(Updated May 28, 2025)

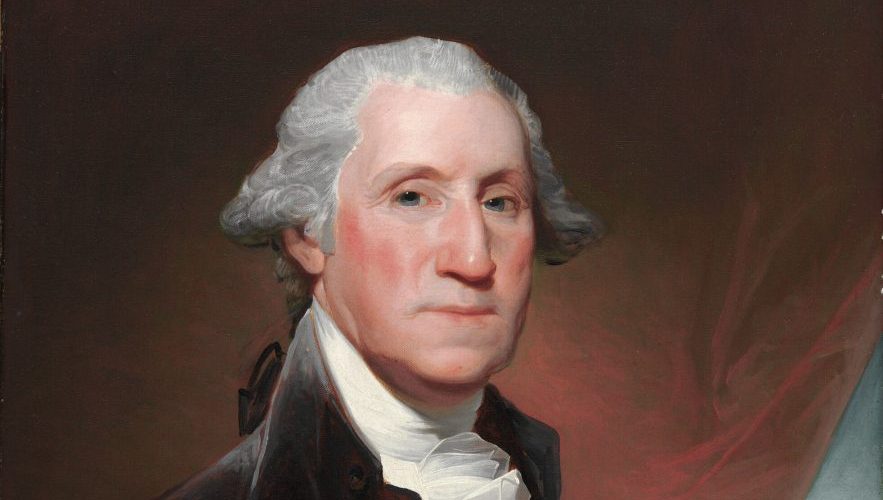

George Washington (1732-1799) was an American Founder who is considered the “Father of His Country.” He served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and as the United States’ first President.

Next to each quote are the Topic Quote Archives in which they are included.

This Quote Archive is being continuously updated as research continues. Quotes marked with “***” have not yet been organized into their respective Topic Quote Archives.

General and Other Military Orders

George Washington, Address to the Continental Congress (June 16, 1775)

The President informed Colonel Washington that the Congress had yesterday unanimously made choice of him to be General and Commander in Chief of the American forces…

[W]hereupon Colonel Washington, standing in his place, spoke as follows: “Though I am truly sensible of the high honor done me in this appointment, yet I feel great distress from a consciousness that my abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust…I will enter upon the momentous duty and exert every power I possess in their service and for the support of the glorious…

I this day declare with the utmost sincerity I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with. As to pay sir, I beg leave to assure the Congress that as no pecuniary [financial] consideration could have tempted me to have accepted this arduous employment at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it: I will keep an exact account of my expenses; those I doubt not they will discharge and that is all I desire.”

George Washington, Address to the New York Provincial Congress (June 26, 1775)

I deplore the unhappy necessity of such an appointment [Washington’s] as that with which I am now honored, I cannot but feel sentiments of the highest gratitude for this affecting instance of distinction and regard…

[A]nd be assured that every exertion of my worthy colleagues and myself will be equally extended to the re-establishment of peace and harmony between the Mother Country [Great Britain] and the colonies.

When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen, and we shall most sincerely rejoice with you in that happy hour when the establishment of American liberty on the most firm and solid foundations shall enable us to return to our private stations in the bosom of a free, peaceful, and happy country.

George Washington, General Orders (July 4, 1775)

The Continental Congress having now taken all the troops of the several Colonies which have been raised, or which may be hereafter raised for the support and defense of the liberties of America into their pay and service. They are now the troops of the United Provinces of North America, and it is hoped that all distinctions of colonies will be laid aside so that one and the same spirit may animate the whole, and the only contest be who shall render on this great and trying occasion the most essential service to the great and common cause in which we are all engaged.

The General most earnestly requires, and expects, a due observance of those articles of war, established for the Government of the army, which forbid profane cursing, swearing and drunkenness; And in like manner requires and expects, of all Officers, and Soldiers, not engaged on actual duty, a punctual attendance on divine service, to implore the blessings of heaven upon the means used for our safety and defense.

All officers are required and expected to pay diligent attention to keep their men neat and clean—to visit them often at their quarters, and inculcate upon them the necessity of cleanliness as essential to their health and service.

Colonel Gardner is to be buried tomorrow at 3 o’clock PM with the military honors due to so brave and gallant an officer, who fought, bled, and died in the Cause of his country and mankind.

George Washington, General Orders (July 16, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Continental Congress having earnestly recommended, that “Thursday next the 20th Instant, be observed by the Inhabitants of all the English Colonies upon this Continent; as a Day of public Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer; that they may with united Hearts and Voice, unfeignedly confess their Sins before God, and supplicate the all wise and merciful disposer of events, to avert the Desolation and Calamities of an unnatural war”: The General orders, that Day to be religiously observed by the Forces under his Command, exactly in manner directed by the proclamation of the Continental Congress: It is therefore strictly enjoined on all Officers and Soldiers (not upon duty), to attend Divine Service, at the accustomed places of worship, as well in the Lines, as the Encampments and Quarters; and it is expected, that all those who go to worship, do take their Arms, Ammunition and Accoutrements, and are prepared for immediate Action if called upon. If in the Judgment of the Officers, the Works should appear to be in such forwardness as the utmost security of the Camp requires, they will command their men to abstain from all Labor upon that solemn day.

George Washington, To the Inhabitants of Bermuda (September 6, 1775)

As the descendants of free men and heirs with us of the same glorious inheritance, we flatter ourselves that though divided by our situation, we are firmly united in sentiment. The cause of virtue and liberty is confined to no continent or climate it comprehends within its capacious limits the wise and the good however dispersed and separated in space or distance. You need not be informed that the violence and rapacity of a tyrannical Ministry [the British government] have forced the citizens of American, your brother colonists, into arms.

The wise Disposer of all events have hitherto smiled upon our virtuous efforts…The virtue and spirit and union of the provinces leave them nothing to fear but the want of ammunition.

We are informed that there is a large magazine in your island under a very feeble guard. We would not wish to involve you in an opposition in which your situation we should be unable to support you, we know not therefore to what extent to solicit your assistance in availing ourselves of this supply. But if your favor and friendship to North America and its liberties have not been misrepresented, I persuade myself you may, consistent with your own safety, promote and favor this scheme so as to give it the fairest prospect of success.

George Washington, To the Inhabitants of Canada (September 14, 1775)

The unnatural contest between the English colonies and Great Britain has now risen to such a height that arms alone must decide it. The colonies, confiding in the justice of their cause, and the purity of their intentions, have reluctantly appealed to that Being in whose hands are all human events. He has hitherto smiled upon their virtuous efforts—the hand of tyranny has been arrested in its ravages, and the British arms which have shone with so much splendor in every part of the globe are now tarnished with disgrace and disappointment…While the trueborn Sons of America, animated by the genuine principles of Liberty and love of their country, with increasing Union, firmness, and discipline, repel every attack, and despise every danger.

They [the British] have persuaded themselves, they have even dared to say, that the Canadians are were not capable of distinguishing between the blessings of Liberty, and the wretchedness of slavery…By such artifices they hoped to bend you to their views, but they have been deceived, instead of finding in you that poverty of soul and baseness of spirit, they see with a chagrin equal to our joy, that you are enlightened, generous, and virtuous—that you will not renounce your own rights, or serve as instruments to deprive your fellow subjects of theirs—Come then, my brethren, unite with us in an indissoluble Union, let us run together to the same goal—We have taken up arms in defense of our Liberty, our property, our wives, and our children, we are determined to preserve them, or die.

