lord’s discipline or be weary of his reproof, 12 for the Lord reproves him whom he loves, as a father the son in whom he delights.

First, it’s important to recognize that Scripture speaks of God imposing punishment and discipline on those He considers “sons,” those “whom he loves…in whom he delights.” These are those the Catechism refers to as “in God’s grace and friendship.” Therefore, we are not speaking of someone on their way to Hell, or outside the grace of Christ. We are speaking about those who are in a loving relationship with God, by God’s grace.

Second, Scripture speaks of God inflicting “discipline” and “reproof” on these sons “whom he loves.” Scripture explains the purpose of this as follows (Heb. 12:7-11):

7 It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons; for what son is there whom his father does not discipline? 8 If you are left without discipline, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons. 9 Besides this, we have had earthly fathers to discipline us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? 10 For they disciplined us for a short time at their pleasure, but he disciplines us for our good, that we may share his holiness. 11 For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant; later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.

We see quite clearly that God reserves a painful form of discipline exclusively for his legitimate children. Clearly, this reality is present in both the Old and New Testaments. However, this punishment—unlike the eternal punishment of Hell—is meant to make them holy, and its ultimate fruit is the righteousness necessary to obtain eternal life in Heaven.

That is why the Catholic Church teaches that God, in love, applies this form of discipline to every Christian who commits sin after receiving baptism (which cleanses their souls, and makes them a new creature, in a state of grace and friendship with God). The purpose is to purify their souls of the sins they have committed after baptism, and lead them to eternal life in Heaven.

However, if they die before their discipline has been completed, their soul is not yet completely purified. They have not yet fully realigned their will to God, which the punishment is intended to help them do. So the place where their soul receives this final purification and discipline, this final realignment of their will toward God before Heaven is Purgatory.

As the book of Hebrews states quite clearly, this discipline is only applied to God’s legitimate children, and it results in greater righteousness, which is precisely what the Catechism teaches about Purgatory: it is only for those who are on their way to Heaven (being legitimate children), and will result in them being purified (and therefore, more righteous).

This is not a concoction of the Catholic Church. It’s not only all over Scripture, but it’s a reality every parent is well aware of. They punish their children to help them become better. This punishment, as Scripture quite clearly says, is not a negation of God’s mercy, somehow done outside of or apart from it. Rather, it is an exercise of God’s mercy, specially reserved for those He loves, and who love Him.

Here is an example to illustrate the concept.

Punching a Hole in the Wall

Now we arrive at the analogical story I promised at the beginning.

Let’s say a Christian purposely punches a hole in someone’s wall. This is a serious sin. Unless they repent, they are on their way to Hell, because they deliberately chose hatred of their neighbor, which breaks Jesus’s commandment to love our neighbors as ourselves.

But let’s say they repent. Now, they are no longer threatened with Hell. Eternal punishment is off the table because they have turned back to God.

However, their neighbor’s wall still has a hole in it. Therefore, in justice, they are obligated to repair the wall that they broke by their sin. This is part of the temporal punishment they owe because of their sin.

Imagine the Christian in this case was a teenager. The person whose wall they broke could forgive them, and their earthly father could forgive them. But despite being forgiven, any earthly father worth their salt will punish them. They will require their child to repair the damage they have done. In justice, the hole in the wall must be fixed. They can do so in many different ways: they can ground them, deduct money from their allowance, require them to buy the supplies and fix it themselves, etc.

This punishment is temporary, not eternal. But it must be done. Does their father do this because he hates them, or because their relationship is broken, or because his forgiveness is not sufficient? No, of course not. He does it because he loves them, and wants them to grow in virtuous maturity—exactly as Scripture describes God’s desire for His children. A good father desires his child to have a pure soul, which means the split between their intellect and will that took place when they punched the hole in the wall must be healed. They bring their intellect and will back together by repairing that damage, for just as they chose with their will to create the hole, they must now likewise choose with their will to repair it. This healing is the result of their submission to their father’s love through punishment. This is why protestant accusations that Catholics believe in “works based salvation” when it comes to the doctrine of Purgatory stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what Purgatory is all about. It is as incoherent as accusing a child who is willingly and dutifully bearing a punishment imposed on them by a loving parent of thinking they “deserve” their parent’s mercy by bearing the punishment, or that this punishment is once more somehow outside of, or separate from, the parent’s love and grace.

At this point, there are two possible outcomes:

- The repentant teenager repairs the temporal damage from punching a hole in their neighbor’s wall in this life; or

- If they die before doing so, they will pay for that temporal damage in the next life, prior to entering Heaven.

It’s that simple, and the “place” where this final disciplinary cleansing unto righteousness occurs is Purgatory.

Jesus Teaches the Doctrine of Purgatory in a Parable (Luke 12:41-48)

This gets us to the place in the Gospels where Jesus quite explicitly teaches that some Christians will undergo temporal punishment prior to entering Heaven.

