Introduction

In the summer of 2017, the trajectory of my life changed forever, thanks to the writings of a Church Father who knew the Apostles. His name was St. Ignatius of Antioch. He has since become my patron saint, and I affectionately call him “St. Ignatius the Red Pill.”

This two-part series explains why.

The Roadmap

Our Roadmap for this two-part series is as follows:

- Our thesis is that the words of St. Ignatius of Antioch, a disciple and companion of the Apostles, written barely 75 years after the Ascension of Our Lord, are astoundingly Catholic, and thus strong evidence of the ancient and apostolic origin of the Catholic Faith. We’ll show this in two parts as follows:

- In Part 1 (this article), we will tell the story about how we discovered St. Ignatius of Antioch; followed by a brief biographical overview of the saint and martyr; followed by relevant quotations from five of his letters that reveal profoundly Catholic beliefs about multiple topics, especially apostolic succession, the priesthood, the Eucharist, as well as the unique name of the one true Church (hint: it’s “the Catholic Church”). For Part 1, we’ll quote from the following letters: Letter to the Ephesians, Letter to the Trallians, and Letter to the Smyrnaeans.

- In Part 2, we’ll dive into the remaining three letters of St. Ignatius: the Letter to the Philadelphians, Letter to the Romans, and Letter to St. Polycarp. Also, given that some protestants (fortunately a minority) have gone so far as to doubt St. Ignatius even existed (or that his writings were later forgeries), we will cover some of the ancient testimony affirming the existence of St. Ignatius and his writings, specifically from: St. Polycarp, St. Irenaeus of Lyon, Origen, Eusebius of Caesarea, St. Athanasius, St. Jerome, and St. John Chrysostom.

- We will conclude Part 2 with a summary of why St. Ignatius of Antioch was truly a “red pill” witness to the reality of the Catholic Faith to me as a protestant.

How I Discovered St. Ignatius of Antioch, the “Red Pill”

I still remember when it happened. It was June 2017, and my “38 Volume Set” of the Church Fathers had finally arrived. I had seen this set for many years, and, being a bibliophile—and thus inherently desirous of multi-volume sets of books—I wanted to get it. I had just finished law school, and was working full-time at the Museum of the Bible. After finishing a huge Bible project I had been working on as Senior Editor, and was later published as the Global Impact Bible, my boss told me that everyone at the Museum was focused on getting its main building in Washington, DC open that coming November. He told me to research whatever I wanted, and they would make it into exhibits afterward. This was around May 2017.

For someone who loved the Bible, loved history, and loved to read, this was music to my ears. So I figured I would get that 38 volume set I had seen for so many years.

Truth be told, all I expected to find was Christians pretty much like me, with many inspiring martyrdom stories. I had zero intention of finding the Catholic Faith and Church. While I had been struggling with various aspects of protestant theology for many years, I did not think of this struggle as being with “protestantism,” per se, so much as simply trying to work through various questions I had about my own Christianity.

The massive set of books finally arrived. It was June or July of 2017. I opened Volume 1 of my new Church Fathers set, which contained the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, or those Fathers who knew, and/or were closest in time to the Apostles, and thus the very origins of the Church.

One of the first names that appeared was Ignatius of Antioch, and especially upon learning about his life, I was absolutely stunned by his words. It was truly a life-changing “Red Pill” moment. For those who are unfamiliar with this term, it comes from the early 2000’s movie The Matrix. The main character is given a choice between two pills: blue, and red. The blue pill will allow him to remain in a fantasy world he finds more pleasant and livable, but is built on lies and falsehoods. But the red pill will show him the truth, even though it is less pleasant.

St. Ignatius was a “red pill” for one simple reason: what he said was astoundingly Catholic. Things I had been told for years were “traditions of men” made up centuries or millennia later were right here, on the lips of a man who knew the Apostles, was ordained by them, and was martyred for the faith. As protestants, we prided ourselves on supposedly chipping back on the “traditions of men” and man-made barnacles that had supposedly encrusted the church, taking us back to a pristine primitive age that, we claimed, was “biblical.” But when I read the writings of this man who was not only from that age, but knew the Apostles, he was anything but protestant. I could no longer fall back on explanations like “1,500 years of built-up traditions of men,” “Constantine,” “paganism infected the Church,” “wealth and power caused corruption,” and other reasons I had heard throughout my life from various protestant sects (as well as many atheists, ironically) to justify despising the Catholic Church and its so-called doctrinal and moral corruption.

In short, the writings of St. Ignatius of Antioch cut right through all the protestant propaganda I’d been given much of my life, and cut to the core of what Christianity was. For the first time in my life, I was confronted with the undeniable reality that the earliest Christians were remarkably, clearly, and ominously (for me, at the time) Catholic. There wasn’t a shred of anything uniquely protestant in his letters. That led me to the disturbing conclusion that if the Catholic Church was wrong, then it had been wrong not since the medieval period, but since the days of the Apostles. And if that was true, then I was confronted with the prospect that either my protestantism was true, or Christians had been wrong about their faith from basically the beginning–which, in my mind, made Christianity an unserious and farcical religion.

