Introduction

There are few parts of the Bible that played a bigger role in bringing me to the Catholic Church than Acts 15—the account of the “Council of Jerusalem.” There is a reason this article is among the longer articles of Becoming Catholic—it takes a good deal of unpacking. Even now, I feel there is more to say. But I believe the points made below will potentially be very illuminating for many, so I welcome you on this most unlikely and unexpected journey of discovery.

Roadmap

Our Roadmap is as follows:

- Our thesis is that the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 illustrates a fundamentally Catholic framework of Church authority. We will show this by:

- Explaining our early doubts as a protestant about Acts 15 and the Council of Jerusalem, failing to understand how it could apply to our protestant paradigm; then

- Examining my preliminary question at the time, namely “Why did the Apostles have to resolve a theological issue?”; then

- Showing how the Council of Jerusalem acted in a manner that was Catholic, authoritative, infallible, apostolic, and hierarchical; then

- Showing how St. Peter’s role in the Council of Jerusalem was very papal, drawing from typology in the Old Testament, evidence from the New Testament, and the interpretations of various Church Fathers, both east and west; followed by

- A summary of my conclusions in answer to the question that haunted me as a protestant: “Where is that Church today?”

Early Doubts

When I was a teenager, I remember re-reading Acts, and being struck by this chapter. I had heard about the ancient Church Councils, and this seemed to be the prototype for those.

But more fundamentally, I was struck by something which, to me, seemed very odd: the Apostles had to resolve a theological issue. This didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me. Didn’t they receive the whole faith directly from Christ? What possible issues could they have to fix? Wasn’t it the Faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3)?

This invariably led me to a host of other questions, the pondering of which caused me to have deep doubts about the protestant paradigm. This all happened long before becoming Catholic was even on the horizon—indeed, the very thought would have horrified me at this early stage.

The various issues I struggled through were as follows:

- If the faith was “one for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3), how is it possible that even the Apostles had a theological issue that needed to be resolved?

- Why was the Council’s decision not directly based on Scripture, but the authority of the Apostles, those they appointed, and the Holy Spirit?

- Why was the Council’s decision binding on all local churches? What if they interpreted Scripture differently? I thought the local church was the primary locus of church authority?

- Why did the Apostles involve the leaders they had appointed in the decision? Wasn’t their own authority sufficient?

- What about what I would later call “the Logistical Issue,” meaning—was the Council’s decision binding when it written, or only after Luke included it in the Bible when he wrote the book of Acts? If it was binding before it was included in the Bible, that would seem to have implications for the protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. But if it was binding only afterward, then that made the Apostles and the other leaders of the Church involved in the decision stunningly presumptuous.

As a protestant, I simply had no coherent way to explain something like the Council of Jerusalem. Despite the claims of this sect or that denomination to having a “biblical” church, none of them had anything remotely comparable to the Council of Jerusalem with which to definitively resolve theological issues, and authoritatively differentiate dogma (an “essential” of the Faith) from mere opinion (things we can have good faith disagreements about), let alone for all Christians.

In short, I found myself constantly asking myself, when reading Acts 15, “where is that Church today?” Surely, if we were to be biblical, such a Church must exist!

But before I delve into the answers I eventually arrived at, I want to briefly address the question that initiated all this: why did the Apostles have to resolve a theological issue at all, despite already having the Faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3)?

Preliminary Question: Why did the Apostles have to resolve a theological issue?

This was the question that started it all: how could the men who spent three years with Jesus, and had the Faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3) need to resolve a theological issue?

Indeed, I had often heard Jude’s words used to buttress the doctrine of sola scriptura—the Faith, in the time of the Apostles, was final, and finalized. But the Council of Jerusalem seemed to imply something else: that the Faith, while complete, requires elaboration as new questions arise. And when such resolutions are required, the final say is rendered by a living authority.

In this case, the question was relatively straightforward: do baptized Christians need to also be circumcised, and follow the law of Moses? Luke described the commotion caused by those who raised this question, the “Judaizers” (Acts 15:1-2):

But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brethren, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.” And when Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the Apostles and the elders about this question.

There was a theological question/issue on the table, and while Paul and Barnabas believed the Judaizers were in error, it seemed that a definitive resolution was required. As far as Scripture is concerned, Jesus never said anything definitive about this issue, nor had the Apostles prior to the Council. And—very oddly for someone like myself who was taught sola scriptura—it seemed that everyone was assuming that a definitive decision could only be rendered by a living authority. They didn’t say “let’s attempt to interpret Scripture for ourselves on this point.” They didn’t even appeal to the apostolic authority of Paul himself, but rather to a decision by a seemingly higher authority—the living authority of the Church as a whole.

Apparently this issue was uncertain even among believers. As Luke records a few verses later, when Paul and Barnabas arrived in Jerusalem, “some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up, and said, ‘It is necessary to circumcise them, and to charge them to keep the law of Moses’” (Acts 15:5). So while the men that “came down from Judea” were not explicitly described as believers (perhaps they were, but we don’t know for sure), those in Jerusalem were described as believers.

To be clear: I’m not saying this necessarily means there was ubiquitous confusion on this point of doctrine. Paul and Barnabas, after all, seemed to be quite aware that the Judaizers were in error. But, as Luke makes clear, their error was shared by other believers as well.