The cause of America, and of Liberty, is the cause of every virtuous American citizen. Whatever may be his religion or his descent, the United Colonies know no distinction but such as slavery, corruption, and arbitrary domination may create. Come then, ye generous citizens, range yourselves under the standard of general Liberty—against which all the force and artifice of tyranny will never be able to prevail.

George Washington, General Orders (November 5, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

As the Commander in Chief has been apprised of a design formed, for the observance of that ridiculous and childish Custom of burning the Effigy of the pope—He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers, in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are soliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship & alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defense of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered, or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.

George Washington, General Orders (November 14, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Commander in Chief is confident, the Army under his immediate direction, will shew their Gratitude to providence, for thus favoring the Cause of Freedom and America; and by their thankfulness to God, their zeal and perseverance in this righteous Cause, continue to deserve his future blessings.

George Washington, General Orders (November 18, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Honorable the Legislature of this Colony having thought fit to set apart Thursday the 23rd of November Instant, as a day of public thanksgiving “to offer up our praises, and prayers, to Almighty God, the Source and Benevolent Bestower of all good; That he would be pleased graciously to continue, to smile upon our Endeavors, to restore peace, preserve our Rights, and Privileges, to the latest posterity; prosper the American Arms, preserve and strengthen the Harmony of the United Colonies, and avert the Calamities of a civil war.” The General therefore commands, that day to be observed with all the Solemnity directed by the Legislative Proclamation, and all Officers, Soldiers and others, are hereby directed, with the most unfeigned Devotion, to obey the same.

George Washington, General Orders (November 28, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

An Express last Night from General Montgomery, brings the joyful tidings of the Surrender of the City of Montreal, to the Continental Arms—The General hopes such frequent Favors from divine providence will animate every American to continue, to exert his utmost, in the defense of the Liberties of his Country, as it would now be the basest ingratitude to the Almighty, and to their Country, to shew any the least backwardness in the public cause.

George Washington, General Orders (January 1, 1776)

His Excellency hopes that the importance of the great Cause we are engaged in will be deeply impressed upon every man’s mind, and wishes it to be considered that an army without order, regularity, and discipline, is no better than a commissioned mob. Let us therefore, when everything dear and valuable to free men is at stake, when our unnatural parent [Great Britain] is threatening of us with destruction from every quarter, endeavor by all the skill and discipline in our power to acquire that knowledge and conduct which is necessary in war—our men are brave and good, men who with pleasure it is observed are addicted to fewer vices than are commonly found in armies…

[A]t the same time, he [Washington] declares that he will punish every kind of neglect or misbehavior in an exemplary manner.

The General will, upon any vacancies that may happen, receive recommendations, and give them proper consideration, but the Congress alone are competent to the appointment.

This being the day of the commencement of the new establishment, the General pardons all the offenses of the old, and commands all prisoners (except prisoners of war) to be immediately released.

George Washington, General Orders (January 4, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

[T]hus it is that for more than two Months past I have scarcely emerged from one difficulty before I have plunged into another—how it will end God in his great goodness will direct, I am thankful for his protection to this time.

George Washington, General Orders (February 26, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

All Officers, non-commissioned Officers and Soldiers are positively forbid playing at Cards, and other Games of Chance; At this time of public distress, men may find enough to do in the service of their God, and their Country, without abandoning themselves to vice and immorality.

George Washington, General Orders (February 27, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

As the Season is now fast approaching, when every man must expect to be drawn into the Field of action, it is highly necessary that he should prepare his mind, as well as everything necessary for it. It is a noble Cause we are engaged in, it is the Cause of virtue and mankind, every temporal advantage and comfort to us, and our posterity, depends upon the Vigor of our exertions; in short, Freedom, or Slavery must be the result of our conduct, there can therefore be no greater Inducement to men to behave well: But it may not be amiss for the Troops to know, that if any Man in action shall presume to skulk, hide himself, or retreat from the enemy, without the orders of his commanding Officer; he will be instantly shot down, as an example of cowardice; Cowards having too frequently disconcerted the best formed Troops, by their dastardly behavior.

Next to the favor of divine providence, nothing is more essentially necessary to give this Army the victory of all its enemies, than Exactness of discipline, Alertness when on duty, and Cleanliness in their arms and persons; unless the Arms are kept clean, and in good firing Order, it is impossible to vanquish the enemy; and Cleanliness of the person gives health, and soldier-like appearance.

George Washington, General Orders (March 6, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

Thursday the seventh Instant, being set apart by the Honorable the Legislature of this province, as a day of fasting, prayer, and humiliation, “to implore the Lord, and Giver of all victory, to pardon our manifold sins and wickedness’s, and that it would please him to bless the Continental Arms, with his divine favor and protection”—All Officers, and Soldiers, are strictly enjoined to pay all due reverence, and attention on that day, to the sacred duties due to the Lord of hosts, for his mercies already received, and for those blessings, which our Holiness and Uprightness of life can alone encourage us to hope through his mercy to obtain.

George Washington, General Orders (May 15, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Continental Congress having ordered, Friday the 17th Instant to be observed as a day of “fasting, humiliation and prayer, humbly to supplicate the mercy of Almighty God, that it would please him to pardon all our manifold sins and transgressions, and to prosper the Arms of the United Colonies, and finally, establish the peace and freedom of America, upon a solid and lasting foundation”—The General commands all officers, and soldiers, to pay strict obedience to the Orders of the Continental Congress, and by their unfeigned, and pious observance of their religious duties, incline the Lord, and Giver of Victory, to prosper our arms.

George Washington, General Orders (June 30, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

[T]he General is persuaded from the known Zeal of the troops, that officers and men will stand in no need of arguments, to stimulate them upon common exertion upon the occasion, his anxiety for the Honor of the American Arms, and the noble cause we are engaged in…in short to be well prepared for an e[n]gagement is, under God, (whose divine Aid it behooves us to supplicate) more than one half the battle.

George Washington, General Orders (July 2, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The time is now near at hand which must probably determine, whether Americans are to be, Freemen, or Slaves; whether they are to have any property they can call their own; whether their Houses, and Farms, are to be pillaged and destroyed, and they consigned to a State of Wretchedness from which no human efforts will probably deliver them. The fate of unborn Millions will now depend, under God, on the Courage and Conduct of this army—Our cruel and unrelenting Enemy leaves us no choice but a brave resistance, or the most abject submission; this is all we can expect—We have therefore to resolve to conquer or die: Our own Country’s Honor, all call upon us for a vigorous and manly exertion, and if we now shamefully fail, we shall become infamous to the whole world—Let us therefore rely upon the goodness of the Cause, and the aid of the supreme Being, in whose hands Victory is, to animate and encourage us to great and noble Actions—The Eyes of all our Countrymen are now upon us, and we shall have their blessings, and praises, if happily we are the instruments of saving them from the Tyranny meditated against them. Let us therefore animate and encourage each other, and shew the whole world, that a Freeman contending for Liberty on his own ground is superior to any slavish mercenary on earth.

The General recommends to the officers great coolness in time of action, and to the soldiers a strict attention and obedience, with a becoming firmness and spirit.

George Washington, General Orders (July 9, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Honorable Continental Congress having been pleased to allow a Chaplain to each Regiment…The Colonels or commanding officers of each regiment are directed to procure Chaplains accordingly; persons of good Characters and exemplary lives—To see that all inferior officers and soldiers pay them a suitable respect and attend carefully upon religious exercises: The blessings and protection of Heaven are at all times necessary but especially so in times of public distress and danger—The General hopes and trusts, that every officer, and man, will endeavor so to live, and act, as becomes a Christian Soldier defending the dearest Rights and Liberties of his country.

