Relevant Resources

- Quote Archive | The Sacrament of Confession

Introduction

This story is from my adolescence, when I read a verse in the Gospel of John that shocked me to my core. I had read the whole Gospel before, but for whatever reason, this verse fell on me like a pile of bricks. In short, it simply made no sense within the broad protestant, evangelical framework I and many of those around me possessed. I did not perceive it at the time, but in hindsight, this incident certainly played a role in my eventual conversion to the Catholic Faith. Serious questions about this verse of Scripture led to many more, which eventually led to the unraveling of many of my protestant ideas–much of which occurred before I had read any Catholics, or the Church Fathers.

Roadmap

Our Roadmap is as follows:

- I will tell the story about my reading John 20:21-23, and why it was so shocking;

- I will explain why some of the commentaries I had from respected protestant sources provided unsatisfying explanations of this verse; and

- I will tell the story of how my hoped-for resolution to the problem didn’t materialize, leaving me with a huge question about not only the meaning of this verse, but my understanding of the Gospel itself; and finally

- I will share two quotes from Church Fathers (just the tip of the iceberg) who I did not even know existed at the time, but which indicate the profoundly Catholic consensus of the ancient Church on these verses that scandalized me so much as a protestant.

A Disturbing Verse

Since I was a boy, I loved the Bible. I read and discussed it all the time with my parents, friends, and mentors. My parents helped me get multiple study Bibles over the years.

But I remember clear as day being a teenager, and reading this verse for what felt like the first time. I was completely baffled (John 20:21-23):

Jesus said to them [the Apostles] again, “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, even so I send you.” And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

I read this verse, and understood it to clearly say that Jesus gave the Apostles the authority to forgive or not forgive sins. But this made no sense in my protestant, evangelical framework.

In our theology, when we became Christians, all our past, present, and future sins were forgiven at that one moment. Men had no role to play in extending or retracting this forgiveness from us.

“Only God can forgive sins,” I thought to myself. If the Apostles could forgive sins, that seemed to imply the Gospel I had learned was false. Even protestants I knew who believed you could lose your salvation believed all we had to do to be forgiven was pray to God. Men simply weren’t involved, and the idea that they would be was grotesque.

But this verse clearly said something very different. If the Apostles could forgive sins, that meant the Gospel the earliest Christians learned was quite different than the one I knew, a reality that for one reason or another hit me for the first time when I read this verse as a teenager.

A Disturbing Lack of Answers

So I went to the study Bibles. We had at least three at the time. The ones I remember were the Geneva Study Bible, the Reformation Study Bible, and the ESV Study Bible.

I went straight to that verse in one of them (I forget which one), eager for an answer. The commentary was blank. The verses were simply skipped.

Then I went to the other two, whose commentary amounted to saying “the verse doesn’t mean what it plainly says.” I remember being very disappointed by these “explanations.”

Here is an example from the ESV Study Bible:

The expressions “they are forgiven” and “it is withheld” both represent perfect-tense verbs in Greek and could also be translated, “they have been forgiven” and “it has been withheld,” since the perfect gives the sense of completed past action with continuing results in the present. The idea is not that individual Christians or churches have authority on their own to forgive or not forgive people, but rather that as the church proclaims the gospel message of forgiveness of sins in the power of the Holy Spirit (see v. 22), it proclaims that those who believe in Jesus have their sins forgiven, and that those who do not believe in him do not have their sins forgiven–which simply reflects what God in heaven has already done.

This explanation was untenable to me then, as it is untenable to me now. The reason is very simple: it fails to address the persons Jesus is ascribing this authority to, as well as the contingent nature of its operation. Even if I substituted their alternative translation into the verse, it would still result in this the following, with their alternative translation in brackets (John 20:23, ESV):

If you forgive the sins of any, [they have been forgiven]; if you withhold forgiveness from any, [it has been withheld].

This version of the verse seemed virtually identical to me. Indeed, the fact that the words apparently described a “completed action with continuing results in the present” seemed pretty straightforward in this case: the “completed action” was Christ’s sacrifice, which was sufficient for the forgiveness of all sins; and the “continuing results” was the application of that action to particular people.