So this is not a case of coming up with new doctrine out of whole cloth. Rather, as has happened often in Church history, what had been understood implicitly required an explicit formulation in response to challenges, in this case, from the Judaizers. In other words, doctrine develops and becomes clearer (and deeper) in response to challenges. A single seed contains all the material of the mighty tree that comes from it—and yet they are still the same thing. The tree is just an unpacking and growth of everything that was in the seed. Jesus Himself described the Kingdom of Heaven in this way when He compared it to a mustard seed (see Matt. 13:31-32). We all know this as individuals, and the same is true for the Church—we can have all the material of the Faith, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we have unpacked it in all its glory. To do so requires time, maturation, and deep prayer and thought. As with individuals, so with the Church: challenges are a time for refinement, and pruning. In the process, our faith becomes deeper and better understood. This process of development was widely known and accepted by the Church Fathers, since it was understood not as a changing of the Faith, but as an unpacking of the Faith.

Here are a few examples of the acceptance of the idea of development of doctrine among the Church Fathers. The first is from St. Augustine’s City of God (Book 16, Ch. 2), written in the early 400’s:

For while the hot restlessness of heretics stirs questions about many articles of the Catholic faith, the necessity of defending them forces us both to investigate them more accurately, to understand them more clearly, and to proclaim them more earnestly; and the question mooted by an adversary becomes the occasion of instruction.

In AD 412, St. Augustine wrote elsewhere (Epistle 137, §16):

Heresies bud forth against the name of Christ, though veiling themselves under His name, as had been foretold, by which the doctrine of the holy religion is tested and developed.

Another example comes from one of St. Pope Gregory the Great’s Epistles (Book VIII, Letter 2), written around the end of the 500’s:

Moreover, there is this by the great favor of Almighty God; that among those who are divided from the doctrine of Holy Church there is no unity, since every kingdom divided against itself shall not stand [Luke 11]. And holy Church is always more thoroughly equipped in her teaching when assaulted by the questionings of heretics; so that what was said by the Psalmist concerning God against heretics is fulfilled, ‘They are divided from the wrath of his countenance, and his heart has drawn near’ [Ps. 55:20-21]. For while they are divided in their wicked error, God brings His heart near to us, because, being taught by contradictions, we more thoroughly learn to understand Him.

We see this process in action both prior to, and at the Council of Jerusalem. An issue was dividing the Church, and required a resolution. In resolving it, the Church would arrive at an even deeper understanding of the Faith.

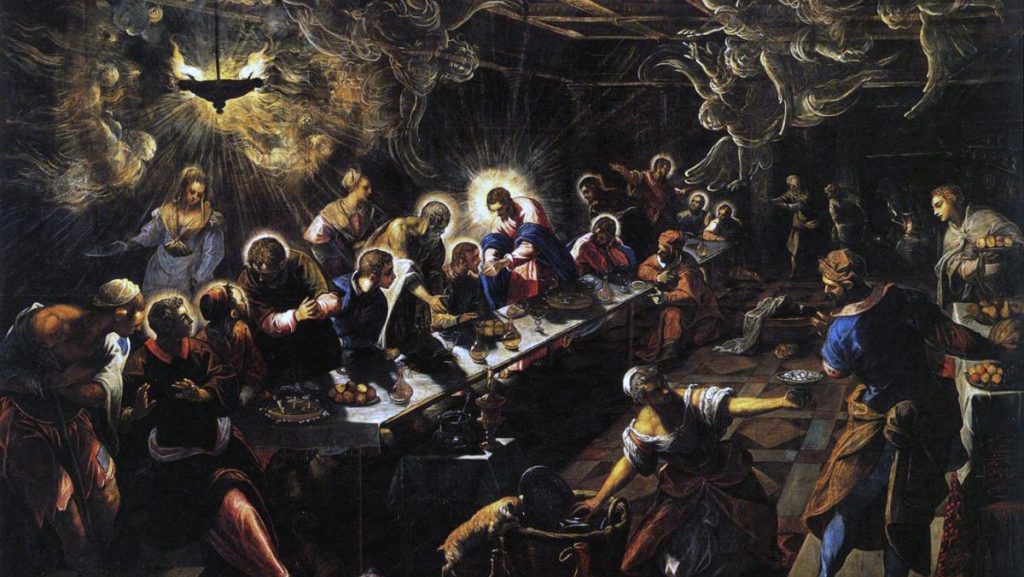

So did everyone decide to get out their Bibles and begin debating in their local congregations? No. Rather, they took part in the first Church Council, whose proceedings are recorded in Acts 15, and whose purpose was to render a definitive answer to this theological question.

Realizing this was very troubling for me, as I knew of no such mechanism as a protestant. I was always told that being protestant was “biblical,” and that everything we did had to be based on the Bible. And yet, here I was, seeing the earliest Christians take for granted a method of resolving theological controversies in a definitive way that was nowhere present among my fellow protestants—an appeal to a living authority, possessed of divine authority, that was empowered to resolve, once and for all, theological controversies.

It seemed that the Bible took for granted that the Faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3) would gradually unfold and become ever more glorious as new questions arose, and the Church was able to authoritatively answer those questions.