St. Ignatius: Biographical Overview

The reason why St. Ignatius of Antioch was so powerful was not only because of when he wrote, but who he was. He simply could not be dismissed.

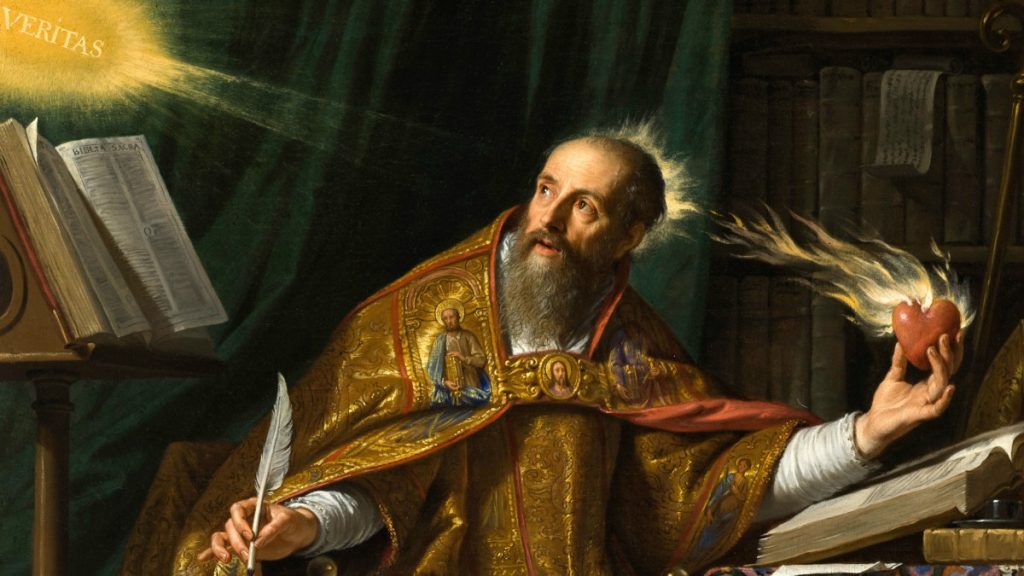

St. Ignatius was a disciple of the Apostles, and a bishop of Antioch. He was, in fact, ordained by St. Peter, and was his second successor as bishop of the church of Antioch. For reasons we don’t fully know, he was arrested by the Romans, and escorted from Syria to Rome, where he was executed. The earliest accounts say he was martyred in the Colosseum, eaten by wild beasts–something his own letters imply as well (perhaps he was told by his Roman escorts that he would be food for beasts as entertainment in Rome).

Along the journey, he wrote seven letters: six to the churches in Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Smyrna, Philadelphia, and Rome; and one to his friend, fellow companion of the Apostles, bishop, and later martyr, St. Polycarp of Smyrna. These letters, written around AD 107 during the persecution of Emperor Trajan (who reigned from 98-117), offer remarkable evidence of a man who was not only saintly, but believed in the Catholic Faith and Church.

There are also a great many testimonies to the life and martyrdom of St. Ignatius, which we’ll cover in Part 2.

Let’s now begin our dive into his letters.

Letter to the Ephesians

We’ll begin with St. Ignatius’s letter to the Ephesians.

As he often did, St. Ignatius begins by addressing only those in Ephesus who remain obedient to their bishop, an office he believed was established by Christ Himself (§1):

I received, therefore, your whole multitude in the name of God, through Onesimus, a man of inexpressible love, and your bishop in the flesh, whom I pray you by Jesus Christ to love, and that you would all seek to be like him. And blessed be He who has granted to you, being worthy, to obtain such an excellent bishop.

He likewise salutes the deacon and priests of the church, asserting that the Scriptural command to be of “the same mind” could only be fulfilled by obeying the hierarchy (bishops, priests, deacons) of the Church (§2):

As to my fellow-servant Burrhus, your deacon in regard to God and blessed in all things, I beg that he may continue longer, both for your honor and that of your bishop…It is therefore befitting that you should in every way glorify Jesus Christ, who hath glorified you, that by a unanimous obedience “you may be perfectly joined together in the same mind, and in the same judgment, and may all speak the same thing concerning the same thing” (1 Cor. 1:10) and that, being subject to the bishop and the presbytery, you may in all respects be sanctified.

In the third section, St. Ignatius again exhorts the Ephesians to unity, and this time connects it with not just the local bishop, but all the bishops around the world (§3):

[I]nasmuch as love suffers me not to be silent in regard to you, I have therefore taken upon me first to exhort you that you would all run together in accordance with the will of God. For even Jesus Christ, our inseparable life, is the [manifested] will of the Father; as also bishops, settled everywhere to the utmost bounds [of the earth], are so by the will of Jesus Christ.

From this passage we can see that St. Ignatius understood the Church as a unified entity did not exist merely at the local level, but also the universal (i.e. “Catholic”) level. This is confirmed by numerous other passages throughout his letters.

