Introduction

Jesus uses two terms in Scripture that are important to Catholic/protestant debates, and to a lesser extent Catholic/Eastern Orthodox debates. Those terms are “binding” and “loosing.” In this post, we’ll focus on the generic meaning of “binding and loosing” that both Catholics and Eastern Orthodox agree on, in contradistinction to protestants.

Roadmap

Our Roadmap is as follows:

- Our thesis is that the Jewish understanding of the term “binding and loosing” offers yet more support for the contention of this series that the authority of the Catholic Church is a fulfillment of the Jewish roots laid in the Old Testament. We will show this by:

- Covering the instances where this terminology appears in Scripture; then

- Examining the Jewish understanding of the terms “binding and loosing”;

- Then summarizing the conclusions we believe can be reached.

Binding and Loosing in Scripture

The first time Jesus uses this language is to St. Peter (Matt. 16:17-19):

17 And Jesus answered him, “Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. 18 And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. 19 I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Christ plainly promises here that the Keys will give St. Peter the authority to render decisions that Heaven will ratify. Thus, binding and loosing is somehow related to a general authority to render judgment among God’s people in a way that God stands behind.

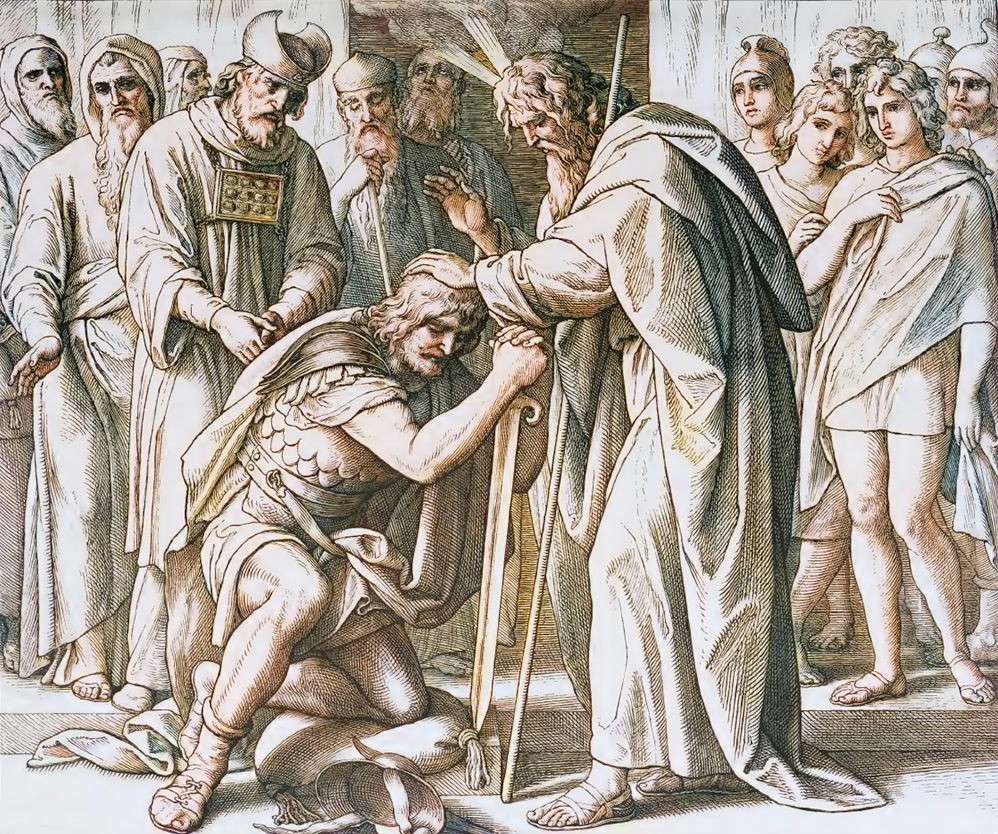

The only biblical parallel of “keys” investing someone with authority comes from Isaiah 22, where the prophet speaks of a man named Eliakim, who will replace another man named Shebna as the steward over the royal household. This passage likewise speaks of Eliakim receiving the keys of David, and opening/shutting in an authoritative manner (Isa. 22:20-24):

20 In that day I will call my servant Eliakim the son of Hilkiah, 21 and I will clothe him with your robe, and will bind your girdle on him, and will commit your authority to his hand; and he shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem and to the house of Judah. 22 And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. 23 And I will fasten him like a peg in a sure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father’s house. 24 And they will hang on him the whole weight of his father’s house, the offspring and issue, every small vessel, from the cups to all the flagons.

This Eliakim is indeed reported in several other places in the Bible as holding this position, which was akin to being Prime Minister of the kingdom. For example, he is described in Isaiah 36:3, 36:22, and 37:2, as well as 2 Kings 18:18 and 19:2 as being “over the household.” Thus, we see the only Old Testament parallel to Christ’s words in Matthew 16 to St. Peter likewise includes authority to govern that comes directly from God—in the one case, “he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open” (Isa. 22:22); and in the other, “whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matt. 16:19).