Where is that Church today? That question haunted me. Pondering it eventually led me to the Catholic Church. Along the way, and even before deciding to convert, I arrived at five realizations about the Council of Jerusalem and its decisions. I realized they were:

- CATHOLIC—the Council’s decisions applied to the whole Church, and thus all local churches, making it universal, or Catholic;

- AUTHORITATIVE—the Council’s decision was Catholic by virtue of its being authoritative, meaning they had the divine authority to render it, and all Christians/local churches had a divinely-imposed obligation to obey it;

- INFALLIBLE—the Council’s decision was Catholic, and authoritative by virtue of its being infallible, or without error;

- APOSTOLIC—the Council’s decision was Catholic, authoritative, and infallible by virtue of its being Apostolic, or rendered by Christ’s “sent ones” (the Apostles), as well as those they themselves sent/appointed (non-Apostles exercising Apostolic authority);

- HIERARCHICAL—the Council’s decision was exercised in accordance with a hierarchical structure of Church government, with authority being exercised by (in ascending order) the elders, the Apostles, and the Chief Apostle, Peter.

With that, I’ll unpack each one.

(1) CATHOLIC

The Council’s decisions applied to the whole Church, and thus all local churches, making it universal, or Catholic.

While this is implied prior to the Council, as well as by the fact that the Council made decisions about “the Gentiles,” it becomes explicit in Acts 16, when Paul and his entourage deliver the Council’s decision to all the local churches (Acts 16:1-5):

As they [Paul, Silas, and Timothy] went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the Apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem. So the churches were strengthened in the faith, and they increased in numbers daily.

The first thing I noticed was that Paul himself was apparently not a sufficient authority on this matter. Indeed, if he had been, he would not have been deputized to attend the Council at the beginning of Acts 15. This issue required the decision of “the Apostles and the elders.” Naturally, this doesn’t derogate from Paul’s individual Apostleship. Rather, it places it within a larger collective consisting of the Apostles, and those they had appointed, “the elders.”

Thus, the only conclusion I could draw was that Paul himself was part of, but also under an authority higher than his own individual apostolic authority. To me, this implied that the Church possessed a competent universal authority to render certain decisions that would be binding on all Christians and individual churches.

And that is precisely what we see in Acts 16 when the Council’s decision was delivered to all the local churches “for observance.” The Council clearly understood itself to be the competent catholic authority over all local churches.

If this was the case, then local churches could not be entirely self-governing. The Church Universal, the Catholic Church, possessed superior authority. And here, the Council clearly understood itself to be that catholic authority, and the local churches were bound by its decisions.

We don’t see a single example of any local church presuming to disagree with or defy the Church, for indeed local authority could not countermand catholic authority. If it could, then it would have been silly for Paul to presume to deliver a letter from a far-off Council to local churches “for observance.”

As a protestant, I had no framework to grapple with this fundamental biblical reality: the early Church had a catholic authority. It wasn’t a series of autonomous local churches arriving at their own decisions on doctrine. Nor was it a set of various denominational alliances arriving at their own decisions on doctrine. No—the early Church, while obviously consisting (as the Church does today) of local bodies, was nonetheless one, universal body, and thus had a universal, or catholic means of governing itself. There was simply no way I could square this with any form of protestant church government—congregationalist, presbyterian, independent, denominational, etc. None of them fit.

This catholic decision, however, was all the more fascinating because not only did the Council claim to have catholic authority, but even more importantly, it claimed to have divine authority. That brought me to my second realization.

(2) AUTHORITATIVE

The Council’s decision was Catholic by virtue of its being authoritative, meaning they had the divine authority to render it, and all Christians/local churches had a divinely-imposed obligation to obey it.

The letter containing the Council’s decision read as follows (Acts 15:23-29):

The brethren, both the Apostles and the elders, to the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch and Syria and Cilicia [all the places that had churches], greeting. Since we have heard that some persons from us have troubled you with words, unsettling your minds, although we gave them no instructions, it has seemed good to us in assembly to choose men and send them to you with our beloved Barnabas and Paul, men who have risked their lives for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ. We have therefore sent Judas and Silas, who themselves will tell you the same things by word of mouth. For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell.

What was impossible to miss in the Council’s letter, especially for someone from my protestant background, was the total lack of any direct citation of Scripture. In fact, not only is Scripture not cited, but other sources of authority are—namely, the authority of the Apostles and elders, as well as the Holy Spirit Himself! If Scripture was the sole infallible rule of Faith for the Church, how could it be totally absent from the Council’s letter? Yes, the Council refers to various precepts of the Mosaic law, but the substance of their decision contains no such citation to Scripture—why did only these provisions of the Mosaic law continue to apply? Why not others? And where does Scripture say so? Such questions are in fact totally absent, it seemed, from the Council’s thinking. They had the authority to establish these things, and that authority came from God Himself.

Notice what the Council says: that it had the authority to impose “burdens” on believers, and that complying with such burdens was “necessary.” The Council believed it had the authority to issue a binding decision, and it did so without directly appealing to Scripture. Rather, it merely observed that its decision was compatible with Scripture. It never pretends that it directly flows from it.

In fact, the only time Scripture is directly cited is by James during the Council (not in its letter) after he affirms Peter’s decision. He cites the prophet Amos (Acts 15:16-18):

‘After this I will return,

and I will rebuild the dwelling of David, which has fallen;

I will rebuild its ruins,

and I will set it up,

that the rest of men may seek the Lord,

and all the Gentiles who are called by my name,

says the Lord, who has made these things known from of old’ (Amos 9:11-12).

Indeed, the verses of Amos cited by James said nothing about circumcision, and nothing about the specific contents of the Council’s ruling on which parts of the Mosaic law would continue to be obligatory for Gentiles.