The Honorable the Continental Congress, impelled by the dictates of duty, policy and necessity, having been pleased to dissolve the Connection which subsisted between this Country, and Great Britain, and to declare the United Colonies of North America, free and independent STATES: The several brigades are to be drawn up this evening on their respective Parades, at six o’clock, when the declaration of Congress, shewing the grounds & reasons of this measure, is to be read with an audible voice.

The General hopes this important Event will serve as a fresh incentive to every officer, and soldier, to act with Fidelity and Courage, as knowing that now the peace and safety of his Country depends (under God) solely on the success of our arms: And that he is now in the service of a State, possessed of sufficient power to reward his merit, and advance him to the highest Honors of a free Country.

George Washington, General Orders (July 21, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

[T]he General most earnestly exhorts every officer, and soldier, to pay the utmost attention to his Arms, and Health; to have the former in the best order for Action, and by Cleanliness and Care, to preserve the latter; to be exact in their discipline, obedient to their Superiors and vigilant on duty: With such preparation, and a suitable Spirit, there can be no doubt, but by the blessing of Heaven, we shall repel our cruel Invaders; preserve our Country, and gain the greatest Honor.

George Washington, General Orders (August 1, 1776)

It is with great concern, the General understands, that jealousies, etc. are arisen among the troops from the different Provinces, of reflections frequently thrown out which can only tend to irritate each other, and injure the noble cause in which we are engaged, and which we ought to support with one hand and one heart. The General most earnestly entreats the officers and soldiers to consider the consequences; that they can no way assist our cruel enemies more effectually than making divisions among ourselves; that the honor and success of the army, and the safety of our bleeding country, depends upon harmony and good agreement with each other.

That the Providences are all United to oppose the common enemy…and preserve the Liberty or our country, ought to be our only emulation, and he will be the best soldier, and the best patriot, who contributes most to this glorious work, whatever his station, or from whatever part of the Continent he may come…

George Washington, General Orders (August 3, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

That the Troops may have an opportunity of attending public worship, as well as take some rest after the great fatigue they have gone through; The General in future excuses them from fatigue duty on Sundays (except at the Shipyards, or special occasions) until further orders. The General is sorry to be informed that the foolish, and wicked practice, of profane cursing and swearing (a Vice heretofore little known in an American Army) is growing into fashion; he hopes the officers will, by example, as well as influence, endeavor to check it, and that both they, and the men will reflect, that we can have little hopes of the blessing of Heaven on our Arms, if we insult it by our impiety, and folly; added to this, it is a vice so mean and low, without any temptation, that every man of sense, and character, detests and despises it.

George Washington, General Orders (August 9, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The General exhorts every man, both officer and soldier, to be prepared for action, to have his arms in the best order, not to wander from his encampment or quarters; to remember what their Country expects of them, what a few brave men have lately done in South Carolina, against a powerful Fleet & Army; to acquit themselves like men and with the blessing of heaven on so just a Cause we cannot doubt of success.

George Washington, General Orders (August 13, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Enemy’s whole reinforcement is now arrived, so that an Attack must, and will soon be made; The General therefore again repeats his earnest request, that every officer, and soldier, will have his Arms and Ammunition in good Order; keep within their quarters and encampment, as much as possible; be ready for action at a moments call; and when called to it, remember that Liberty, Property, Life and Honor, are all at stake; that upon their Courage and Conduct, rest the hopes of their bleeding and insulted Country; that their Wives, Children and Parents, expect Safety from them only, and that we have every reason to expect Heaven will crown with Success, so just a cause. The enemy will endeavor to intimidate by shew and appearance, but remember how they have been repulsed, on various occasions, by a few brave Americans; Their Cause is bad; their men are conscious of it, and if opposed with firmness, and coolness, at their first onset, with our advantage of Works, and Knowledge of the Ground; Victory is most assuredly ours.

George Washington, General Orders (August 14, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

We must resolve to conquer, or die; with this resolution and the blessing of Heaven, Victory and Success certainly will attend us…

George Washington, General Orders (August 23, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The enemy have now landed on Long island, and the hour is fast approaching on which the honor and success of this army, and the safety of our bleeding country, depend. Remember officers and soldiers that you are free men, fighting for the blessings of liberty—that slavery will be your portion, and that of your posterity, if you do no acquit yourselves like men: Remember how your courage and spirit have been despised, and traduced by your cruel invaders, though they have found by dear experience at Boston, Charlestown, and other places, what a few brave men contending in their own land, and in the best of causes can do, against base hirelings and mercenaries.

It is the General’s express orders that if any man attempt to skulk, lay down, or retreat without Orders he be instantly shot down as an example, he hopes no such Scoundrel will be found in this army; but on the contrary, every one for himself resolving to conquer, or die, and trusting to the smiles of heaven upon so just a cause, will behave with Bravery and Resolution: Those who are distinguished for their Gallantry, and good Conduct, may depend upon being honorably noticed, and suitably rewarded: And if this Army will but emulate, and imitate their brave Countrymen, in other parts of America, he has no doubt they will, by a glorious Victory, save their Country, and acquire to themselves immortal Honor.

George Washington, General Orders (September 3, 1776) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The General hopes the justice of the great cause in which they are engaged, the necessity and importance of defending this Country, preserving its Liberties, and warding off the destruction meditated against it, will inspire every man with Firmness and Resolution, in time of action, which is now approaching—Ever remembering that upon the blessing of Heaven, and the bravery of the men, our Country only can be saved.

George Washington, To the Massachusetts General Court (November 6, 1776)

The situation of our affairs is critical and truly alarming. The dissolution of our army is fast approaching and but little, if any prospect of levying a new one in a reasonable time.

From the experience I have had of your past exertions in times of difficulty, I know that nothing in your power to effect will be wanting, and with the greatest confidence I trust that the present requisition will have your most ready approbation and compliance, being in some degree anticipated by the inquiry I have directed to be made into the state of our affairs, and whether any further aid will be necessary.

George Washington, Proclamation Concerning Loyalists (January 25, 1777)

Whereas several persons, inhabitants of the United States of America, influenced by inimical motives, intimidated by the threats of the enemy, or deluded by a Proclamation issued the 30th of November last by Lord and General Howe, styled the King’s Commissioners for granting pardons, etc. (now at open war, and invading these States) have been so lost to the interest and welfare of their country as to repair to the enemy, sign a declaration of fidelity [loyalty], and in some instances have been compelled to take oaths of allegiance to and engage not to take up arms, or encourage others so to do, against the King of Great Britain.

And whereas it has become necessary to distinguish between the friends of America and those of Great Britain, inhabitants of these States…should stand ready to defend the same against hostile invasion. I do therefore, in behalf of the United States, by virtue of the powers committed to me by Congress, hereby strictly command and require every person, having subscribed such declaration [loyalty oath to Great Britain], taken such oath, and accepted such protection and certificates from Lord and General Howe, or any person under their authority forthwith to repair to headquarters, or to the quarters of the nearest general officer of the Continental Army or Militia…and there deliver up such protections, certificates and passports, and take the oath of allegiance to the United States of America…[to loyalists] forthwith to withdraw themselves and families within the enemy’s lines, and I do hereby declare that all and every person who may neglect or refuse to comply with this order, within thirty days from the date hereof, will be deemed adherents to the King of Great Britain, and treated as common enemies of the American States.