But that didn’t deal with the key issue the verse presented me with: the ascription of this authority to the Apostles. The red flags for me were “If you forgive the sins of any,” and “if you withhold forgiveness from any.” Of what man or men, even a group as august as the Apostles, could we ever speak this way? In our theology, no one. Only God. And yet here was Jesus, clearly ascribing it to men. The fact that those men were the Apostles didn’t change the shock of it. If our theology was correct, it was scandalous that any man would have such authority.

Indeed, the use of this authority was preceded by a contingent “If,” which the Strong’s Concordance I had at the time (a standard reference work for the meaning of words in the Bible) defined as (Strong G302):

A particle indicating that something can or could occur on certain conditions, or by the combination of certain fortuitous causes.

The weight of this contingent “if” was put on “you,” the Apostles, as was the action of forgiving or not. That was the crux of the problem, and the perfect tense of the following verbs didn’t change that.

So the basic problem I had with the verse remained. Authority was being ascribed to the Apostles that I simply had no room for in my theology, or the theology of my various protestant study Bibles. For a Christian whose entirely theology was based on the Bible (or so I believed), this was a shock to my system that needed to be remedied.

A Disappointing Silence

At the time, I was teaching piano lessons on the side to earn some spending money. I saved up approximately $60 so I could buy another study Bible to hopefully find better answers. I believe it was the MacArthur Study Bible (an earlier version), a study Bible published by the well-known and respected evangelical pastor, John Macarthur. He was well known for teaching Scripture verse by verse, and was respect by both myself, and many people around me. If anyone knew what this verse meant, I thought, it would be John Macarthur.

When it arrived, I was giddy with excitement, convinced I would finally get an answer. I ripped open the box, opened the Bible to John 20, and–nothing. The verses were completely skipped. I was crushed.

At the time, I wasn’t “anti-Catholic,” but I had a general sense of “we left those quasi-pagans for good reasons, and good riddance.” I loved Martin Luther, but only because I had been taught to do so. I had never seriously questioned whether he and the other protestant “reformers” were worthy of such love. While I was very confused about this verse, I assumed some great theologian or teacher had figured it out. As time went on, I occasionally read more commentaries on this verse. Time and again, they rarely made much sense. All of them basically denied the verse stated what it plainly stated, usually along the lines of what the MacArthur Study Bible (current edition) in my library today states1:

This verse does not give authority to Christians to forgive sins. Jesus was saying that the believer can boldly declare the certainty of a sinner’s forgiveness by the Father because of the work of his Son if that sinner has repented and believed the gospel. The believer with certainty can also tell those who do not respond to the message of God’s forgiveness through faith in Christ that their sins, as a result, are not forgiven.

Clearly the verse says nothing like this, and I thought so at the time, both loving John MacArthur, and not having a Catholic bone in my body. Jesus isn’t speaking to all believers, but only the Apostles. Jesus didn’t say anything about certainty. He said the Apostles could forgive or not forgive sins. They were the agents He referred to. Jesus had other followers at the time, but didn’t say this to them. Even if it did include all believers, the verse still made no sense to be because it ascribed the authority to forgive or not forgive sins to men.

I remember how much doubt this verse gave me as a teenager. I trusted someone had figured it out. Nonetheless, I was genuinely shocked by it, and the answers I was given were completely unconvincing. It was the first of many such experiences of reading the Bible and thinking “how on earth does this make sense in our theological framework?”

While I did not perceive it at the time, this verse had in fact begun my long journey toward the Catholic Church. Its plain meaning was so jarring, so contrary to everything I believed, and so inadequately explained, that all I had to fall back on was a belief that someone else, a yet to be discovered theologian or preacher, had figured it out and threaded the needle for me.

Short version of that story: I never found them.

However, after discovering the Church Fathers, this verse is no longer confusing. They routinely interpreted it to refer to the Sacrament of Confession, which is now a regular part of my life as a Catholic (see Quote Archive | The Sacrament of Confession).