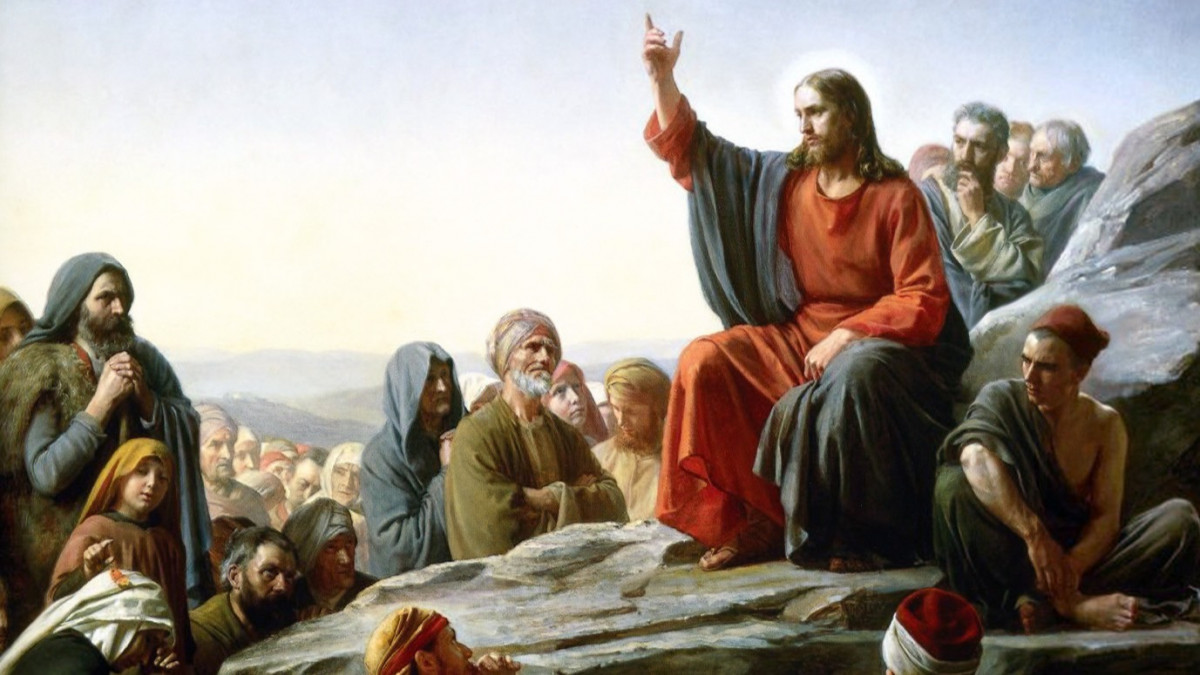

He does so in His Parable of the Faithful and Unfaithful Servants, where we read as follows (Luke 12:41-48):

41 Peter said, “Lord, are you telling this parable for us or for all?” 42 And the Lord said, “Who then is the faithful and wise steward, whom his master will set over his household, to give them their portion of food at the proper time? 43 Blessed is that servant whom his master when he comes will find so doing. 44 Truly, I tell you, he will set him over all his possessions. 45 But if that servant says to himself, ‘My master is delayed in coming,’ and begins to beat the menservants and the maidservants, and to eat and drink and get drunk, 46 the master of that servant will come on a day when he does not expect him and at an hour he does not know, and will punish him, and put him with the unfaithful. 47 And that servant who knew his master’s will, but did not make ready or act according to his will, shall receive a severe beating. 48 But he who did not know, and did what deserved a beating, shall receive a light beating. Everyone to whom much is given, of him will much be required; and of him to whom men commit much they will demand the more.

In His parables, Jesus frequently uses the metaphor of a master imparting a gift to his servants, and later judging them according to how they managed them, in such a way that we know He is often talking about the Day of Judgment. We see this, for example, in the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant (Matt. 18:23-35), where the master forgives his servant, expects him to forgive others, but when he doesn’t, the master returns and punishes him accordingly. We also see it in the Parable of the Wicked Tenants (Matt. 21:33-46; Mark 12:1-12; Luke 20:9-19) where the master leaves his vineyard to his servants, and later returns and punishes them for how they treat his messengers (and ultimately his son). Likewise, in the Parable of the Talents (Matt. 25:14-30), the master hires servants, and when he returns, they each receive a different reward or punishment based on what they did.

There are other examples, but these suffice to illustrate the pattern.

Christ utilizes this same metaphor in the Parable of the Faithful and Unfaithful Servants we just read. However, He doesn’t mention only two outcomes—namely Heaven and Hell. Rather, He describes four (really three), which are as follows:

(1) Eternal reward—Heaven

“Blessed is that servant whom his master when he comes will find so doing. Truly, I tell you, he will set him over all his possessions” (vv. 43-44).

(2) Eternal punishment—Hell

“[The master] will punish him, and put him with the unfaithful” (v. 46).

(3A) Temporary (severe) punishment—Purgatory

“[The servant] shall receive a severe beating” (v. 47).

(3B) Temporary (light) light punishment—Purgatory

“[The servant] shall receive a light beating” (v. 48).

Thus, Jesus clearly describes three types of outcomes for the master’s servants. Each of these describes what the servants receive upon the master’s return (i.e. Christ’s return), and are thus clearly eschatological. There is no more work to be done. All that remains is reward and punishment.

Two of the outcomes are eternal, obviously corresponding with Heaven and Hell (#1 and #2). However, one of the outcomes clearly refers to temporary punishment, whether severe or light (#3A-B). This would likewise obviously correspond with Purgatory. And since temporary punishment excludes the possibility of Hell (since Hell is eternal), it logically follows that after death, some who are in a state of friendship with Christ will in fact attain eternal life in Heaven, but only after receiving some sort of temporal punishment by which they are cleansed.

In other words, they will go through exactly what the Church describes as Purgatory.

So there it is: Purgatory straight from the mouth of Christ.