George Washington, General Orders (February 4, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The Honorable Governor and Assembly of New-Jersey, having directed Thursday the 6th day of this Month, to be observed as a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, by the Inhabitants of the State—The General desires the same may be observed by the Army.

George Washington, General Orders (April 12, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

All the troops in Morristown, except the Guards, are to attend divine worship to morrow morning at the second Bell; the officers commanding Corps, are to take especial care, that their men appear clean, and decent, and that they are to march in proper order to the place of worship.

George Washington, General Orders (May 17, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

All the troops in, and about Morristown, (those on duty excepted) are to attend divine service, tomorrow morning.

George Washington, Circular Instructions to the Brigade Commanders (May 26, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

Let Vice and Immorality of every kind be discouraged as much as possible in your Brigade and as a Chaplain is allowed to each Regiment see that the Men regularly attend divine Worship…

George Washington, General Orders (May 31, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

It is much to be lamented, that the foolish and scandalous practice of profane Swearing is exceedingly prevalent in the American Army—Officers of every rank are bound to discourage it, first by their example, and then by punishing offenders—As a mean to abolish this, and every other species of immorality—Brigadiers are enjoined, to take effectual care, to have divine service duly performed in their respective brigades.

George Washington, General Orders (June 28, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

All Chaplains are to perform divine service tomorrow, and on every succeeding Sunday, with their respective brigades and regiments, where the situation will possibly admit of it: And the commanding officers of corps are to see that they attend; themselves, with officers of all ranks, setting the example. The Commander in Chief expects an exact compliance with this order, and that it be observed in future as an invariable rule of practice—And every neglect will be considered not only a breach of orders, but a disregard to decency, virtue and religion.

George Washington, General Orders (July 5, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

Divine service to be performed tomorrow, in all the regiments which have chaplains.

George Washington, General Orders (October 5, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

[T]hey nevertheless see that the enemy are not proof against a vigorous attack, and may be put to flight when boldly pushed—This they will remember, and assure themselves that on the next occasion, by a proper exertion of the powers which God has given them, and inspired by the cause of freedom in which they are engaged, they will be victorious.

George Washington, General Orders (October 18, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

The General has his happiness completed relative to the successes of our northern Army. On the 14th instant, General Burgoyne, and his whole Army, surrendered themselves prisoners of war—Let every face brighten, and every heart expand with grateful Joy and praise to the supreme disposer of all events, who has granted us this signal success—The Chaplains of the army are to prepare short discourses, suited to the joyful occasion to deliver to their several corps and brigades at 5 o’clock this afternoon…

George Washington, General Orders (November 30, 1777) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

[Quoting Congress] “Forasmuch as it is the indispensable duty of all men, to adore the superintending providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with gratitude their obligations to him for benefits received, and to implore such further blessings as they stand in need of: and it having pleased him, in his abundant mercy, not only to continue to us the innumerable bounties of his common providence, but also, to smile upon us in the prosecution of a just and necessary war, for the defense of our unalienable rights and liberties”—It is therefore recommended by Congress, that Thursday, the 18th day of December next be set apart for Solemn Thanksgiving and Praise, that at one time, and with one voice, the good people may express the grateful feelings of their hearts, and consecrate themselves to the service of their divine benefactor; and that, together with their sincere acknowledgements and offerings, they may join the penitent confession of their sins; and supplications for such further blessings as they stand in need of—The Chaplains will properly notice this recommendation, that the day of thanksgiving may be duly observed in the army, agreeably to the intentions of Congress.

George Washington, General Orders (December 17, 1777)

Although in some instances we unfortunately failed, yet upon the whole, Heaven hath smiled on our arms and crowned them with signal success; and we may upon the best grounds conclude that by a spirited continuance of the measures necessary for our defense, we shall finally obtain the end of our warfare, Independence, Liberty, and Peace. These are blessings worth contending for at every hazard. But we hazard nothing. The power of America alone, duly exerted, would have nothing to dread from the force of Britain. Yet we stand not wholly upon our ground.

France yields us every aid we ask, and there are reasons to believe the period is not very distance when she will take a more active part by declaring war against the British Crown. Every motive therefore irresistibly urges us, nay commands us, to a firm and manly perseverance in our opposition to our cruel oppressors, to slight difficulties, endure hardships, and contemn every danger.

…he [Washington] persuades himself that the officers and soldiers, with one heart, and one mind, will resolve to surmount every difficulty with a fortitude and patience becoming their profession, and the sacred cause in which they are engaged. He himself will share in the hardship, and partake of every inconvenience.

Day of Thanksgiving Spoken of on November 30, 1777

The Commander in Chief with the highest satisfaction expresses his thanks to the officers and soldiers for the fortitude and patience with which they have sustained the fatigues of the Campaign—Although in some instances we unfortunately failed, yet upon the whole Heaven hath smiled on our Arms and crowned them with signal success; and we may upon the best grounds conclude, that by a spirited continuance of the measures necessary for our defense we shall finally obtain the end of our Warfare—Independence—Liberty and Peace—These are blessings worth contending for at every hazard…

Tomorrow being the day set apart by the Honorable Congress for public Thanksgiving and Praise; and duty calling us devoutly to express our grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us—The General directs that the army remain in its present quarters, and that the Chaplains perform divine service with their several Corps and brigades—And earnestly exhorts, all officers and soldiers, whose absence is not indispensably necessary, to attend with reverence the solemnities of the day.

George Washington, General Orders (March 1, 1778)

Their [the officers and soldiers] fortitude not only under the common hardships incident to a military life, but also under the additional sufferings to which the peculiar situation of these States have exposed them, clearly proved them worthy the enviable privilege of contending for the rights of human nature, the Freedom and Independence of their country.

Surely we who are free Citizens in arms engaged in a struggle for everything valuable in society and partaking in the glorious task of laying the foundation of an Empire, should scorn effeminately to shrink under those accidents and rigors of War which mercenary hirelings fighting in the cause of lawless ambition, rapine and devastation, encounter with cheerfulness and alacrity, we should not be merely equal, we should be superior to them in every qualification that dignifies the man or the soldier in proportion as the motive from which we act and the final hopes of our Toils, are superior to theirs. Thank Heaven! our Country abounds with provision & with prudent management we need not apprehend want for any length of time.

[B]ut soldiers! American soldiers! will despise the meanness of repining at such trifling strokes of adversity, trifling indeed when compared to the transcendent Prize which will undoubtedly crown their patience and perseverance, glory and freedom, peace and plenty to themselves and the community; the admiration of the world, the love of their country, and the gratitude of posterity.

[H]e [Washington] is convinced the faithful officers and soldiers associated with him in the great work of rescuing our country from bondage and misery will continue in the display of that patriotic zeal which is capable of smoothing every difficulty and vanquishing every obstacle.

George Washington, General Orders (March 14, 1778)

Homosexuality

At a General Court Martial whereof Coll Tupper was President (10th March 1778) Lieutt Enslin of Coll Malcom’s Regiment tried for attempting to commit sodomy, with John Monhort a soldier; Secondly, For Perjury in swearing to false Accounts, found guilty of the charges exhibited against him, being breaches of 5th Article 18th Section of the Articles of War and do sentence him to be dismiss’d the service with Infamy—His Excellency the Commander in Chief approves the sentence and with Abhorrence & Detestation of such Infamous Crimes orders Lieutt Enslin to be drummed out of Camp tomorrow morning by all the Drummers and Fifers in the Army never to return; The Drummers and Fifers to attend on the Grand Parade at Guard mounting for that Purpose.