The second time Jesus refers to binding and loosing comes two chapters later. Here He addresses all the Apostles. While He doesn’t give them the Keys that He bestowed on St. Peter, He does give them all a similar authority to bind and loose (Matt. 18:15-20):

15 “If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother. 16 But if he does not listen, take one or two others along with you, that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. 17 If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector. 18 Truly, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven. 19 Again I say to you, if two of you agree on earth about anything they ask, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven. 20 For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.”

As He did with St. Peter, Jesus clearly situates binding and loosing within an ecclesial context here as well. If a Christian falls into sin, he must be corrected. If he fails to be corrected, he must be brought to the Church. And if he fails to be corrected by the Church, he must be cast out—presumably some form of excommunication. Only after laying out this process does Christ assert the authority by which the Apostles will be empowered to do this very thing: binding and loosing, rendering a judgment that Heaven itself will stand behind.

Jesus also refers to this authority existing among the scribes and Pharisees who “sit on Moses’ seat” (Matt. 23:1-4):

Then said Jesus to the crowds and to his disciples, 2 “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; 3 so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice. 4 They bind heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on men’s shoulders; but they themselves will not move them with their finger.

Ananias, the man who Jesus directed to receive Saul into the Church in Damascus, uses the same terminology of “binding” when speaking of the authority given by the High Priest to Saul to persecute Christians (Acts 9:11-14):

11 And the Lord said to him, “Rise and go to the street called Straight, and inquire in the house of Judas for a man of Tarsus named Saul; for behold, he is praying, 12 and he has seen a man named Ananias come in and lay his hands on him so that he might regain his sight.” 13 But Ananias answered, “Lord, I have heard from many about this man, how much evil he has done to thy saints at Jerusalem; 14 and here he has authority from the chief priests to bind all who call upon thy name.”

The Jewish Understanding of “Binding and Loosing”

So how would Jesus’s Jewish audience have understood His use of the term “binding and loosing”? Well, it turns out to be a very Catholic understanding, which is obvious from a natural reading of the text. In short, it is the authority exercised by men holding a God-ordained office to render a judgment that is ratified by Heaven itself.

Here is what the Jewish Encylopedia—originally published in 1906—says about the meaning of the term “binding and loosing”:

Rabbinical term for “forbidding and permitting.” The expression “asar” (to bind herself by a bond) is used in the Bible (Num. xxx. 3 et seq.) for a vow which prevents one from using a thing. It implies binding an object by a powerful spell in order to prevent its use (see Targ. to Ps. lviii. 6; Shab. 81b, for “magic spell”).

The encyclopedia article goes on to describe this authority among the Pharisees and the various schools of the Jews—the very thing Christ spoke of in Matthew 23:

The power of binding and loosing was always claimed by the Pharisees. Under Queen Alexandra, the Pharisees, says Josephus (“B J.” i, 5, § 2), “became the administrators of all public affairs so as to be empowered to banish and readmit whom they pleased, as well as to loose and to bind.” This does not mean that, as the learned men, they merely decided what, according to the Law, was forbidden or allowed, but that they possessed and exercised the power of tying or untying a thing by the spell of their divine authority, just as they could, by the power vested in them, pronounce and revoke an anathema upon a person. The various schools had the power “to bind and to loose”; that is, to forbid and to permit (Chag. 3b); and they could bind any day by declaring it a fast-day (Meg. Ta’an. xxii.; Ta’an. 12a; Yer. Ned. i. 36c, d).

This authority was nothing less than the authority of men to render judgment with the authority of God:

This power and authority, vested in the rabbinical body of each age or in the Sanhedrin (see Authority), received its ratification and final sanction from the celestial court of justice (Sifra, Emor, ix.; Mak. 23b).

The article goes on to explain this authority in its New Testament context:

In this sense Jesus, when appointing his disciples to be his successors, used the familiar formula (Matt. xvi. 19, xviii. 18). By these words he virtually invested them with the same authority as that which he found belonging to the scribes and Pharisees who “bind heavy burdens and lay them on men’s shoulders, but will not move them with one of their fingers”; that is, “loose them,” as they have the power to do (Matt. xxiii. 2-4). In the same sense, in the second epistle of Clement to James II. (“Clementine Homilies,” Introduction), Peter is represented as having appointed Clement as his successor, saying: “I communicate to him the power of binding and loosing so that, with respect to everything which he shall ordain in the earth, it shall be decreed in the heavens; for he shall bind what ought to be bound and loose what ought to be loosed as knowing the rule of the church.” Quite different from this Judaic and ancient view of the apostolic power of binding and loosing is the one expressed in John xx. 23, where Jesus is represented as having said to his disciples after they had received the Holy Spirit: “Whosesoever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them; and whosesoever sins ye retain, they are retained.” It is this view which, adopted by Tertullian and all the church fathers, invested the head of the Christian Church with the power to forgive sins, the “clavis ordinis,” “the key-power of the Church.”

In other words, the Jewish understanding of the terms “bind and loose” is essentially the same as, or compatible with the Catholic understanding of the authority given to the Apostles and their successors to teach and govern the Church with God’s authority and ratification.