Adding yet another layer of perplexity to my protestant mind, I realized that the decision they rendered could not flow directly from Scripture, for the overwhelming scriptural evidence in existence at that time (virtually none of the New Testament had been written yet) would have prescribed circumcision and the rest of the Mosaic law. There wasn’t a single verse that explicitly required the details which the Council included in its decision.

I often heard from my more intellectually and theologically rigorous protestant friends (typically of the reformed variety) about the importance of exegesis, a method by which they claimed all doctrine could be arrived at by properly unpacking the text of Scripture.

But that is precisely what was impossible to do here: there was no part of Scripture which specifically required, or, without already knowing the Council’s decision, would have necessitated the specifics of that decision. What part of the Scripture existing at that time spoke of baptism? What part spoke of only certain parts of the Mosaic law applying to Gentiles? Even Jesus wasn’t very explicit about that. In fact, He said things that could more easily be construed in the opposite direction. Yes, Amos was cited by James at the end of the Council, and Amos describes the coming in of the Gentiles. But beyond that general idea, the Bible as it existed at that time could not have provided the material substance of the Council’s decision. Interpretation based on an already existing Tradition, or teaching, was required. That was the reason those who issued the decision appealed to both their, and the Holy Spirit’s authority. Exegesis would have gotten them nowhere. This was another strike at not only the notion of sola Scriptura, but the protestant paradigm as a whole.

This led me to consider what I earlier called “the Logistical Issue.” What do I mean by this? This is an issue I have never heard raised by any other person. Indeed, a Catholic friend of mine (who is also a convert), when I raised this argument, was deeply struck by it, and said he had never heard it before either.

Essentially it amounts to this: clearly Luke is writing the book of Acts about events that have already taken place. Acts 15 contains the text of a letter written by the Council. But this raised a very disconcerting question for me. In that letter, the basis for the decision was the authority of both the Apostles/elders, and the Holy Spirit. This made the contents of the letter binding on all Christians as if delivered by God Himself. And yet, this letter was not Scripture. It would one day be included in Scripture, but it was not Scripture yet. And yet no one seemed to object to its authority being considered divine. Even more concerning for me was the fact that the Council considered its decision binding whether it was written down or not! Its letter says, after all (Acts 15:27):

We have therefore sent Judas and Silas, who themselves will tell you the same things by word of mouth.

As someone raised on sola Scriptura, I was thus confronted with a very unsettling reality: the Council’s decision was believed to have been divinely binding despite the fact that it was delivered in a letter that was not yet part of Scripture, that didn’t appeal to Scripture, appeals to the authority of the Apostles/elders and the Holy Spirit (and thus divine authority), and which was valid whether delivered in writing, or by word of mouth.

To maintain my adherence to sola Scriptura (Scripture as the only divine and infallible source of doctrine in the Church) I thus asked myself a very uncomfortable question: was the decision of this Council binding when it was written/delivered, or only after it was included in Scripture?

This brought me to an impasse that ultimately caused me to abandon sola Scriptura (though this was not the only reason I did so), and for the first time open my mind to the possibility of an authoritative (having divine authority) Church. The only two alternatives available were simply absurd, and made the Christian faith ridiculous if protestant premises were accurate:

1. The Council’s decision was not binding at the time it was made (because not in Scripture).

2. The Council’s decision was binding at the time it was made (despite not being in Scripture yet), whether delivered in writing or by word of mouth.

The first was deeply disturbing, for it made the Apostles/elders charlatans given that they claimed to have the authority of the Holy Spirit to render such a decision.

The second was the only possible option. But this was, likewise, deeply disturbing, for it meant that there was a Church that had divine authority to render judgments on doctrinal and disciplinary matters, all without any direct appeal to, or citation of, Scripture (though clearly it understood its decisions to be compatible with Scripture, even if they didn’t directly flow from it), and whether those decisions were delivered in writing or by word of mouth. In other words, even if the Council’s letter had not ended up in Scripture, they believed their decision remained binding on all Christians, because it was rendered with divine authority.

But, in one last ditch effort to rescue sola Scriptura, I told myself that even if the Council’s decision was binding at the time it was made, rather than only after it was included in Scripture, surely Scripture itself would resolve the problem by telling me when this supposedly authoritative Church ceased to exist.

But that is something Scripture never does. It exhibits the reality of an authoritative Church. However, it never states, nor does it ever imply, that such an authoritative Church ceases to exist, or will ever cease to exist, at a later point in time. But that’s precisely what I needed it to say if in fact sola Scriptura was true—the only way I could deny the possibility of an authoritative Church continuing to exist is if Scripture told me it had, or would, cease to do so.

But Scripture never did.

I was thus led to my third realization.

(3) INFALLIBLE

The Council’s decision was Catholic, and authoritative, by virtue of its being infallible, or without error.

The Council delivered a decision that it not only ascribed to the leaders who wrote its letter (the Apostles and the elders they had appointed), but also the Holy Spirit. In short, we see not just Apostles, but those they appointed, and the Holy Spirit, all working in tandem. The result? A decision on Christian teaching that was infallible, or without error.

I realized that to arrive at any other conclusion would lead to absurd conclusions. The decision had to have been without error (infallible); it was infallible by virtue of its divine authority; and therefore, the early Church exercised an infallible authority that Scripture itself provided no indication had ever, or would ever cease (prior to Christ’s return).

I knew of only one Church who continued to make such a claim for itself.

This led to the fourth realization.