In the fourth section, St. Ignatius again affirms the necessity of obedience to the bishop and the priesthood, asserting that maintaining unity is necessary to enjoy communion with God (§4):

Wherefore it is fitting that you should run together in accordance with the will of your bishop, which thing also you do. For your justly renowned presbytery, worthy of God, is fitted as exactly to the bishop as the strings are to the harp. Therefore in your concord and harmonious love, Jesus Christ is sung. And do you, man by man, become a choir, that being harmonious in love, and taking up the song of God in unison, you may with one voice sing to the Father through Jesus Christ, so that He may both hear you, and perceive by your works that you are indeed the members of His Son. It is profitable, therefore, that you should live in an unblameable unity, that thus you may always enjoy communion with God.

In the fifth section, St. Ignatius goes on to describe the unity of the Church being centered around “the altar” from which Christians receive “the bread of God.” This is undoubtedly a reference to the Eucharist given similar descriptions in his other letters. As we will see, St. Ignatius described the Eucharist in astoundingly Catholic terms. Even this one, “bread of God,” necessarily implies that the Eucharist is not simply the bread and wine brought to the altar by men, but is in some sense transformed into a gift that we received from God Himself. Hence “bread of God.” Likewise, by describing the locus of Christian worship as an “altar,” it was clear that this worship was in some sense also a “sacrifice.” The idea that the Eucharist was the center of Christian worship, and that this worship was “sacrificial” in nature, was simply not part of my protestant framework–though I knew it was very much part of the Catholic one.

In the same section, St. Ignatius again emphasized the importance of obeying the bishop to maintaining unity, compared this with the unity between Christ and the Father, and declared that those who separated or gathered apart from the bishop—which he equated with the Church itself—were condemned. To obey God, he says, requires obeying the bishop (§5):

For if I in this brief space of time, have enjoyed such fellowship with your bishop—I mean not of a mere human, but of a spiritual nature—how much more do I reckon you happy who are so joined to him as the Church is to Jesus Christ, and as Jesus Christ is to the Father, that so all things may agree in unity! Let no man deceive himself: if anyone be not within the altar, he is deprived of the bread of God [the Eucharist]. For if the prayer of one or two possesses such power [Matt. 18:19], how much more that of the bishop and the whole Church! He, therefore, that does not assemble with the Church, has even by this manifested his pride, and condemned himself. For it is written, “God resists the proud” (Prov. 3:34; cf. Jas. 4:6; 1 Pet. 5:5). Let us be careful, then, not to set ourselves in opposition to the bishop, in order that we may be subject to God.

In the sixth section, St. Ignatius goes on to say that the bishop is the one God has set over His household, and that he should be treated as we would treat Christ Himself in order to avoid the sectarianism of heresy. The name of the bishop of Ephesus is Onesimus, and it is believed by some that he was the same Onesimus on whose behalf St. Paul wrote his letter to Philemon when Onesimus was still his slave. He is also believed to have been the successor of St. Timothy, who had originally been ordained by St. Paul (§6):

Now the more anyone sees the bishop keeping silence, the more ought he to revere him. For we ought to receive everyone whom the Master of the house sends to be over His household [Matt. 24:25], as we would do Him that sent him. It is manifest, therefore, that we should look upon the bishop even as we would upon the Lord Himself. And indeed Onesimus himself greatly commends your good order in God, that you all live according to the truth, and that no sect [heresy] has any dwelling-place among you. Nor, indeed, do you hearken to anyone rather than to Jesus Christ speaking in truth.

In the seventh section, St. Ignatius had harsh words for heretics who do not submit to the bishop (§7):

For some are in the habit of carrying about the name [of Jesus Christ] in wicked guile, while yet they practice things unworthy of God, whom you must flee as you would wild beasts. For they are ravening dogs, who bite secretly, against whom you must be on your guard, inasmuch as they are men who can scarcely be cured. There is one Physician who is possessed both of flesh and spirit; both made and not made; God existing in flesh; true life in death; both of Mary and of God; first possible and then impossible—even Jesus Christ our Lord.

In the ninth section, he then praises the Ephesians for not listening to the false doctrines of heretics (§9):

Nevertheless, I have heard of some who have passed on from this to you, having false doctrine, whom you did not suffer to sow among you, but stopped your ears, that you might not receive those things which were sown by them, as being stones of the temple of the Father, prepared for the building of God the Father, and drawn up on high by the instrument of Jesus Christ, which is the cross, making use of the Holy Spirit as a rope, while your faith was the means by which you ascended, and your love the way which led up to God.

In section 13, St. Ignatius likewise commends the Ephesians for their frequent gatherings, which he said destroys the power of Satan (§13):

Take heed, then, often to come together to give thanks to God, and show forth His praise. For when you assemble frequently in the same place, the powers of Satan are destroyed, and the destruction at which he aims is prevented by the unity of your faith. Nothing is more precious than peace, by which all war, both in heaven and earth, is brought to an end.

Once more, I was struck by St. Ignatius’s emphasis on unity–a lack of which deeply disturbed me as a protestant for many years (and which I know disturbs many protestants to this day, given its blatant contradiction of clear and repeated commands of Scripture). If indeed unity “destroys the power of Satan,” as St. Ignatius said, then the uncomfortable conclusion I had to reach was that our lack of unity as protestants had done the opposite: it had given Satan a beachhead from which to expand his power.