George Washington, General Orders (April 12, 1778)

The Honorable Congress having thought proper to recommend to The United-States of America to set apart Wednesday the 22nd instant to be observed as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, that at one time and with one voice the righteous dispensations of Providence may be acknowledged and His Goodness and Mercy towards us and our Arms supplicated and implored—The General directs that this day also shall be religiously observed in the Army, that no work be done thereon and that the Chaplains prepare discourses suitable to the Occasion—The Funeral Honors at the Interment of officers are for the future to be confined to a solemn Procession of officers and soldiers in number suitable to the rank of the deceased with Reversed Arms; Firing on those occasions in Camp is to be abolished.

George Washington, General Orders (May 2, 1778)

The Commander in Chief directs that divine Service be performed every Sunday at 11 o’Clock in those Brigades to which there are Chaplains—those which have none to attend the places of worship nearest to them—It is expected that Officers of all Ranks will by their attendance set an Example to their men.

While we are zealously performing the duties of good Citizens and soldiers we certainly ought not to be inattentive to the higher duties of Religion—To the distinguished Character of Patriot, it should be our highest Glory to add the more distinguished Character of Christian—The signal Instances of providential Goodness which we have experienced and which have now almost crowned our labors with complete Success, demand from us in a peculiar manner the warmest returns of Gratitude and Piety to the Supreme Author of all Good…

No fatigue Parties to be employed on Sundays till further Orders.

George Washington, General Orders (May 5, 1778)

A New Ally

It having pleased the Almighty ruler of the Universe propitiously to defend the Cause of the United American-States and finally by raising us up a powerful Friend [France] among the Princes of the Earth to establish our liberty and Independence upon lasting foundations, it becomes us to set apart a day for gratefully acknowledging the divine Goodness and celebrating the important Event which we owe to his benign Interposition.

The several Brigades are to be assembled for this Purpose at nine o’ Clock tomorrow morning when their Chaplains will communicate the Intelligence contained in the Postscript to the Pennsylvania Gazette of the 2nd instant and offer up a thanksgiving and deliver a discourse suitable to the Occasion…

George Washington, General Orders (June 30, 1778)

The Men are to wash themselves this afternoon and appear as clean and decent as possible.

Seven o’clock this evening is appointed that We may publicly unite in thanksgivings to the supreme Disposer of human Events for the Victory which was obtained on Sunday over the Flower of the British Troops.

George Washington, To Brigadier General Thomas Nelson (August 20, 1778)

The Conspicuous Hand of Providence

The hand of Providence has been so conspicuous in all this, that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations—but—it will be time enough for me to turn preacher, when my present appointment ceases; and therefore, I shall add no more on the Doctrine of Providence.

George Washington, General Orders (April 12, 1779)

The Honorable the Congress having recommended it to the United States to set apart Thursday the 6th of May next to be observed as a day of fasting, humiliation and prayer, to acknowledge the gracious interpositions of Providence; to deprecate deserved punishment for our Sins and Ingratitude, to unitedly implore the Protection of Heaven; Success to our Arms and the Arms of our Ally—The Commander in Chief enjoins a religious observance of said day and directs the Chaplains to prepare discourses proper for the occasion; strictly forbidding all recreations and unnecessary labor.

George Washington, Circular to State Governments (May 22, 1779)

When we consider the rapid decline of our currency, the general temper of the times, the disaffection of a great part of the people, the lethargy that overspreads the rest, the increasing danger to the southern states, we cannot but dread the consequences of any misfortune in this quarter; and must feel the impolicy [sic] of trusting our security to a want of activity and enterprise in the enemy.

I thought it my duty to give an idea of its true state [the military] and to urge the attention of the states to a matter in which their safety and happiness are so interested. I hope a concern for the public good will be admitted as the motive and excuse of my importunity.

George Washington, General Orders (July 29, 1779)

Many and pointed orders have been issued against that unmeaning and abominable custom of Swearing, notwithstanding which, with much regret the General observes that it prevails, if possible, more than ever; His feelings are continually wounded by the Oaths and Imprecations of the soldiers whenever he is in hearing of them.

The Name of That Being, from whose bountiful goodness we are permitted to exist and enjoy the comforts of life is incessantly imprecated and profaned in a manner as wanton as it is shocking: For the sake therefore of religion, decency and order the General hopes and trusts that officers of every rank will use their influence and authority to check a vice, which is as unprofitable as it is wicked and shameful.

George Washington, Circular to State Governments (August 27, 1780)

I am under the disagreeable necessity of informing you that the army is again reduced to an extremity of distress for want of provision.

It has been no inconsiderable support of our cause to have had it in our power to contrast the conduct of our army with that of the enemy, and to convince the inhabitants that while their rights were wantonly violated by the British troops, by ours they were respected.

Although the troops have upon every occasion hitherto borne their wants with unparalleled patience, it will be dangerous to trust too often to a repetition of the causes of discontent.

George Washington, Circular to State Governments (October 18, 1780)

I am religiously persuaded, that the duration of the war, and the greatest part of the misfortunes and perplexities we have hitherto experienced are chiefly to be attributed to the system of temporary enlistments. Had we in the commencement raised an army for the war, such as was within the reach of the abilities of these States to raise and maintain, we should not have suffered those military checks which have so frequently shaken our cause, nor should we have incurred such enormous expenditures as have destroyed our paper currency, and with it all public credit.

After having lost two battles and Philadelphia in the following campaign for want of those numbers and that degree of discipline, which we might have acquired by permanent force in the first instance, in what a cruel and perilous situation did we again find ourselves in the winter of ’77, at Valley Forge, within a day’s march of the enemy, with a little more than a third of their strength, unable to defend our position, or retreat from it, for want of the means of transportation?

The prices of everything, men, provisions, etc., are raised to a height to which the revenues of no government, much less ours, would suffice. It is impossible the people can endure the excessive burden of bounties for annual drafts and substitutes increasing at every new experiment; whatever it might cost them once for all to procure men for the war, would be a cheap bargain.

Tis time we should get rid of an error, which the experience of all mankind has exploded, and which our own experience has dearly taught us to reject—the carrying on a war with militia, or, (which is nearly the same thing) temporary levies, against a regular, permanent and disciplined force. The idea is chimerical, and that we have so long persisted in it, is a reflection on the judgment of a nation so enlightened as we are, as well as a strong proof of the empire of prejudice over reason. If we continue in the infatuation, we shall deserve to lose the object we are contending for.

America has been almost amused out of her liberties.

It is as necessary to give Congress, the common head, sufficient powers to direct the common forces, as it is to raise an army for the war; but I should go out of my province to expatiate on civil affairs.

Our finances are in an alarming state of derangement. Public credit is almost arrived at its last stage. The people begin to be dissatisfied with the feeble mode of conducting the war, and with the ineffectual burthens imposed upon them, which though light in comparison with what other nations feel, are from their novelty heavy to them. They lose their confidence in government apace.

These circumstances conspire to show the necessity of immediately adopting a plan that will give more energy to government, more vigor and more satisfaction to the army. Without it we have everything to fear. I am persuaded of the sufficiency of our resources if properly directed.