(4) APOSTOLIC

The Council’s decision was Catholic, authoritative, and infallible by virtue of its being Apostolic, or rendered by Christ’s “sent ones” (the Apostles), as well as those they themselves sent/appointed (non-Apostles exercising Apostolic authority).

We see in Acts 15 who the authority is: “the Apostles and the elders.” For example:

“Then it seemed good to the Apostles and the elders, with the whole church, to choose men from among them and send them to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas” (Acts 15:22).

The opening of the letter was also clear as to who was its author:

“The brethren, both the Apostles and the elders, to the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch and Syria and Cilicia, greeting” (Acts 15:23).

Acts 16 describes the letter as containing “the decisions which had been reached by the Apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem” (Acts 16:4).

So what do I mean by “Apostolic”? Merely that Apostles attended and participated in the decision-making? No, that’s simple and obvious for everyone to see. Rather, this realization had to do with a crucial detail that many often miss, namely: the exercise of apostolic authority by non-Apostles.

First, let’s be clear what “apostolic” means, in its most basic sense: that authority that Jesus granted to His Apostles, or “sent ones,” namely the authority to teach, to baptize, to forgive sins, and to govern His people. And since such authority came from Jesus, who is God, apostolic authority is inherently divine authority. It is one of the visible means by which God exercises authority in the world.

Now, if apostolic authority was granted by God to men, then when exercised by men, it is divine authority. Additionally, if the Council of Jerusalem, a group of men, were claiming to have divine authority, then they were necessarily claiming to have apostolic authority as well, as no other authority can be divinely binding on all Christians.

But, not all the men taking part in the Council that was claiming apostolic authority were Apostles. The Council of Jerusalem exhibited the reality of non-Apostles (those not among the twelve, or the few others that came afterward, such as Matthias and Paul) exercising divine authority. I realized it was logically impossible to avoid this conclusion. The syllogism goes something like this:

Major Premise: The Council claimed divine authority

Minor Premise: The Apostles and the elders were those who exercised the Council’s authority

Conclusion: The Apostles and the elders were exercising divine authority

What was going on here? How could non-Apostles, but those appointed by Apostles, be exercising divine authority? Didn’t Jesus only give that to the Apostles?

And then I remembered my Euclid, whose first “General Axiom” was as follows: “Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to one another.” In other words, if A = C, and B = C, then it is absolutely certain that A = B. Both A and B, by claiming to be equal to C, are in fact equal to each other as well.

Then it hit me: at the Council of Jerusalem, Apostles claimed divine authority. At the Council of Jerusalem, non-Apostles also claimed divine authority. Therefore, the non-Apostles at the Council of Jerusalem were, by virtue of the claim that they were partaking in an act that had divine authority, also claiming to have, in one form or another, apostolic authority. As the Apostles had been “sent” by Jesus, so they had been “sent” by the Apostles.

This didn’t make the elders equal in every way with the Apostles (as we will see under my fifth realization about the hierarchical nature of the Council). But it meant that in some fundamental way, their exercise of authority was the same. The elders were, in fact, exercising divine authority along with the Apostles.

After all, this divinely-vouched and binding decision was rendered not just by Apostles, but also by those whom the Apostles had appointed in positions of authority. These were the “elders,” which included those from Jerusalem, as well as others who were appointed by local churches abroad, such as Barnabas, who attended the Council with Paul. They, themselves, were part of this apostolic decision, which means that apostolic succession—the succession of bishops from the Apostles as the governors of the Church—was already beginning from the earliest days of the Church. Indeed, it had begun before the vast majority, perhaps any of the New Testament had even been written. Not only that, but such men were part of a decision that claimed to have divine authority.

And in the Church, the only authority that can claim to be divine is apostolic authority. And that’s precisely what we see at the Council of Jerusalem—apostolic authority exercised by both Apostles (the twelve + Matthias and Paul) and those they had appointed (the elders).

Apostolic Succession was already being exercised, and taken for granted in the early Church (the details of which I’ll leave for other posts).

This absolutely puzzled me as a protestant. Where was that Church today? I asked. Are we just out of luck that we didn’t solve all the theological issues in the first century? How could mere men have divine authority?

But, as I would later go on to discover, this makes perfect sense in light of Jesus’ words about the ongoing guidance of the Church until His return, both by Him, and the Holy Spirit (see, for example, Matthew 28:18-20; John 14:26; John 16:7, 12-15, etc.). Fleshing out that immense topic is for another day.

In short, I realized that the Catholic Church had been right again, and it had been right there, staring me in the face. No wonder I could never square any of this with my native protestantism. It simply makes no sense in that framework.

This led me to my final realization.

(5) HIERARCHICAL

The Council’s decision was exercised in accordance with a hierarchical structure of Church government. All of those making the decisions of the Council were exercising apostolic authority, but not in the same degree. It was exercised by (in ascending authority) the elders, the Apostles, and the Chief Apostle, Peter.

In short, we see precisely what we would expect to see if the Catholic Church’s claims about the hierarchical nature of the Church are true. Specifically, the Church claims to be governed by the successors of the very men we see at the Council of Jerusalem: a Church governed at the lowest level by priests (elders), who are governed by the successors of the Apostles (the Bishops), in union with the successor of Peter (the Pope).

Peter (the Pope) governs universally, and the Apostles (the Bishops) govern locally, supervising the elders (priests) in their respective territories. This basic structure was also part of the Jewish polity, which had its High Priest, its chief priests, and its elders (see, for example, Matt. 26:3).