In the sixteenth section, St. Ignatius once more warns the Ephesians against heresy, declaring that heretics will go into the everlasting fire of Hell (§16):

Do not err, my brethren. Those that corrupt families [false teachers] shall not inherit the kingdom of God. If, then, those who do this as respects the flesh have suffered death, how much more shall this be the case with anyone who corrupts by wicked doctrine the faith of God, for which Jesus Christ was crucified! Such an one becoming defiled [in this way], shall go away into everlasting fire, and so shall every one that hearkens unto him.

Reading this as a protestant naturally raised all sorts of questions: who defines what is “heresy”? I had heard countless people from different denominations–good, virtuous, and well-educated people–accuse other protestants of heresy, who often returned the accusation. Both of them made this claim based on “Scripture.” But who was right? Without an objective authority to umpire the dispute, all we had were disputants throwing accusations at one another, with no “court,” so to speak, to resolve our dispute. St. Ignatius here, and everywhere else, is clear that the Church is that “court,” and the bishops–those who have succeeded from the Apostles–are those judges. For him, the essence of heresy and schism was a separation from the teaching and authority of the bishops. Did he address every possible question about this arrangement? No. He was, after all, writing short letters while on his way to his own death. But the letters he did leave us are quite clear: there is a visible Church governed by the successors of the Apostles, the bishops, and those under their charge: priests, and deacons. To separate from them was never licit for any Christian. As he makes clear in this and other letters, without them, and the Eucharistic altar over which they preside and from which Christian unity is fed, there is simply no “church” to speak of.

In section 17, St. Ignatius then makes an interesting assertion about the immortality Christ has breathed into the Church. It appears that he considered the visible Church governed by the bishops as not only the place of true doctrine, but as immortal. While the manner in which he speaks is quite general, it aligns with Catholic teaching about the infallibility and indefectibility of the Church (§17):

For this end did the Lord suffer the ointment to be poured upon His head, that He might breathe immortality into His Church. Be not you anointed with the bad odor of the doctrine of the prince of this world [heresies]; let him not lead you away captive from the life which is set before you. And why are we not all prudent, since we have received the knowledge of God, which is Jesus Christ? Why do we foolishly perish, not recognizing the gift which the Lord has of a truth sent to us?

St. Ignatius does not once countenance another constitution for the Church than that which he lays out. So if it is this Church into which Christ has breathed “immortality,” then there is no scenario in which a Christian could ever licitly separate from it. It will never die, after all, for this Church is not merely the construct of man, but has been established and built by God Himself. This idea of an immortal, visible, united Church, governed by men who succeeded directly from the Apostles, was completely foreign to my ideas, and indeed the reality I lived in, as a protestant.

In his conclusion, section 20, St. Ignatius once again emphasized the necessity of obedience to the bishop and priests. He asserts this is the key to maintaining the unity of faith, a unity which is represented in the sharing of the one Eucharist (the “bread of God” he spoke of earlier), which he calls the “medicine of immortality” and “antidote” to death—a striking echo of Christ’s words in John 6:53-54: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.” He wrote as follows (§20):

If Jesus Christ shall graciously permit me through your prayers, and if it be His will, I shall, in a second little work which I will write to you, make further manifest to you [the nature of] the dispensation of which I have begun [to treat], with respect to the new man, Jesus Christ, in His faith and in His love, in His suffering and in His resurrection. Especially [will I do this] if the Lord make known to me that you come together man by man in common through grace, individually, in one faith, and in Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David according to the flesh, being both the Son of man and the Son of God, so that you obey the bishop and the presbytery with an undivided mind, breaking one and the same bread [the Eucharist], which is the medicine of immortality, and the antidote to prevent us from dying, but [which causes] that we should live forever in Jesus Christ.

From his Letter to the Ephesians, we can see that St. Ignatius believed:

- The episcopacy and priesthood were established by Christ, and are owed obedience;

- Obeying the priesthood is essential to avoiding heresy and schism, which are damnable;

- The priesthood presides over the Church’s unity through the altar upon which the “bread of God” is offered;

- Christ has bestowed immortality on the visible Church;

- The unity of the Church is represented by communion in the “bread of God,” the “medicine of immortality,” and the “antidote” against death, which is the Eucharist.

Letter to the Magnesians

St. Ignatius wrote another letter to the church in Magnesia, a Greek city located on what is today the southwest coast of Turkey. Like his other letters, this one contains exceptionally strong language about the authority of the bishop and the priesthood.

In the first section, St. Ignatius offers an interesting prayer petition, namely for the “union both of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ” (§1):

Having been informed of your godly love, so well-ordered, I rejoiced greatly, and determined to commune with you in the faith of Jesus Christ. For as one who has been thought worthy of the most honorable of all names, in those bonds which I bear about, I commend the Churches, in which I pray for a union both of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ, the constant source of our life, and of faith and love, to which nothing is to be preferred, but especially of Jesus and the Father, in whom, if we endure all the assaults of the prince of this world, and escape them, we shall enjoy God.