The present crisis of our affairs appears to me so serious as to call upon me as a good citizen to offer my sentiments freely for the safety of the republic.

George Washington, Circular to New England State Governments (January 5, 1781)

The aggravated calamities and distresses that have resulted from the total want of pay for nearly twelve months, for want of clothing, at a severe season, and not infrequently the want of provisions are beyond description.

It is not within the sphere of my duty to make requisitions without the authority of Congress, from individual States. But at such a crisis, and circumstanced as we are, my own heart will acquit me, and Congress, and the States (eastward of this) whom for the sake of dispatch, I address, I am persuaded will excuse me when once for all I give it decidedly as my opinion that it is in vain to think an army can be kept together much longer under such a variety of sufferings as ours has experienced; and that unless some immediate and spirited measures are adopted to furnish at least three months’ pay to the troops in money that will be of some value to them, and at the same time ways and means are devised to cloth and feed them better (more regularly I mean), than they have been the worst than can befall us may be expected.

George Washington, Circular to State Governments (January 22, 1781)

The precise intention of the mutineers [troops from New Jersey] was not known, but their complaints and demands were similar to those of the Pennsylvanians.

Persuaded that without some decisive effort, at all hazards to suppress this dangerous spirit it would speedily infect the whole army. I have ordered as large a detachment as we could spare from these posts to march under Major General Howe with orders to compel the mutineers to unconditional submission; to listen to no terms while they were in a state of resistance, and on their reduction to execute instantly a few of the most active, and most incendiary leaders.

I dare not detail the risks we run from the present scantiness of supplies…I cannot but renew my solicitations with your State to exert every expedient for contributing to our immediate relief.

George Washington, General Orders (January 30, 1781)

The General is deeply sensible of the sufferings of the army. He leaves no expedient unessayed [unattempted] to relieve them, and he is persuaded Congress and the several States are doing everything in their power for the same purpose. But while we look to the public for the fulfillment of its engagements, we should do it with proper allowance for the embarrassments of public affairs. We began a contest for Liberty and Independence ill provided with the means for war, relying on our own patriotism to supply the deficiency…But it is our duty to bear present evils with fortitude, looking forward to the period when our country will have it more in its power to reward our services.

History is full of examples of armies suffering with patience extremities of distress which exceed those we have suffered, and this in the cause of ambition and conquest, not in that of the rights of humanity of their country, of their families, of themselves. Shall we who aspire to the distinction of a patriot army, who are contending for everything precious in society against everything hateful and degrading in slavery, shall we who call ourselves citizens discover less constancy and military virtue than the mercenary instruments of ambition?

George Washington, General Orders (March 11, 1783)

The Commander in Chief, having heard that a general meeting of the officers of the army was proposed to be held this day at the Newbuilding in an anonymous paper which was circulated yesterday by some unknown person, conceives (although he is fully persuaded that the good sense of the officers would induce them to pay very little attention to such an irregular invitation) his duty as well as the reputation and true interest of the army requires his disapprobation of such disorderly proceedings…

After mature deliberation, they [Washington and the senior officers] will devise what further measures ought to be adopted as most rational and best calculated to attain the just and important object in view [the officers and men getting paid.

George Washington, General Orders (March 23, 1781)

In answer to your request to be appointed Chaplain of the Garrison at Wyoming I have to observe; that there is no provision made by Congress for such an establishment; without which, I should not be at liberty to make any appointment of the kind, however necessary or expedient (in my opinion), or however I might be disposed to give every species of countenance and encouragement to the cultivation of Virtue, Morality, and Religion.

George Washington, General Orders (September 15, 1781)

The Commander in Chief takes the earliest Opportunity of testifying the satisfaction he feels on Joining the Army under the Command of Major General the Marquis de la Fayette with prospects which (under the smiles of Heaven) he doubts not will crown their toils with the most brilliant success—A conviction that the Officers and soldiers of this Army will still be activated by that true Martial spirit and thirst of Glory which they have already exhibited on so many trying occasions and under circumstances far less promising than the present affords him the most pleasing sensations.

George Washington, General Orders (October 20, 1781)

Divine Service is to be performed tomorrow in the several Brigades or Divisions.

George Washington, General Orders (April 22, 1782)

The United States in Congress assembled having been pleased by their Proclamation dated the 19th March last to appoint Thursday next the 25th Instant to be set apart as a day of Fasting humiliation and Prayer for certain special purposes therein mentioned: the same is to be Observed accordingly throughout the Army, and the different Chaplains will prepare Discourses Suited to the Several Objects enjoined by the said Proclamation.

George Washington, Office Orders (June 19, 1782)

That Divine Providence may shed its choicest blessings upon the King of France and his Royal Consort and favor them with a long, happy and glorious reign—that the Dauphin may live to inherit the virtues and the Crown of his Illustrious progenitors—that he may Reign over the hearts of a happy and generous people, and be among the happiest in his kingdom is our sincere and fervent wish.

George Washington, General Orders (February 15, 1783)

The New building being so far finished as to admit the troops to attend public worship therein after tomorrow, it is directed that divine Services should be performed there every Sunday by the several Chaplains of the New Windsor Cantonment in rotation and in order that the different brigades may have an opportunity of attending at different hours in the same day (whenever the weather and other circumstances will permit which the Brigadiers and Commandants of brigades must determine) the General recommends that the Chaplains should in the first place consult the Commanding officers of their Brigades to know what hour will be most convenient and agreeable for attendance that they will then settle the duty among themselves and report the results to the Brigadiers and Commandants of Brigades who are desired to give notice in their orders and to afford every aid and assistance in their power for the promotion of that public Homage and adoration which are due to the supreme being—who has through his infinite goodness brought our public Calamities and dangers (in all human probability) very near to a happy conclusion.

The Commander in Chief also desires and expects the Chaplains in addition to their public functions will in turn constantly attend the Hospitals and visit the sick—and while they are thus publicly and privately engaged in performing the sacred duties of their office they may depend upon his utmost encouragement and support on all occasions, and that they will be considered in a very respectable point of light by the whole Army.

Official Documents and Speeches (Commander in Chief, 1775-1783)

George Washington, Address to the Inhabitants of Canada (September 14, 1775) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

Friends and Brethren,

The unnatural Contest between the English Colonies and Great Britain, has now risen to such a Heighth [sic], that Arms alone must decide it. The Colonies, confiding in the Justice of their Cause, and the Purity of their Intentions, have reluctantly appealed to that Being, in whose Hands are all human Events. He has hitherto smiled upon their virtuous Efforts—The Hand of Tyranny has been arrested in its Ravages, and the British Arms which have shone with so much Splendor in every Part of the Globe, are now tarnished with Disgrace and Disappointment.—Generals of approved Experience, who boasted of subduing this great Continent, find themselves circumscribed within the Limits of a single City and its Suburbs, suffering all the Shame and Distress of a Siege. While the trueborn Sons of America, animated by the genuine Principles of Liberty and Love of their Country, with increasing Union, Firmness and Discipline repel every Attack, and despise every Danger.