The word for “elder” in this place is presbyteros (the word that would eventually become “priest” in English). It is the same word used for the Jewish authorities in places like Matthew 26:3, those who made up the Sanhedrin, the governing body of the Jewish people (many of whom were priests). It is also the same word used in Acts 20:17 for the “elders” of the Ephesian church, who Paul said ruled over “the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you guardians…” (i.e. again, they ruled by divine authority bestowed on them by the Apostles). While the word could be, and was used to refer to older people in general, it was used over and over again throughout Scripture to refer to the governing authorities of both the Jewish people, and then the Church.

Peter’s Papal Authority

Some may be willing to concede that they see the Apostles as the first Bishops, and the elders as the first priests. But was Peter really exercising his authority as Pope? This claim, while believed by Catholics worldwide, is nonetheless rejected by most non-Catholic Christians.

So I’d like to present some evidence that Peter was, in fact, exercising papal authority at the Council of Jerusalem. We see him exercise this authority in three main ways.

First, Peter claims that it was by “my mouth” that God decided to proclaim the Gospel to the nations, or “Gentiles” (Acts 15:7). By so claiming, especially at a Council that was seeking to determine which parts of the Mosaic law would apply to Gentiles, Peter is claiming to have the ultimate say in the matter.

That Peter’s successors have always seen themselves in the same way throughout history is eminently provable. But it is an enormous topic that goes beyond the purpose of this particular blog. However, one could simply point to one example (among many), not even from a Pope, but from the Council of Chalcedon, widely acknowledged even by protestants to have been an ecumenical Council of the Church, when it wrote to Pope St. Leo the Great as follows:

”[G]o ye and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them into the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, teaching them to observe all things that I have enjoined you” (Matt. 28:19-20). And this golden chain leading down from the Author of the command to us, you yourself have steadfastly preserved, being set as the mouthpiece unto all of the blessed Peter, and imparting the blessedness of his Faith unto all. [Emphasis added]

The Council of Chalcedon thus uses language about one of Peter’s successors that precisely mirrors the language used by Peter himself—that of a “mouthpiece,” or “mouth” for the propagation and instructing in the Faith. Referring to the Pope in this way was quite common in the ancient Church, particularly after the Council of Nicaea.

Second, Peter exercises his authority in a way that fulfills the type of King David at the Old Testament “Council of Jerusalem.” Many people have no idea what I’m talking about, but this is, for me, one of the most stunning proofs of the Catholic concept of the papacy.

At the end of the Council, James cites from the book of Amos. I’ve already quoted that verse several times. The relevant portion of it speaks of raising up “the booth of David that is fallen…” (Amos 9:11). But what is “the booth of David”? A “booth” was a tabernacle. The Mosaic Feast of Tabernacles is sometimes known as the Feast of Booths, and took place when the people of Israel built their own mini-tabernacles (in imitation of the great mobile Tabernacle that traveled with them through the desert). The Tabernacle was, of course, an early version of the Temple that would eventually be built in Jerusalem, and that is the “booth” being referred to here. How do we know? Because David was the one who purchased the threshing floor on top of Mount Moriah upon which to build that Temple (see 2 Sam. 24). This was because when God made a covenant with David, He specifically ordered Him to “build me a house to dwell in” (see 2 Sam. 7), despite the fact that actually building it was left to Solomon (who followed plans provided by David).

So why is James citing this verse about the old Temple in relation to the Council of Jerusalem? Because the Council was essentially focused on what was necessary to becoming a part of the New People of God, composed of both Jew and Gentile, who worshiped in the New Temple, the Church.

The Old Testament Council of Jerusalem

So James refers back to an Old Testament prophecy about the first Temple, the type of the Church, whose building was assigned to David, the type of the Messiah. That prophecy says that the Temple will be rebuilt, and that when it is, the nations of the earth will flood into it. He is doing this at the first Council of the Church, and the issue at hand is “how does one get admitted into this New Temple, the Church?” The New Temple is being “built,” and James assumes that this is directly related to Amos’ prophecy concerning David’s Temple.

So since we know David was a type of Christ, and the Jewish Temple was a type of the Church, is there a type related to the building of the first Temple that corresponds with its fulfillment at the Council of Jerusalem, which James understands as a “rebuilding” of that Temple in a new and more glorious fashion?

As it turns out, there is. It is found in 1 Chronicles 28. Like the Council of Jerusalem, this first “Council of Jerusalem” also concerned the Temple of God, the “booth of David” referred to by Amos. This is where it gets particularly interesting with respect to the papacy.

David, as the earthly head of the People of God (the Israelites) presided over the first “Council of Jerusalem.” Likewise, Peter, the earthly head of the People of God (the Church, consisting of both Jews and Gentiles), presided over the New Testament Council of Jerusalem. There is an extraordinary congruity between the words of David, and the words of Peter at their respective councils. Read typologically (the way Jesus and the Apostles interpreted the Scriptures), this would mean that since David was the head of the People of God on earth, then Peter must be the New Head of the New People of God on earth, namely, the Church.

One needs only examine the language of each at their respective councils. David, after convening all the leaders of Israel for the council, addresses them as follows (1 Chron. 28:2, 4, 8):

“Hear me, my brethren and my people…Yet the Lord God of Israel chose me from all my father’s house to be king over Israel forever…Now therefore in the sight of all Israel, the assembly of the Lord, and in the hearing of our God, observe and seek out all the commandments of the Lord your God; that you may possess this good land, and leave it for an inheritance to your children after you forever.”