Given his exhortations regarding the Eucharist, it seems that what St. Ignatius could mean by “union both of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ” is that those who have been spiritually reborn in baptism should maintain the unity of Christ’s body, the Church, which is symbolized, effected, and epitomized by the Eucharist. By offering a prayer that such union be maintained in the churches, he is acknowledging the unfortunate reality that regenerated believers can–as he so often warns against–fall into heresy and schism, either receiving the Eucharist unworthily, or departing from it altogether. They thereby separate the union of the “flesh” and “spirit” of Christ: the “spirit” given for regeneration in baptism, and the “flesh” given from the altar in the Eucharist. Once more, this strikingly visible, sacramental notion of Church unity was foreign to me as a protestant–both theologically, and in my day-to-day life.

In the second section, St. Ignatius then proceeds to greet the church of Magnesia in the persons of their bishop, priests, and deacons (§2):

Since, then, I have had the privilege of seeing you, through Damas your most worthy bishop, and through your worthy presbyters Bassus and Apollonius, and through my fellow-servant the deacon Sotio, whose friendship may I ever enjoy, inasmuch as he is subject to the bishop as to the grace of God, and to the presbytery as to the law of Jesus Christ, [I now write to you].

This apostolic constitution of the Church seems to be everywhere assumed by St. Ignatius, who never countenances an alternative arrangement of church government. The idea that local churches can differ in their essential forms of government and be equally “Christian”–something I took for granted as a protestant–was nowhere in his thinking.

In the third section, St. Ignatius emphasized the need to obey the bishop because of his office, no matter how young (very similar to St. Paul’s exhortation to St. Timothy). He also makes clear that such obedience is not a matter of obeying man, but God Himself (§3):

Now it becomes you also not to treat your bishop too familiarly on account of his youth, but to yield him all reverence, having respect to the power of God the Father, as I have known even holy presbyters do, not judging rashly, from the manifest youthful appearance [of your bishop], but as being themselves prudent in God, submitting to him, or rather not to him, but to the Father of Jesus Christ, the bishop of us all. It is therefore fitting that you should, after no hypocritical fashion, obey [your bishop], in honor of Him who has willed us [so to do], since he that does not so deceives not [by such conduct] the bishop that is visible, but seeks to mock Him that is invisible. And all such conduct has reference not to man, but to God, who knows all secrets.

In the fourth section, St. Ignatius once more emphasizes obedience, asserting that it is essential to being Christian (§4):

It is fitting, then, not only to be called Christians, but to be so in reality: as some indeed give one the title of bishop, but do all things without him. Now such persons seem to me to be not possessed of a good conscience, seeing they are not steadfastly gathered together according to the commandment.

In section 5, he then compares obedience to life, and disobedience to death, saying obedience is required for those “of God,” whereas disobedience is emblematic of “the world” (§5):

Seeing, then, all things have an end, these two things are simultaneously set before us—death and life; and everyone shall go to his own place. For as there are two kinds of coins, the one of God, the other of the world, and each of these has its special character stamped upon it, [so is it also here]. The unbelieving are of this world; but the believing have, in love, the character of God the Father by Jesus Christ, by whom, if we are not in readiness to die into His passion, His life is not in us.

In section 6, St. Ignatius once more exhorts the Magnesians to obedience, saying the bishop stands in the place of God, the presbyters (priests) in the assembly of the apostles, and includes the deacons in “the ministry of Jesus Christ,” once more covering all three essential grades of Holy Orders that continue to be present in the Catholic Church to this day (§6):

Since therefore I have, in the persons before mentioned, beheld the whole multitude of you in faith and love, I exhort you to study to do all things with a divine harmony, while your bishop presides in the place of God, and your presbyters in the place of the assembly of the apostles, along with your deacons, who are most dear to me, and are entrusted with the ministry of Jesus Christ, who was with the Father before the beginning of time, and in the end was revealed. Do you all then, imitating the same divine conduct, pay respect to one another, and let no one look upon his neighbor after the flesh, but do you continually love each other in Jesus Christ. Let nothing exist among you that may divide you; but be you united with your bishop, and those that preside over you, as a type and evidence of your immortality.

Once more, I was stunned by how strongly St. Ignatius asserted that being united to one’s bishop is intrinsic to the Christian faith. Indeed, he argued it was a reflection of the “immortality” to which the Christian was called, an immortality based on unity, which unity was itself a reflection of the unity of the Triune God (a connection made by Christ Himself in places like John 17).