Above all, we rejoice, that our Enemies have been deceived with Regard to you—They have persuaded themselves, they have even dared to say, that the Canadians were not capable of distinguishing between the Blessings of Liberty, and the Wretchedness of Slavery; that gratifying the Vanity of a little Circle of Nobility—would blind the Eyes of the People of Canada.—By such Artifices they hoped to bend you to their Views, but they have been deceived, instead of finding in you that Poverty of Soul, and Baseness of Spirit, they see with a Chagrin equal to our Joy, that you are enlightened, generous, and virtuous—that you will not renounce your own Rights, or serve as Instruments to deprive your Fellow Subjects of theirs.—Come then, my Brethren, unite with us in an indissoluble Union, let us run together to the same Goal.—We have taken up Arms in Defense of our Liberty, our Property, our Wives, and our Children, we are determined to preserve them, or die. We look forward with Pleasure to that Day not far remote (we hope) when the Inhabitants of America shall have one Sentiment, and the full Enjoyment of the Blessings of a free Government.

Incited by these Motives, and encouraged by the Advice of many Friends of Liberty among you, the Grand American Congress have sent an Army into your Province, under the Command of General Schuyler; not to plunder, but to protect you; to animate, and bring forth into Action those Sentiments of Freedom you have disclosed, and which the Tools of Despotism would extinguish through the whole Creation.—To co-operate with this Design, and to frustrate those cruel and perfidious Schemes, which would deluge our Frontiers with the Blood of Women and Children; I have detached Colonel Arnold into your Country, with a Part of the Army under my Command—I have enjoined upon him, and I am certain that he will consider himself, and act as in the Country of his Patrons, and best Friends. Necessaries and Accommodations of every Kind which you may furnish, he will thankfully receive, and render the full Value.—I invite you therefore as Friends and Brethren, to provide him with such Supplies as your Country affords; and I pledge myself not only for your Safety and Security, but for ample Compensation. Let no Man desert his Habitation—Let no one flee as before an Enemy. The Cause of America, and of Liberty, is the Cause of every virtuous American Citizen; whatever may be his Religion or his Descent, the United Colonies know no Distinction but such as Slavery, Corruption and arbitrary Domination may create. Come then, ye generous Citizens, range yourselves under the Standard of general Liberty—against which all the Force and Artifice of Tyranny will never be able to prevail.

George Washington, Speech to the Delaware Chiefs (May 12, 1779)1

You do well to wish to learn our arts and ways of life, and above all, the religion of Jesus Christ. These will make you a greater and happier people than you are. Congress will do everything they can to assist you in this wise intention.

George Washington, Circular to State Governments (June 8, 1783)2

Blessing or Curse

I think it a duty incumbent on me, to make this my last official communication, to congratulate you on the glorious events which Heaven has been pleased to produce in our favor…and to give my final blessing to that country, in whose service I have spent the prime of my life, for whose sake I have consumed so many anxious days and watchful nights, and whose happiness being extremely dear to me, will always constitute no inconsiderable part of my own…

[W]e shall have equal occasion to felicitate ourselves on the lot which Providence has assigned us, whether we view it in a natural, a political or moral point of light.

The Citizens of America, placed in the most enviable condition, as the sole Lords and Proprietors of a vast tract of 516 | 517 continent, comprehending all the various soils and climates of the World, and abounding with all the necessaries and conveniences of life, are now by the last satisfactory pacification, acknowledged to be possessed of absolute freedom and independency; they are, from this period, to be considered as the Actors on a most conspicuous theater, which seems to be peculiarly designated by Providence for the display of human greatness and felicity…Heaven has crowned all its other blessings, by giving a fairer opportunity for political happiness, than any other Nation has ever been favored with…The foundation of our Empire was not laid in the gloomy age of ignorance and superstition, but at an epocha when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined, than at any former period, the researches of the human mind, after social happiness, have been carried to a great extent, the treasures of knowledge, acquired by the labors of philosophers, sages and legislatures, through a long succession of years, are laid open for our use, and their collected wisdom may be happily applied in the establishment of our forms of government; the free cultivation of letters, the unbounded extension of commerce, the progressive refinement of manners, the growing liberality of sentiment, and above all, the pure and benign light of Revelation, have had a meliorating influence on mankind and increased the blessings of society. At this auspicious, the United States came into existence as a Nation, and if their citizens should not be completely free and happy, the fault will be entirely their own.

Such is our situation, and such are our prospects: but notwithstanding the cup of blessing [1 Cor. 10:16] is thus reached out to us, notwithstanding happiness is ours, if we have a disposition to seize the occasion and make it our own; yet, it appears to me there is an option still left to the United States of America, that it is in their choice, and depends upon their conduct, whether they will be respectable and prosperous, or contemptible, 517 | 518 and miserable as a nation; this is the time of their [the United States’] political probation, this is the moment when the eyes of the whole World are turned upon them, this is the moment to establish or ruin their national character forever, this is the favorable moment to give such a tone to our Federal Government, as will enable it to answer the ends of its institution, or this may be the ill-fated moment for relaxing the powers of the Union, annihilating the cement of the Confederation, and exposing us to become the sport of European politics, which may play one state against another to prevent their growing importance, and to serve their own interested purposes. For according to the system of policy the state shall adopt at this moment, they will stand or fall, and by their confirmation or lapse, it is yet to be decided, whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse [Deut. 11:26]: a blessing or a curse, not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn millions be involved… 518 | 521

[I]n the meantime, let an attention to the cheerful performance of their proper business, as individuals, and as members of society, be earnestly inculcated on the citizens of America, that will they strengthen the hands of government, and be happy under its protection: everyone will reap the fruit of his labors, everyone will enjoy his own acquisitions without molestation and without danger [Ps. 128:2].

In this this state of absolute freedom and perfect security, who will grudge to yield a very little of his property to support the common interest of society, and ensure the protection of government?…In what part of the continent shall we find any man, or body of men, who would not blush to stand up and propose measures, purposely calculated to rob the soldier of his stipend, and the public creditor of his due? And were it possible that such a flagrant instance of injustice could ever happen, would it not excite the general indignation, and tend to bring down upon the authors of such measures the aggravated vengeance of Heaven?… 521 | 522

[I]f there should be a refusal to comply with the requisitions for funds to discharge the annual interest of the public debts, and if that refusal should revive again all those jealousies and produce all those evils, which are now happily removed, Congress, who have in all their transaction shewn a great degree of magnanimity and justice, will stand justified in the sight of God and Man [Prov. 3:4; Luke 2:52; 2 Cor. 8:21], and the state alone which puts itself in opposition to the aggregate wisdom of the Continent, and follows such mistaken and pernicious councils, will be responsible for all the consequences… 522 | 524

It is, however, neither my wish or expectation, that the preceding observations should claim any regard, except so far as they shall appear to be dictated by a good intention, consonant to the immutable rules of Justice, calculated to produce a liberal system of policy, and founded on whatever experience may have been acquired by a long and close attention to public business… 524 | 526

I now make it my earnest prayer that God would have you and the State over which you preside in his holy protection, that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government, and to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for their brethren who have served in the field, and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy [Mic. 6:8], and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility, and pacific temper of mind which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion, [Jesus] and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things we can never hope to be a happy nation.

George Washington, Farewell Address to the Armies of the United States (November 2, 1783)3

The United States in Congress assembled, after giving the most honorable testimony to the merits of the federal armies, and presenting them with the thanks of their country for their long, eminent and faithful services, having thought proper, by their proclamation bearing date the 18th day of October last, to discharge such part of the troops as were engaged for the war, and to permit the officers on furlough to retire from service from and after to-morrow; which proclamation having been communicated in the public papers for the information and government of all concerned, it only remains for the Commander-in-chief to address himself once more, 542 | 543 and that for the last time, to the armies of the United States (however widely dispersed the individuals who compose them may be), and to bid them an affectionate, a long farewell.