Peter’s words are remarkably similar (Acts 15:7, 10):

“Brethren, you know that in the early days God made choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe…Now therefore why do you make trial of God by putting a yoke upon the neck of the disciples which neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? But we believe that we shall be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will.”

When analyzed in a parallel fashion, the similarities are striking.

| DAVID (1 Chron. 28) | ST. PETER (Acts 15) |

| Hear me, my brethren and my people… | Brethren… |

| Yet the Lord God of Israel chose me from all my father’s house… | you know that in the early days God made choice among you… |

| to be king over Israel forever… | that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe. |

| Now therefore… | Now therefore… |

| in the sight of all Israel, the assembly of the Lord… | why do you… |

| and in the hearing of our God… | make trial of God… |

| observe and seek out all the commandments of the Lord your God… | by putting a yoke upon the neck of the disciples which neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? |

| that you may possess this good land, and leave it for an inheritance to your children after you forever. | But we believe that we shall be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will. |

Both David and Peter follow a speech pattern that corresponds to each other, not only in content, but even in the very order they appear.

First, each calls the attention of the full council, and addresses the attendees as “brethren.”

Second, each identifies themselves as the object of God’s choice from among His followers.

Third, each identifies the essential function for which they were appointed: David to be King of Israel, and Peter to be the mouth by which the Gospel would be taught to all “the Gentiles,” which simply meant “the nations.” This could only mean that Peter was the head of the Church by which that would be accomplished.

Fourth, they each make clear that this calling entitles them to make a certain judgment, hence the use of “Now therefore…” by both.

Fifth, they preface their decision by appealing to the leaders as a whole—David to those of Israel, and Peter to the Apostles and elders.

Sixth, both appeal to the witness of God for the issue at hand—and this is the point at which the nature of the Old Covenant and the New Covenant are made clear.

Seventh, they both speak to their view of the status of the Mosaic laws—David calling for obedience to them, and Peter pointing out that the law of Moses, on its own, saves no one (just as the promulgation of any law doesn’t mean it will be obeyed).

Finally, both conclude with their understanding of the ultimate purpose of obeying God—David in obeying the Mosaic law to continue to inhabit the Land of Israel, and Peter in the grace of God (participation in the Divine Life of the Trinity) which allows one to live in Heaven for eternity. Thus, both conclude by summarizing the basic understanding of their respective covenants.

This cannot possibly be a coincidence. As such, since David was the earthly head of the people of Israel, Peter is the earthly head of the Church. This is perhaps one of the most overlooked proofs of the Catholic notion of the papacy—that the head of Christ’s Church on earth, his “prime minister” of sorts, is none other than Peter and his successors, just as the head of ancient Israel was David and his successors, who were the beneficiaries of the Davidic Covenant that most clearly foreshadowed a coming Messianic King. The Davidic monarchy didn’t die with David, nor did the primacy of Peter die with Peter. Both David and Peter held offices, and those offices continued to exist after they themselves died, and were filled by their successors—David by the kings of Israel (then Judah), and Peter by the Popes. There is perhaps no clearer confirmation of this then the fact that David entrusted the actual building of the Temple to his successor, King Solomon, who was to follow the plan provided to him by his father. In the same way, the Popes have continued to build the New Temple, the Catholic Church, throughout the world for the last 2,000 years. And, like the kings of Israel, and then Judah, some of them have been righteous, holy men, and others have been scoundrels. But all of them held an office established by God in both cases.

Peter’s Voice Was the Decisive One

Third, and finally, Peter issued the permanently binding part of the decision of the Council, namely, that the Gentiles would not be bound to be circumcised to become part of the Church. One became a Christian through baptism, not circumcision. Christians who had been baptized were not, as some had told them, required to be circumcised to be saved, for circumcision was merely an outward physical sign, whereas baptism wrought a spiritual reality in the soul, a true cleansing from sin, just as was prophesied by the prophet Jeremiah (see Jer. 31:31-34).

After Peter made this clear, “all the assembly kept silence” (Acts 15:12), and there was not a single word that contradicted him afterward. Indeed, only support is offered for what Peter said, first by Barnabas, then Paul, and finally by James, who uses Peter’s words on the permanent teaching of the Church to arrive at a judgment on the non-permanent, or disciplinary measures of the Council (namely, the part about abstaining from food offered to idols, etc.).

This is important to recognize, as some argue that James’ declaration of “my judgment is” (Acts 15:19) meant he was the head of the Council. But how could that be so? James himself refers back to Peter’s words when he declares, prior to reaching his conclusion, “Symeon has related how God first visited the Gentiles, to take out of them a people for his name. And with this the words of the prophets agree…” (Acts 15:14-15). He then cites Amos, and follows it with a “Therefore…” Thus, James not only begins his own argument with Peter’s words, but never challenges them, nor presumes to arrive at the same judgment, but rather comes to a judgment about the non-permanent rulings of the Council based on the “ground truth” of Peter’s doctrinal declaration.

James is also not found in the Old Testament type of the same Council as clearly and strikingly as is Peter.

Finally, James only speaks to the disciplinary measures of that time—most of which have been irrelevant to Christianity for the last 2,000 years. When was the last time Christians were told to abstain from certain foods because they were offered to idols, or because the animals had been strangled (which James recommends)? On the other hand, Peter’s articulation of the faith—that Christians need not be circumcised to be Christians—has remained a permanent feature of the Christian faith for 2,000 years, and was in fact the primary issue at the Council of Jerusalem.