The Tip of the Patristic Iceberg

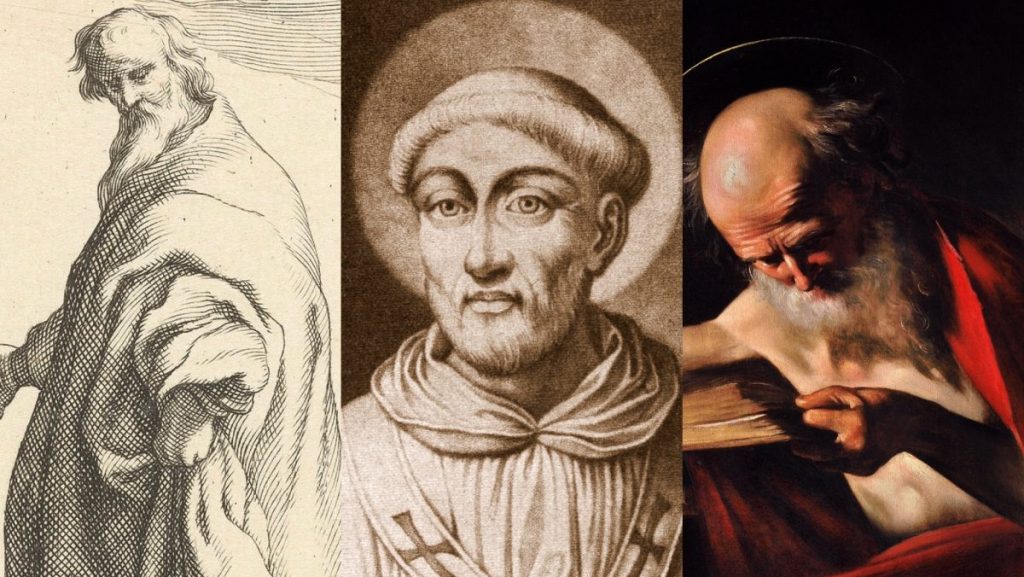

Here are two quick examples from the writings of the Church Fathers to show evidence of this.

First, in Concerning Repentance, St. Ambrose, a 4th century western Church Father who received St. Augustine into the Catholic Church, wrote as follows on this verse (Book 1, Ch. 2, §7):

Rightly, therefore, does the Church claim it [the authority to forgive/retain sins], which has true priests; heresy, which has not the priests of God, cannot claim it. And by not claiming this power heresy pronounces its own sentence, that not possessing priests it cannot claim priestly power. And so in their shameless obstinacy a shamefaced acknowledgment meets our view.

Second, in his Treatise Concerning the Christian Priesthood, St. John Chrysostom, a 4th century eastern Church Father wrote as follows (Book 3, §5):

For if any one will consider how great a thing it is for one, being a man, and compassed with flesh and blood, to be enabled to draw near to that blessed and pure nature [i.e. God], he will then clearly see what great honor the grace of the Spirit has vouchsafed to priests; since by their agency these rites [the sacraments] are celebrated, and others nowise inferior to these both in respect of our dignity and our salvation.

For they who inhabit the earth and make their abode there are entrusted with the administration of things which are in Heaven, and have received an authority which God has not given to angels or archangels. For it has not been said to them, “Whatsoever you shall bind on earth shall be bound in Heaven, and whatsoever you shall loose on earth shall be loosed in Heaven” (Matt. 18:18). They who rule on earth have indeed authority to bind, but only the body; whereas this binding lays hold of the soul and penetrates the heavens; and what priests do here below God ratifies above, and the Master confirms the sentence of his servants. For indeed what is it but all manner of heavenly authority which He has given them when He says, “Whose sins you remit they are remitted, and whose sins you retain they are retained”(John 20:23)? What authority could be greater than this? “The Father has committed all judgment to the Son” (John 5:22). But I see it all put into the hands of these men by the Son. For they have been conducted to this dignity as if they were already translated to Heaven, and had transcended human nature, and were released from the passions to which we are liable.

These two quotes, representing both the western and eastern halves of the ancient Christian world, are just the tip of the iceberg. At the time when I was shocked by these words of Christ as a teenager, I did not even know these men existed, or that they had written such things. But once I became familiar with them and many more like them in the ancient Church, the protestant clouds of scandal and confusion evaporated before the sun of Catholic clarity and coherence.

Praise be to God!

Footnotes

- John MacArthur, ed., The MacArthur Study Bible, 2nd ed. (Thomas Nelson, 2021), 1481. ↩︎