This naturally leads to St. Ignatius comparing this obedience and union with the bishop and priesthood to Christ’s obedience to and union with the Father within the Trinity, emphasizing that the Word Himself did not operate according to His own will, but that of the Father. One cannot help but think of Christ’s prayer for the unity of the Apostles by likewise comparing their unity to His own with the Father (John 17:11): “Holy Father, keep them in thy name, which thou hast given me, that they may be one, even as we are one.” St. Ignatius insists that this analogy of the Trinity is the basis of the unity of the Church, referencing the “one altar” (no doubt the Eucharistic sacrifice), the “one temple of God,” and decrying schism (§7):

As therefore the Lord did nothing without the Father, being united to Him, neither by Himself nor by the apostles, so neither do you anything without the bishop and presbyters. Neither endeavor that anything appear reasonable and proper to yourselves apart; but being come together into the same place, let there be one prayer, one supplication, one mind, one hope, in love and in joy undefiled. There is one Jesus Christ, than whom nothing is more excellent. Do you therefore all run together as into one temple of God, as to one altar, as to one Jesus Christ, who came forth from one Father, and is with and has gone to one.

In section 13, he concludes the body of the letter by once more emphasizing that obeying the priesthood reflected Christ obeying the Father, and the Apostles obeying Christ (§13):

Study, therefore, to be established in the doctrines of the Lord and the apostles, that so all things, whatsoever you do, may prosper both in the flesh and spirit; in faith and love; in the Son, and in the Father, and in the Spirit; in the beginning and in the end; with your most admirable bishop, and the well-compacted spiritual crown of your presbytery, and the deacons who are according to God. Be you subject to the bishop, and to one another, as Jesus Christ to the Father, according to the flesh, and the apostles to Christ, and to the Father, and to the Spirit; that so there may be a union both fleshly and spiritual.

Once more, we see St. Ignatius argue that Christian unity results from the union of the “spirit” and “flesh” of Christ, the “spirit” having been received in baptism, and the “flesh” in the Eucharist. To be outside of this unity is gravely sinful.

In short, in this letter, like the others, St. Ignatius affirms:

- The three-fold clerical office (bishop, priest, and deacon)

- The necessity of obeying the clergy (especially the bishop);

- That such obedience is a reflection of the unity of the Trinity, Christ’s obedience to the Father, and the Apostles’ obedience to Christ;

- The necessity of maintaining the union between the “spirit” and “flesh” of Christ (undoubtedly referring to the union between the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist); and that

- Christian unity was centered around “one altar” offering one prayer in the “one temple of God,” the Church.

Letter to the Trallians

The same beliefs are likewise readily apparent in St. Ignatius’s Letter to the Trallians. Tralles was a Greek city located in what is today western Turkey (the modern city is named Aydin).

In the first section, as in so many of his other letters, he refers to the church’s bishop (§1):

I know that you possess an unblameable and sincere mind in patience, and that not only in present practice, but according to inherent nature, as Polybius your bishop has shown me, who has come to Smyrna by the will of God and Jesus Christ, and so sympathized in the joy which I, who am bound in Christ Jesus, possess, that I beheld your whole multitude in him. Having therefore received through him the testimony of your good-will, according to God, I gloried to find you, as I knew you were, the followers of God.

In the second section, he emphasizes obedience to the bishop in ways we have already seen, as well as to deacons, who he says administer the “mysteries of Jesus Christ,” a clear reference to sacraments of some kind (§2):

For, since you are subject to the bishop as to Jesus Christ, you appear to me to live not after the manner of men, but according to Jesus Christ, who died for us, in order, by believing in His death, you may escape from death. It is therefore necessary that, as you indeed do, so without the bishop you should do nothing, but should also be subject to the presbytery, as to the apostle of Jesus Christ, who is our hope, in whom, if we live, we shall [at last] be found. It is fitting also that the deacons, as being [the ministers] of the mysteries of Jesus Christ, should in every respect be pleasing to all. For they are not ministers of meat and drink, but servants of the Church of God. They are bound, therefore, to avoid all grounds of accusation [against them], as they would do fire.

In the third section, St. Ignatius compares the ministers of the Church to the ancient Sanhedrin–the religious authority of the ancient Israelites–again asserting that they are appointed by Christ Himself and bear His authority, saying apart from them, “there is no Church” (§3):

In like manner, let all reverence the deacons as an appointment of Jesus Christ, and the bishop as Jesus Christ, who is the Son of the Father, and the presbyters as the Sanhedrin of God, and assembly of the apostles. Apart from these, there is no Church. Concerning all this, I am persuaded that you are of the same opinion. For I have received the manifestation of your love, and still have it with me, in your bishop, whose very appearance is highly instructive, and his meekness of itself a power; whom I imagine even the ungodly must reverence, seeing they are also pleased that I do not spare myself.

This was another one of those lines that shocked me as a protestant. Neither I, nor any other protestant sect I knew of, possessed what St. Ignatius said we needed to have in order to even be a “church” (I say this in light of some of his words we have not yet examined, which describe the Eucharist in a way no protestant sect of any kind describes it). That meant that according to a disciple of the Apostles, a man who was ordained by St. Peter, and died as a martyr in Rome, I had never been part of a real “church” in my entire life. To communicate how shocking this was to me would be difficult indeed. My entire framework for being Christian was being destroyed. If what St. Ignatius was saying was true, then either I was deeply wrong about the nature of Christianity, or he was–and it seemed pretty absurd to think I had the advantage in that contest.