Confirmation from the Patristic Era

This isn’t just my interpretation. Multiple figures from the patristic era, both east and west, concur in interpreting Peter as the leader of the Council of Jerusalem. I’ll cite three: St. Jerome (from the west), Theodoret of Cyrus (a bishop from the east), and Theodore Abū Qurrah (a bishop from the east).

St. Jerome explicitly addresses Peter’s role at the Council of Jerusalem in a letter to St. Augustine:

(§7) …And when there had been much disputing, Peter rose up, with his wonted readiness, and said, “Men and brethren…But we believe that, through the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, we shall be saved, even as they. Then all the multitude kept silence”; and to his opinion the Apostle James, and all the elders together, gave consent.

(§8) These quotations should not be tedious to the reader, but useful both to him and to me, as proving that, even before the Apostle Paul, Peter had come to know that the law was not to be in force after the gospel was given; nay more, that Peter was the prime mover in issuing the decree by which this was affirmed. Moreover, Peter was of so great authority, that Paul has recorded in his epistle: “Then, after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to see Peter, and abode with him fifteen days” (Gal. 1:18). In the following context, again, he adds: “Then, fourteen years after, I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas, and took Titus with me also. And I went up by revelation, and communicated unto them that gospel which I preach among the Gentiles”; proving that he had not had confidence in his preaching of the gospel if he had not been confirmed by the consent of Peter and those who were with him…No one can doubt, therefore, that the Apostle Peter was himself the author of that rule with deviation from which he is charged. The cause of that deviation, moreover, is seen to be fear of the Jews. For the Scripture says, that “at first he did eat with the Gentiles, but that when certain had come from James he withdrew, and separated himself, fearing them which were of the circumcision.”…

Likewise, an eastern bishop considered a saint in some eastern apostolic churches, Theodoret of Cyrus, in a letter to St. Pope Leo the Great, says that it was St. Peter who rendered the final verdict on this early question in the Church:

(§1) If Paul, the herald of the Truth, the trumpet of the Holy Ghost, had recourse to the great Peter in order to obtain a decision from him for those at Antioch who were disputing about living by the Law, much more do we small and humble folk run to the Apostolic See to get healing from you for the sores of the churches. For it is fitting that you should in all things have the pre-eminence, seeing that your See possesses many peculiar privileges.

For other cities get a name for size or beauty or population, and some that are devoid of these advantages are compensated by certain spiritual gifts: but your city has the fullest abundance of good things from the Giver of all good. For she is of all cities the greatest and most famous, the mistress of the world and teeming with population. And besides this she has created an empire which is still predominant and has imposed her own name upon her subjects. But her chief decoration is her Faith, to which the Divine Apostle is a sure witness when he exclaims “your faith is proclaimed in all the world” (Rom. 1:8); and if immediately after receiving the seeds of the saving Gospel she bore such a weight of wondrous fruit, what words are sufficient to express the piety which is now found in her?

She [Rome] has, too, the tombs of our common fathers and teachers of the Truth, Peter and Paul, to illumine the souls of the faithful. And this blessed and divine pair arose indeed in the East, and shed its rays in all directions, but voluntarily underwent the sunset of life in the West, from whence now it illumines the whole world. These have rendered your See so glorious: this is the chief of all your goods. And their See is still blessed by the light of their God’s presence, seeing that therein He has placed your Holiness to shed aboard the rays of the one true Faith.

St. Pope Leo the Great quite explicitly affirmed Theodoret’s assertions about the papacy, and his authority as Peter’s successor.

Finally, we’ll cite a lesser-known eastern bishop from the 9th century, Theodore Abū Qurrah, who very explicitly affirmed in his work, On the Councils, that Peter was not only the leader of the Council of Jerusalem, but was the leader of all successive ecumenical councils in the person of the Pope, his successor.1

Referring to the Judaizing controversy and its resolution at the Council of Jerusalem, Qurrah wrote as follows (pg. 67):

When the two groups quarreled in Antioch about the subject of their disagreement, the church accepted the opinion of neither Paul and Barnabas nor of those other men. Rather, they referred all of them to the council of apostles, of which St. Peter was the head and leader.

Such is the witness of the patristic era about the Council of Jerusalem.

Conclusion: Where is that Church today?

With that, I bring this much longer post to a close. I thank you if you have stayed with me this long. But I felt it was worth thoroughly unpacking, for it is indeed difficult to overestimate the importance of Acts 15 to my journey toward the Catholic Church. Long before I had ever read a single word by a Catholic apologist or a Church Father, I read the Bible’s account of the Council of Jerusalem and simply had no way to fit it into any of a variety of protestant frameworks for a “biblical church.” Further study eventually led me to conclude that the Church, from its earliest days, was (1) Catholic; (2) Authoritative; (3) Infallible; (4) Apostolic; and (5) Hierarchical in a way that matched the Catholic Church to this very day.

I was thus faced with a fundamental question—since the Bible clearly portrays a Church of this nature, and never claims that such a Church came—or would come—to an end, where is that Church today?

I suspect my conclusion is obvious.

Footnotes

- Theodore Abū Qurrah, John C. Lamoreaux, trans., Theodore Abū Qurrah (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 61-81. ↩︎