But before the Commander-in-chief takes his final leave of those he holds most dear, he wishes to indulge himself a few moments in calling to mind a slight review of the past.

A contemplation of the complete attainment (at a period earlier than could have been expected) of the object, for which we contended against so formidable a power, cannot but inspire us with astonishment and gratitude. The disadvantageous circumstances on our part, under which the war was undertaken, can never be forgotten. The singular interposition of Providence in our feeble condition were such, as could scarcely escape the attention of the most unobserving; while the unparalleled perseverance of the Armies of the U[nited] States, through almost every possible suffering and discouragement for the space of eight long years, was little short of a standing miracle…

Every American officer and soldier must now console himself for any unpleasant circumstances, which may have occurred, by a recollection of the uncommon scenes in which he has been called to act no inglorious part, and the astonishing events of which he has been a witness; events which have seldom, if ever before, taken place on the stage of human action; nor can they probably ever happen again. For who has before seen a disciplined army formed at once from such raw materials? Who, that was not a witness, could imagine, that the most violent local prejudices 543 | 544 would cease so soon; and that men, who came from the different parts of the continent, strongly disposed by the habits of education to despise and quarrel with each other, would instantly become but one patriotic band of brothers? Or who, that was not on the spot, can trace the steps by which such a wonderful revolution has been effected, and such a glorious period put to all our warlike toils?

It is universally acknowledged, that the enlarged prospects of happiness, opened by the confirmation of our independence and sovereignty, almost exceeds the power of description. And shall not the brave men, who have contributed so essentially to these inestimable acquisitions, retiring victorious from the field of war to the field of agriculture, participate in all the blessings, which have been obtained? In such a republic, who will exclude them from the rights of citizens, and the fruits of their labors? In such a country, so happily circumstanced, the pursuits of commerce and the cultivation of the soil will unfold to industry the certain road to competence. To those hardy soldiers, who are actuated by the spirit of adventure, the fisheries will afford ample and profitable employment; and the extensive and fertile regions of the West will yield a most happy asylum to those, who, fond of domestic enjoyment, are seeking for personal independence. Nor is it possible to conceive, that any one of the United States will prefer a national bankruptcy, and a dissolution of the Union, to a compliance with the requisitions of Congress, and the payment of its just debts; so that the officers and soldiers may expect considerable assistance, in recommencing their civil occupations, from the sums due to them from the public, which must and will most inevitably be paid.

In order to effect this desirable purpose…it is earnestly recommended to all the troops, that, with strong attachments to the Union, they should carry with them into civil society the most conciliating dispositions, and that they should prove themselves not less virtuous and useful as citizens, than they have been persevering and victorious as soldiers… 544 | 545 [L]et it be remembered, that the unbiased voice of the free citizens of the United States has promised the just reward and given the merited applause. Let it be known and remembered, that the reputation of the federal armies is established beyond the reach of malevolence; and let a consciousness of their achievements and fame still incite the men, who composed them, to honorable actions; under the persuasion that the private virtues of economy, prudence, and industry, will not be less amiable in civil life, than the more splendid qualities of valor, perseverance, and enterprise were in the field. Everyone may rest assured that much, very much, of the future happiness of the officers and men, will depend upon the wise and manly conduct, which shall be adopted by them when they are mingled with the great body of the community. And, although the General has so frequently given it as his opinion in the most public and explicit manner, that, unless the principles of the Federal Government were properly supported, and the powers of the Union increased, the honor, dignity, and justice of the nation would be lost forever; yet he cannot help repeating, on this occasion, so interesting a sentiment, and leaving it as his last injunction to every officer and every soldier, who may view the subject in the same serious point of light, to add his best endeavors to those of his worthy fellow citizens towards effecting these great and valuable purposes, on which our very existence as a nation so materially depends… 545 | 546

He wishes more than bare professions were in his power; that he were really able to be useful to them all in future life. He flatters himself, however, they will do him the justice to believe, that whatever could with propriety be attempted by him has been done. And being now to conclude these his last public orders, to take his ultimate leave in a short time of the military character, and to bid a final adieu to the armies he has so long had the honor to command, he can only again offer in their behalf his recommendations to their grateful country, and his prayers to the God of Armies. May ample justice be done them here, and may the choicest of heaven’s favors, both here and hereafter, attend those who, under the divine auspices, have secured innumerable blessings for others.

George Washington, Address to Congress on Resigning Commission (December 23, 1783)

A “Holy Keeping”—Washington’s Resignation

I have now the honor of offering my sincere congratulations to Congress and of presenting myself before them to surrender into their hands the trust committed to me, and to claim the indulgence of retiring from the service of my country. Happy in the confirmation of our Independence and Sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the United States of becoming a respectable Nation, I resign with satisfaction the Appointment I accepted with diffidence. A diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task, which however was superseded by a confidence in the rectitude of our Cause, the support of the Supreme Power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven.

The Successful termination of the War has verified the most sanguine expectations, and my gratitude for the interposition of Providence, and the assistance I have received from my Countrymen, increases with every review of the momentous Contest…

I consider it an indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my Official life, by commending the Interests of our dearest Country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendence of them, to his holy keeping [Jude 1:24].

Having now finished the work assigned to me, I retire from the great theater of action; and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.

Official Documents and Speeches (President, 1789-1797)

George Washington, Undelivered First Inaugural Address: Fragments (April 30, 1789) | See Quote Archive | George Washington on Religion

We are this day assembled on a solemn and important occasion…not as a ceremony without meaning, but with a single reference to our dependence upon the Parent of all good…

If we had a secret resource of an nature unknown to our enemy, it was in the unconquerable resolution of our Citizens, the conscious rectitude of our cause, and a confident trust that we should not be forsaken by Heaven.

I solemnly assert and appeal to the searcher of hearts [Rom. 8:27] to witness the truth of it, that my leaving home to take upon myself the execution of this Office was the greatest personal sacrifice I have ever, in the course of my existence, been called upon to make.

In the next place, it will be recollected, that the Divine Providence hath not seen fit, that my blood should be transmitted or my name perpetuated by the endearing, though sometimes seducing channel of immediate offspring. I have no child for whom I could wish to make a provision—no family to build in greatness upon my Country’s ruins.

I feel the consolatory joys of futurity in contemplating the immense desarts [sic], yet untrodden by the foot of man, soon to become fair as the garden of God [Garden of Eden], soon to be animated by the activity of multitudes & soon to be made vocal with the praises of the Most High. [Ps. 7:17, et al] Can it be imagined that so many peculiar advantages, of soil & of climate, for agriculture & for navigation were lavished in vain—or that this Continent was not created and reserved so long undiscovered as a Theatre, for those glorious displays of Divine Munificence, the salutary consequences of which shall flow to another Hemisphere & extend through the interminable series of ages! Should not our Souls exult in the prospect! Though I shall not survive to perceive with these bodily senses, but a small portion of the blessed effects which our Revolution will occasion in the rest of the world; yet I enjoy the progress of human society & human happiness in anticipation.

Thus I have explained the general impressions under which I have acted: omitting to mention until the last, a principal reason which induced my acceptance. After a consciousness that all is right within and an humble hope of approbation in Heaven—nothing can, assuredly, be so grateful to a virtuous man as the good opinion of his fellow citizens.