In the sixth section, St. Ignatius offered a very strong warning against heresy. He was deeply concerned about false doctrines, and believed the surest guarantee of true doctrine was communion with the priesthood of the Church (§6):

I therefore, yet not I, but the love of Jesus Christ, entreat you that you use Christian nourishment only, and abstain from herbage of a different kind; I mean heresy. For those [that are given to this] mix up Jesus Christ with their own poison, speaking things which are unworthy of credit, like those who administer a deadly drug in sweet wine, which he who is ignorant of does greedily take, with a fatal pleasure leading to his own death.

In section 7, he makes the connection between true doctrine, and obedience to the bishop, explicit. He also, yet again, connects obedience to the bishop (and other ministers) with Eucharistic communion (by his reference to “the altar”), making it clear that in his mind, magisterial authority and the Eucharist are intimately connected (§7):

Be on your guard, therefore, against such persons. And this will be the case with you if you are not puffed up, and continue in intimate union with Jesus Christ our God, and the bishop, and the enactments of the apostles. He that is within the altar is pure, but he that is without is not pure; that is, he who does anything apart from the bishop, and presbytery, and deacons, such a man is not pure in his conscience.

In section 11, he once more condemned heresy (§11):

Flee, therefore, those evil offshoots [of Satan], which produce death-bearing fruit, whereof if anyone tastes, he instantly dies. For these men are not the planting of the Father. For if they were, they would appear as branches of the cross, and their fruit would be incorruptible.

In the twelfth section, he again emphasizes obedience to the bishop, and asserts that the presbyters (priests) have an even greater duty to obey. Clearly, St. Ignatius takes for granted a specific hierarchical structure of Church authority in every local church. Honoring this hierarchy, he claims, is honoring to both the Apostles, and Christ (§12):

Continue in harmony among yourselves, and in prayer with one another; for it becomes every one of you, and especially the presbyters, to refresh the bishop, to the honor of the Father, of Jesus Christ, and of the apostles. I entreat you in love to hear me, that I may not, by having written, be a testimony against you. And do you also pray for me, who have need of your love, along with the mercy of God, that I may be worthy of the lot for which I am destined, and that I may not be found reprobate.

In his farewell in the thirteenth section, he makes one final mention of obedience and again connects it with maintaining the unity of the Church (§13):

Fare you well in Jesus Christ, while you continue subject to the bishop, as to the command [of God], and in like manner to the presbytery. And do you, every man, love one another with an undivided heart.

In this brief letter, like the others, we see the following about St. Ignatius:

- He had a high view of Church authority;

- He considered obedience to the hierarchical structure of bishops, priests, and deacons to be obedience to Christ;

- He believed that this obedience is intrinsically linked to Eucharistic communion around the Christian altar; and

- He believed obedience to these ministers provided strong protection against falling into heresy.

Letter to the Smyrnaeans

We’ll end Part 1 of this series by examining St. Ignatius’s Letter to the Smyrnaeans, which was one of the most shocking and “red pilling” of all his letters that I read, primarily because of the manner in which he describes the Eucharist (the most explicit of all his letters), and his use of the term “Catholic Church.” He wrote two letters to the Church in Smyrna: this first one, apparently intended to be read to the whole church; and a second, sent privately to St. Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna. We will cover the first one here, and the personal letter to St. Polycarp in Part 2.

Near the beginning of his letter to the church in Smyrna, St. Ignatius describes the outlines of Christian belief about Christ’s Incarnation in a way that is very similar to the Apostles’ Creed, and speaks of the Christian vocation to come into “the one body of His Church” (§1):

I have observed that you are perfected in an immovable faith, as if you were nailed to the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, both in the flesh and in the spirit, and are established in love through the blood of Christ, being fully persuaded with respect to our Lord, that He was truly of the seed of David according to the flesh, and the Son of God according to the will and power of God; that He was truly born of a virgin, was baptized by John, in order that all righteousness might be fulfilled by Him; and was truly, under Pontius Pilate and Herod the tetrarch, nailed [to the cross] for us in His flesh. Of this fruit we are by His divinely-blessed passion, that He might set up a standard for all ages, through His resurrection, to all His holy and faithful [followers], whether among Jews or Gentiles, in the one body of His Church.

In section 4, he then expounds on the fact that Christ possessed a true body, contrary to heretics, like the Docetists, who claimed he was just a spirit. He warns the Smyrnaeans to avoid them, calling them “beasts” (§4):

I give you these instructions, beloved, assured that you also hold the same opinions [as I do]. But I guard you beforehand from those beasts in the shape of men, whom you must not only not receive, but, if it be possible, not even meet with; only you must pray to God for them, if by any means they may be brought to repentance, which, however, will be very difficult.

He goes on to describe these heretics as “the advocates of death rather than of the truth” (§5).

In section 6, he goes on to affirm that heresy stems from pride, and a lack of love for the Church, which felt ominously familiar to me as a protestant, given his many other statements about authority and unity (§6):

Let no man deceive himself. Both the things which are in heaven, and the glorious angels, and rulers, both visible and invisible, if they believe not in the blood of Christ, shall, in consequence, incur condemnation. “He that is able to receive it, let him receive it” (Matt. 19:12). Let not [high] place puff anyone up: for that which is worth all is faith and love, to which nothing is to be preferred. But consider those who are of a different opinion with respect to the grace of Christ which has come to us, how opposed they are to the will of God. They have no regard for love; no care for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; of the bond, or of the free; of the hungry, or of the thirsty.

Section 7 was earth-shattering for me, for in it, St. Ignatius affirms not only the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist, but in such a way that his meaning could only be Catholic (§7):

They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer [some read “offering”], because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again. Those, therefore, who speak against this gift of God, incur death in the midst of their disputes. But it were better for them to treat it with respect, that they also might rise again. It is fitting, therefore, that you should keep aloof from such persons, and not to speak of them either in private or in public, but to give heed to the prophets, and above all, to the Gospel, in which the passion [of Christ] has been revealed to us, and the resurrection has been fully proved. But avoid all divisions, as the beginning of evils.

Observe that St. Ignatius affirms the reality of the real presence by identifying the Eucharist with the same flesh and blood of Christ that died and rose again. The real presence he speaks of is thus not symbolic, or even “merely” spiritual, but substantive, meaning, it is in some sense physical. St. Ignatius grounded the reality of the Eucharist on the reality of Christ’s physical body. This notion of the Eucharist didn’t fit any protestant conception, including even the “high church” varieties among Calvinists, Lutherans, and Anglicans. I know some of them would dispute this, but I found, and continue to find, their arguments, and the language of their historic creeds and confessions, flatly contradictory to the plain and direct language of St. Ignatius, which can be read in any Catholic Church to this day without qualification.

I was frequently told this view of the Eucharist was a medieval invention that came centuries, if not millennia after Christ. But here it was, not even 100 years after the Ascension, from the mouth of a companion of the Apostles, ordained by their hands, and a martyr for the faith. Once more, my basic framework of normative Christianity was shattered.

It was also very eerie to me, while still protestant, to read him warn that those “who speak against this gift of God, incur death in the midst of their disputes.” This seemed to perfectly describe what we protestants had been doing since the 16th century: we had denied this gift of God, and had likewise been disputing amongst ourselves about the very thing we denied. It naturally followed from St. Ignatius’s words that we had thereby undergone some form of spiritual death.

All the protestant tomes in the world seeking to explain their contradictory views of the Eucharist could not do as much as these simple, direct, unvarnished words from a companion of the Apostles.

In section 8, St. Ignatius once more affirms the necessity of obeying the bishop as the solution to avoiding heresy, and again references the three-fold offices of bishop, priest, and deacon. For him, the unity of the Church flows from the Eucharist, and neither the Eucharist, nor baptism, nor any other matter should be administered without the bishop. And for the first time in the documentary record of the Church, he refers explicitly to the name of the one true Church as the “Catholic Church” (§8):

See that you all follow the bishop, even as Jesus Christ does the Father, and the presbytery as you would the apostles; and reverence the deacons, as being the institution [command] of God. Let no man do anything connected with the Church without the bishop. Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist, which is [administered] either by the bishop, or by one to whom he has entrusted it. Wherever the bishop shall appear, there let the multitude [of the people] also be; even as, wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful without the bishop either to baptize or to celebrate a love-feast; but whatsoever he shall approve of, that is also pleasing to God, so that everything that is done may be secure and valid.

For St. Ignatius, it is perfectly clear that the bishop is the center of authority, unity, and worship (i.e. the Eucharist). Note his extraordinary language comparing the obedience of Christ toward the Father, and of Christians toward the Apostles, with the obedience Christians owe to the bishops and priests. This was not a Church making things up because it had been corrupted by power, wealth, and glory (which is what I had heard most of my life). This was the structure of authority in the Catholic Church even under intense persecution not even a century after Christ’s Ascension—the same basic structure the Church has today.

St. Ignatius then declares in section 9 that by dishonoring the bishop, one serves the devil (§9):

Moreover, it is in accordance with reason that we should return to soberness [of conduct], and, while yet we have opportunity, exercise repentance towards God. It is well to reverence both God and the bishop. He who honors the bishop has been honored by God; he who does anything without the knowledge of the bishop, does [in reality] serve the devil.

Near the end, in section 12, he again salutes the priesthood of the church in Smyrna, and once more references their union in the flesh and blood of Christ, which is undoubtedly connected to his previous words about the Eucharist (§12):

I salute your most worthy bishop, and your very venerable presbytery, and your deacons, my fellow-servants, and all of you individually, as well as generally, in the name of Jesus Christ, and in His flesh and blood, in His passion and resurrection, both corporeal and spiritual, in union with God and you. Grace, mercy, peace, and patience, be with you forevermore!

Note that, just as in other letters, St. Ignatius again appeals to the unity of Christ’s flesh and spirit. To claim to be separated from the one body of Christ in the name of some spiritual good was, for him, inconceivable. The visible Church is what Christ had established forever.

We can thus see in this letter all that St. Ignatius has mentioned elsewhere, except more explicitly with respect to the Eucharist, and the particular name of the one true Church founded by Jesus Christ: the Catholic Church.